Hollier may struggle with 13th District ballot due to petition signature issue | Opinion

This is going to be complicated, and fair warning, it involves a lot of talk about nominating petitions and signature gatherers and various boards of canvassers, which seems like the text equivalent of Ambien.

But if you stick with me, we'll get to the part where a congressional campaign forged a Free Press reporter's signature on a nominating petition, and a host of other signature problems alleged by a sitting congressman — who is also seeking to have top state election officials' name struck from those petitions — and the implications all of this has for an important Detroit congressional race.

The petitions in question belong to Adam Hollier, a former state senator who is seeking to unseat incumbent U.S Rep. Shri Thanedar, elected in 2022 to represent Michigan's 13th District.

Thanedar is asking the Wayne County Clerk to disqualify his opponent from the August primary ballot, saying that just 764 of the 1,555 signatures submitted by Hollier are valid.

Most of the problems identified by Mark Grebner of Practical Political Consulting, the state's leading voter data expert, fall into a few categories: duplicated signatures, signers who aren't registered to vote or are registered to vote at a different address than the one written on the petition, signers who live outside the 13th District, or who haven't properly listed their cities of residence, or pages lacking adequate documentation by the petition circulator.

Eighty-five signatures, the analysis alleges, were simply forged.

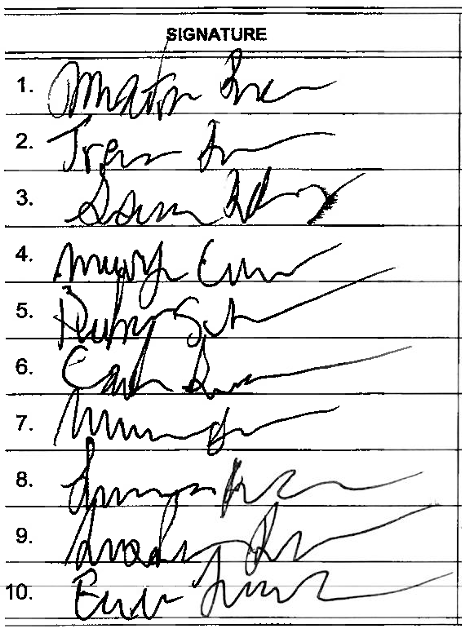

I generally try to stay in my lane, and I'm a columnist, not a handwriting analyst. But it's hard to look at the signatures on nine of 10 petition pages provided to the Free Press by Thanedar and not conclude that they'd been written by the same person; that they're forgeries, and not very good ones, at that.

"If you can see that it was forged while holding it at arm’s length, it’s not a good forgery," Grebner said.

And that was before one name in particular popped out: My Free Press colleague, courts reporter Tresa Baldas.

When I called Baldas, she was floored. She confirmed that the petition bore her full name, Tresevgene Baldas, and her east side address — and that she hadn't signed it.

"I'm a reporter, I can't sign petitions," Baldas said. "That's not my signature.”

All of the pages bearing apparent forgeries were signed by petition circulator Londell Thomas, who didn't reply to an email sent to an address listed on the website of his business, Groundmind Strategies. When I called the number listed on the Groundmind website, the man who answered said he was not Thomas, then hung up after I explained why I was calling.

Forging petition signatures is a misdemeanor.

Hollier told me Wednesday that he had not personally reviewed all of the petition signatures, but that he was confident his campaign would survive the challenge and that his name would appear on the primary ballot.

His campaign sent this statement after I discovered Baldas' name on the petition pages: “Some issues have been brought to our attention related to a small number of the nomination signatures that were collected on behalf of our campaign. We have retained legal counsel to look into the matter, and are confident that a significant number of the challenges filed against our signatures are erroneous.”

How all of this works

In Michigan, candidates for office must convince a designated number of registered voters — for this race, a thousand — to sign nominating petitions. Campaigns often outsource this job, hiring a professional who can deploy a team of signature gatherers. You've probably run across those folks this time of year, holding clipboards and asking you to support a candidate or cause — I always see them on Saturdays at Eastern Market. Most candidates try to get more signatures than required, in case some don't hold up.

After the filing deadline, April 23 this year, state or county elections staff work to verify the signatures or flag potential problems. Competing campaigns also pore over their opponents' petitions, looking for grounds to disqualify.

Some candidates have seen their political careers truncated by fraud — that's how former Detroit Police Chief James Craig's 2022 run for the GOP gubernatorial nomination was derailed, and how former U.S. Rep. Thad McCotter, also a Republican, lost his seat. It's normal for a certain number of signatures to be disqualified, for mundane reasons: The signer may not live in the right district, or may not be registered to vote, so campaigns generally work to supply surplus signatures.

Some of the questionable signatures — the ones with incorrect addresses, for example — can be rehabilitated, said election law expert Mark Brewer, if Hollier's campaign can defend their inclusion.

Hollier must respond to Thanedar's challenge by next week. The Wayne County Clerk's staff will prepare a report detailing the challenges and any additional information for each signature.

The Wayne County election commission will decide whether Hollier's name will appear on the ballot.

Either candidate can appeal the board's decision to the Wayne County Circuit Court. All of this takes time, and the question of Hollier's candidacy may not be resolved until early June. Absentee ballots go out June 27. The election is Aug. 6.

1 more thing

Some of the signatures Thanedar is challenging are marked as another category: "Fradulent canvasser, please disqualify" — in other words, Thanedar is also asking the Wayne County Board of Canvassers to disqualify any signature obtained by Thomas, a category that includes Michigan Secretary of State Jocelyn Benson — the state's chief election officer — and Mary Ellen Gurewitz, chair of the state Board of Canvassers. Benson is one of many elected officials who've endorsed Hollier this cycle.

(Benson's office sent this statement: "As a registered voter and resident of the 13th District, Secretary Benson is eligible to sign candidate nominating petitions.")

Because the entire 13th Congressional District is contained within Wayne County, it's the county board and clerk who will decide the fate of Hollier's candidacy, not the state, so there is no apparent conflict of interest. But it doesn't make the situation less odd.

What this means for the 13th District

Michigan's 13th Congressional District is a complicated seat.

U.S. Rep. Brenda Lawrence's 2022 retirement spawned a free-for-all, with nine candidates seeking the office. Because it's such a strongly Democratic district, this race is decided in the primary, when few voters turn out, and all kinds of wacky things can happen — like the vote splitting nine ways in a low-turnout election, sending a candidate most voters didn't choose to the U.S. Congress.

That would be Thanedar.

Thanedar hasn't won many friends in political circles. He'd previously run, unsuccessfully, for governor in 2018, and won a state House seat in 2020. Largely self-funded, he spends copiously.

There are currently no Black federal elected officials representing the city of Detroit in Washington D.C., and some Detroiters feel strongly that the city should have Black representation — in 2022, Wayne County Executive Warren Evans convened a group of civic and political leaders to coalesce support around Hollier, with the stated purpose of keeping Thanedar from winning. It did not work.

Thanedar hasn't won rave reviews as a congressman; fellow U.S. Rep. Rashida Tlaib, another Detroit Democrat, called Thanedar out last year for poor constituent services. (Since then, a host of billboards touting Thanedar's accessibility have sprouted in metro Detroit.)

Hollier has won the endorsement of dozens of Michigan elected officials, but Thanedar has retained the fundraising advantage, due largely to his own wealth and an unconventional investment in Bitcoin.

And Detroiters vote for Thanedar. He lost statewide, but was the top vote-getter in Detroit in the 2018 gubernatorial primary, besting Gov. Gretchen Whitmer a few thousand votes.

In a way, this is a cautionary tale about — well, elections, I supposed. Holding office is hard work. So is running for it. Elections are full of variables, and although outcomes can seem foreordained, really, anything can happen.

Hollier may be able to rehabilitate a sufficient number of the signatures Thanedar is challenging to stay on the ballot. It may be harder to rehabilitate his campaign.

Nancy Kaffer is editorial page editor of the Detroit Free Press. You can contact her at nkaffer@freepress.com. Submit a letter to the editor at freep.com/letters, and we may publish it online or in print.

This article originally appeared on Detroit Free Press: Signatures submitted by Adam Hollier not valid, Shri Thanedar says