Hogtying is banned in much of WA state. Why is Pierce County’s sheriff OK with the risk?

The Pierce County Sheriff’s Department continues to allow deputies to connect detainees’ handcuffs to leg restraints behind their backs – also known as hogtying and maximum restraint – despite the practice’s safety risks and recent moves to curb its use across the state and country.

The technique – which records show Tacoma police and a Pierce County sergeant employed to restrain Manuel Ellis face-down for several minutes before he died of oxygen deprivation nearly three years ago – is now prohibited in Tacoma, Puyallup and several other Pierce County cities. The sheriff’s offices for King and Spokane counties also have bans on hogtying, as does the Seattle Police Department.

The Sheriff’s Department made its case in favor of hogtying in December in response to the state Attorney General’s Office’s recently created model use-of-force policy.

A 2021 statutory reform required each police agency in the state to enact a policy consistent with the Attorney General’s model policy by the end of the year. Those that did not were required to submit an explanation as to why they declined to do so and how their policy complies with lesser state laws. Statewide, only the Pierce County Sheriff’s Department submitted a memo to the Attorney General strongly defending the safety of hogtying.

“There is no statute that prohibits its use. Provided the individual is monitored and placed in proper position after application of the restraint, the restraint can be safely used,” according to a memo from the Sheriff’s Department to the Attorney General. “The 4 point restraint in and of itself has not been proven to cause death.”

Typically used by police to restrain combative detainees, hogtying involves multiple officers holding a handcuffed detainee on their stomach, tightening an adjustable “hobble” cord around their ankles and hooking the cord to the handcuffs. Some agencies, such as the Sheriff’s Department, advise against cinching the restraints to bend the detainees’ legs farther than 90 degrees.

Washington’s Basic Law Enforcement Academy doesn’t train new officers to use hobbles or other leg restraints, according to a spokesperson.

Sheriff’s Department spokesperson Sgt. Darren Moss said all Pierce County deputies receive that training in-house.

To avoid restricting a hogtied person’s breathing to the point of death, commonly known as positional or restraint asphyxia, the Sheriff’s Department advises deputies to immediately remove pressure from the restrained person, roll them onto their sides and continuously monitor them, according to Moss.

“You need to get off the person. That’s the key,” Moss said. “That’s the big difference with a lot of these (in-custody death) situations. ... That’s how people get hurt.”

The Sheriff’s Department’s hogtying policy also instructs deputies not to leave detainees in a prone position, and has done so since at least November 2020, according to a copy on the county’s website. The updated policy from December includes a new exception that if a detainee rolls onto their stomach, deputies are advised against “fighting them into a different position” to prevent injury to the deputy or detained person.

In the memo defending hogtying and other differences with the Attorney General’s model, the Sheriff’s Department cited medical research included in a 1998 federal court decision. That study by a group of physicians — partially paid for by San Diego County amid a wrongful death lawsuit — determined hogtying 15 healthy volunteers face-down reduced their breathing capacities by up to 23%. The researchers, who The New York Times reported became paid experts to defend police in court, opined the impact wasn’t “clinically relevant.”

The research and advocacy organization Physicians for Human Rights has found research on hogtying — including the San Diego study— is limited by small sample sizes of mostly healthy people and does not accurately replicate police forcibly restraining people during a struggle, which can involve intoxication and mental illness.

The Sheriff’s Department memo to the Attorney General’s Office also said the department declined to ban baton strikes on a person’s groin or kidneys, unless deadly force is authorized, because a “baton strike to those regions is not likely to cause death or serious physical injury.” Numerous agencies around the country prohibit similar strikes outside deadly force situations, frequently noting the potential for serious injury.

Because Sheriff Ed Troyer is an elected official, his department has sole authority to initiate revisions to its use-of-force policy.

“We really need to ask the elected sheriff about the use-of-force policy,” said recently elected County Council Chair Ryan Mello, a Democrat who argued in 2021 that an appointed sheriff could be held more directly accountable, like a police chief who answers to a city council or city manager.

“Hogtying is incredibly dehumanizing,” Mello said during a phone interview. “The people of Pierce County have every reason to give input and question how they’re being policed.”

Washington’s model use-of-force policy

The Attorney General’s Office published its model use-of-force policy for law enforcement in July. More than a dozen agencies have not yet responded with their own policies despite a Dec. 1 deadline to submit them. About two dozen departments said their policies had inconsistencies with the Attorney General’s model, including a requirement that officers fire tasers with their weakside hands outside extreme circumstances.

Agencies are required to resubmit their policies again at the end of each year or upon any changes. State law did not prescribe penalties for noncompliance.

Some Pierce County agencies didn’t address hogtying or restraints in their use-of-force policies, though force is defined under state law as any restraint beyond painless, compliant handcuffing. The Lakewood Police Department continues to allow hogtying in a separate policy section but reported its use-of-force policy is consistent with the Attorney General’s model.

The Enumclaw Police Department wrote to the Attorney General’s Office that it did not ban hogtying “as this deviates from our existing training, techniques and tools currently utilized to safely restrain a subject from harming themselves or others.”

The Washington Coalition for Police Accountability, which was formed following advocacy for the state law mandating independent deadly force investigations, is against hogtying and has backed the Attorney General’s model policy.

“Local agencies who still train on and use hogtying are out of touch with the duty to preserve life, the duty of reasonable care, and the extreme risk inherent in that tactic,” spokesperson Leslie Cushman said in an email.

Pierce County Sheriff’s Department use-of-force data for 2016 through 2021 showed deputies reported using hobble restraints about 60 times a year. Deputies used hobbles on Black people, who make up about 4.8% of the Sheriff Department’s service population, in about 28% of those cases, or 62 times.

The same report found Black people experienced more than five times as much force as white people in Pierce County. Native American or Alaska Native people experienced about 3.6 times as much force as white people.

The Sheriff’s Department provides policing services for the cities of Edgewood and University Place under contracts; they also frequently respond to incidents in conjunction with Tacoma police, which was the case during the in-custody death of Ellis in March 2020.

Hobbles used to restrain Ellis

At the time of Ellis’ death, the Tacoma Police Department did not issue hobbles to officers and its policy manual was nearly silent on leg restraints, according to the department’s internal investigation. A section on transporting detainees advised, “Arrestees will not be transported in a ‘hog-tied’ position or face down.” The use-of-force policy does not mention hobbles.

After officers Matthew Collins and Christopher “Shane” Burbank hit, choked and used a Taser on Ellis to get him in handcuffs on March 3, 2020, backup officers Timothy Rankine and Masyih Ford arrived to restrain Ellis from struggling on the ground, according to investigative documents. Rankine sat on Ellis’ back while Burbank grabbed Collins’ hobble from a patrol car.

Ford and Collins held Ellis’ legs as Burbank looped the hobble cord around Ellis’ ankles, according to investigative documents. Pierce County Det. Sgt. Gary Sanders helped put one of Ellis’ feet in the hobble before Tacoma officers cinched down the cord.

Moments after Ellis was hogtied, Ford told investigators, Ellis reported he couldn’t breathe, and officers rolled him onto his side in the “recovery position,” documents show. Rankine said in his interview with Sheriff’s Department detectives that Ellis began struggling with officers on his side so he told them to roll Ellis back onto his stomach and reapply pressure.

At some point, a fifth Tacoma officer, Armando Farinas, put a spit hood over Ellis’ head, according to a Tacoma Police Department summary of his involvement. He told investigators he was never aware of Ellis having trouble breathing.

Ellis remained on his stomach with officers on top of him for several minutes before police transitioned him back into the recovery position as medical personnel arrived, according to investigative documents. Ellis was unresponsive by the time medical aid began.

Sheriff’s Department detectives did not ask Collins, nor his partner Burbank, how they obtained the hobble stored in their patrol car, according to investigative documents. After removing the hobble from Ellis, Burbank told detectives he put it back in the glove box.

After three months of investigating, the Sheriff’s Department disclosed for the first time that its own deputies were at the scene when Ellis died. Gov. Jay Inslee ordered a new investigation by the Washington State Patrol and gave Attorney General Bob Ferguson’s office the authority to prosecute the case.

The Attorney General’s Office charged Burbank and Collins with second-degree murder and Rankine with first-degree manslaughter in May 2021. Sanders, Ford and Farinas were neither charged nor disciplined by their respective agencies.

Charging documents state the Medical Examiner’s autopsy initially determined Ellis died from a lack of oxygen due to the way he was restrained and cited the spit hood, methamphetamine in his system and a heart condition as significant contributors to his death.

After reviewing additional evidence, former Medical Examiner Dr. Thomas Clark, who is now retired, reaffirmed his finding that Ellis died from officers restraining him, according to charging documents.

At the time of the autopsy, Clark wasn’t aware of the amount of pressure put on Ellis’ back, which could have contributed to his death, according to charging documents. Heart monitor readings showed Ellis’ heart rate was slow and that he deteriorated gradually, which Clark opined was inconsistent with death from methamphetamine intoxication or a sudden cardiac episode.

Sanders and Pierce County Lt. Anthony Messineo, who was on-scene but did not touch Ellis, both told investigators they didn’t see any issues with how Tacoma police restrained him.

“I witnessed nothing inappropriate. No force being used other than detaining the subject,” Messineo told a Sheriff’s Department detective and an investigator from the Prosecuting Attorney’s Office in an interview. “There was no strikes. There was, there was nothing.”

Last year, Pierce County agreed to pay the Ellis family $4 million to settle part of a federal wrongful death lawsuit. The agreement also dismissed Sanders as a defendant. Claims against the city of Tacoma and the city police officers charged in Ellis’ death are pending the conclusion of their criminal trial scheduled for September.

Hogtying alternatives

Other departments around the state, such as the Tacoma Police Department, adopted the Attorney General’s model wholesale. The model policy allows officers to bind a detainee’s feet with a hobble cord so long as they don’t connect it to other restraints and report it to a supervisor.

Moss, the sheriff’s department spokesperson, said banning hogtying for Pierce County deputies would leave them without a tool to immobilize and de-escalate people who are handcuffed but continue to kick at deputies or their patrol cars once inside. Moss said if the hobble isn’t attached to handcuffs, a deputy has to hold the other end of the strap and could be kicked.

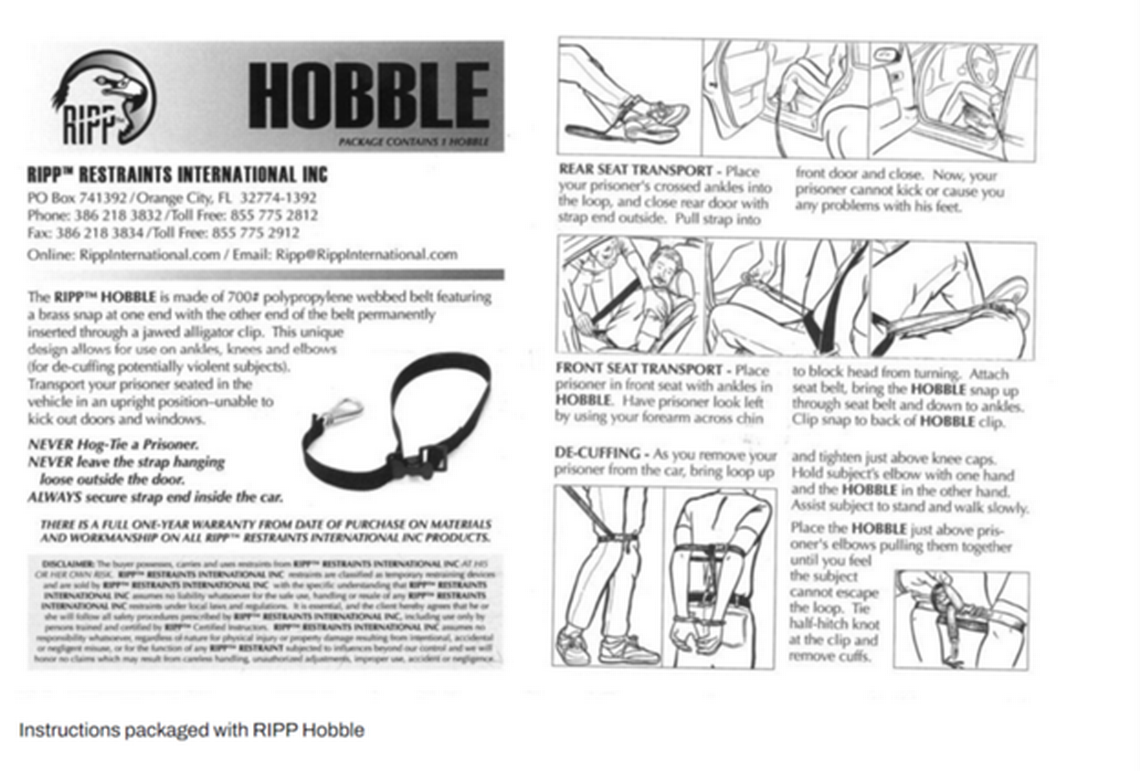

Instructions for the RIPP Hobble purchased by many police departments warn against hogtying and show that officers can prevent kicking damage to patrol cars by closing the door on the end of the hobble strap. Moss told The News Tribune he was issued a similar hobble manufactured by Don Hume.

The police chief for the small city of Algona in south King County, James Schrimpsher, told The News Tribune his policy was already more restrictive than the Attorney General’s model: He doesn’t allow officers to carry a hobble at all.

“Just in my 27 years, hogtying to me is nothing I’m interested in,” said Schrimpsher, a former King County deputy.

Schrimpsher said the seven officers in his department — most of whom are early in their careers — are instructed to call emergency medical services to help subdue combative detainees by restraining them on a gurney.

“If they’re in handcuffs and they’re in the back of a patrol car,” Schrimpsher said, “is there a harm from them kicking on metal bars?”

Schrimpsher said the several hundred dollars to replace a car door is better than the alternatives: injury or death that can lead to costly lawsuits.

Last month, San Diego County agreed to pay $12 million to the family of a man who died after deputies beat, shocked him with a stun gun and hogtied him in 2015, according to The New York Times.

Mike Blair, a former police chief in University Place and chief of staff under former Sheriff Paul Pastor, told The News Tribune that he’s in favor of expanding the use of sedatives, such as ketamine, as an alternative to hogtying. He said Schrimpsher’s method of calling in paramedics isn’t practical for the size of Pierce County.

“Hogtying is a thing of the past,” said Blair, who most recently worked as a patrol sergeant before retiring last year.

Blair said the deputies he oversaw got into dangerous struggles with detainees nearly every night and estimated they asked paramedics to sedate someone once a week. Sedated detainees are then transported to the hospital to wake up.

Ketamine sedation also has its dangers and detractors.

Elijah McClain, a 23-year-old Black man, died in the hospital after Aurora, Colorado, police used a chokehold on him and paramedics sedated him in 2019. Last fall, the medical examiner changed the previously undetermined cause of McClain’s death to the lethal dose of ketamine he received, according to NPR.

In 2020, the American Society of Anesthesiologists and American College of Emergency Physicians announced their opposition to law enforcement using ketamine or other sedatives to chemically incapacitate people for non-medical purposes.

The West Richland Police Department in the Tri-Cities told the Attorney General’s Office it uses the WRAP system as an alternative to supplying officers with hobbles.

A full-body harness that wraps a person’s legs together and straps their upper body into a seated position, the WRAP has also been cited as contributing to in-custody law enforcement deaths when deployed improperly. The San Diego Union-Tribune reported that about 900 agencies in the United States were using the device in 2018.

Who could weigh in on Pierce Sheriff’s policy?

Following an inquiry by The News Tribune, Mello, the County Council chair, said he reached out to Sheriff’s Department command staff to learn more about the hogtying policy and whether it risked harm to citizens or liability to the county.

“They’ve assured me that they only use it when absolutely necessary,” Mello told The News Tribune during a phone interview. He added later, “Using it does give me concern.”

The Sheriff’s Department is gathering statistics about hogtying usage and attested that deputies have not reported harming anyone with hobble restraints during the past three years, according to Mello.

Mello said the county is in the early stages of engaging stakeholder groups about forming a civilian oversight entity, which might weigh in on department policies.

Tacoma Human Rights Commission member Andre Jimenez worked on the one-year Pierce County Equity Review Committee, which made recommendations on county diversity and criminal justice initiatives. Jimenez said the county should create a permanent equity commission, which the Equity Review Committee voted to do before it was disbanded last year.

The County Council created the committee in August 2021 to review County Executive Bruce Dammeier’s recommendations for developing a county equity index and tools for assessing cultural competency in county operations. The committee also reviewed findings from Dammeier’s Criminal Justice Workgroup but did not specifically examine the Sheriff’s Department use-of-force policy.

“This is a perfect example where an equity commission could step in and say something,” said Jimenez, who criticized how often the Sheriff’s Department’s deputies use force in an op-ed for The News Tribune last year.

Jimenez told The News Tribune the Sheriff’s Department’s stance on hogtying reflects a disregard for the community’s wishes given the circumstances of Ellis’ killing. He said the department should prioritize rebuilding trust with the community and identifying new public safety solutions.

“I think the AG set a model bare-floor minimum, and again Pierce County failed to meet the mark,” Jimenez said.