The Hidden Cycling Injury That’s Forcing Women to Give Up Riding Bikes

When Caroline Worrall discovered cycling at the age of 40, it was like discovering a superpower. On group rides, she was faster than others to the point where she sometimes wondered why everyone else was going so slow. Riding flat pedals on one of her early outings, she beat a group of men in a sprint. About five years in, after she’d progressed to regular 50- to 60-mile rides, she began to notice pain and swelling in her labia that forced her off the bike for stretches of time, even as long as a month. She tried at least 30 saddles over the course of a decade—none helped. Meanwhile the tissue grew thicker until she could no longer wear padded shorts on long rides. She briefly contemplated surgery. She rode mostly with men in Gainesville, Florida, where she lived. She had no one to talk to about it.

In 2009, Jacqueline McClure, then 26, got on her mom’s old steel Panasonic with down-tube shifters and rode 100 miles on California’s Highway 1. Her first elite racing team gave her a men’s Specialized S-Works saddle, which she rode for almost two seasons even though she was plagued by sores. She eventually switched saddles, but her problems persisted—and the sores progressed to permanent swelling on one side. When she told bike fitters, who were almost always men, they stared at her wide-eyed. Once a gynecologist asked, “What happened to you?” She responded, “I ride a bike all day.” Now 40, McClure hasn’t raced for three years, and rides much less than before, but until recently her labia remained lopsided. “As a woman,” she says, “it makes you feel a little damaged.”

Like many Americans, Hannah Knapp, 29, started cycling during the pandemic. She loved it immediately, but she could never ride more than 10 miles on her hardtail mountain bike before saddle pain overwhelmed her. Longtime female cyclists told her this was normal, that she’d get used to it. But six months later it still hurt. When her boyfriend noticed how much chamois cream she was using, he took her to a fitter. It turned out she was on a saddle that was two inches too narrow for her sit bones. Switching it out enabled her to double her mileage immediately, but damage had been done. Soon she developed a hard, excruciating lump on the left side of her groin. Her doctor didn’t believe it was from cycling and prescribed oral antibiotics. When that didn’t work, Knapp finally found a dermatologist who had seen lumps like this among triathletes. He cut out a mass that fit in the palm of her hand. At her follow-up visit, she cried tears of relief. She could ride a bike now. She wasn’t crazy.

In 2019, Specialized released what was then a revolutionary new women’s saddle technology. They called it Mimic because it was designed to increase comfort by matching saddle density to the rider’s contact points. The press coverage kicked off a long-overdue conversation about women’s saddle issues and aired one of pro cycling’s open secrets: that some women suffer so much damage to their genital areas they resort to surgery—labiaplasty—to keep riding.

But the conversation was short-lived. Names of pros who have had surgery are only whispered among the peloton, while amateurs desperate for solutions find little practical advice. Many push through the pain, riding their way toward long-term damage.

Join Bicycling for unlimited access to best-in-class storytelling, exhaustive gear reviews, and expert training advice that will make you a better cyclist.

It’s a remarkable level of reticence around a problem that likely plagues a large portion of female cyclists. On one UCI Women’s WorldTour team, half the women had considered or undergone labial surgery, or had labial disfigurement that forced them to sit on their bike differently, says Andrew Pruitt, EdD, expert bike fitter and founder of the Boulder Center for Sports Medicine. A 2016 survey of 114 Dutch cyclists found that 35 percent reported vulval swelling.

In 2023, Bicycling conducted its own survey. The results were startling: Nearly 50 percent of the female respondents told us they had long-term genital swelling or disfigurement, while 16 percent experienced ongoing numbness. Twelve of the 89 respondents—all amateurs but one—said their issues were serious enough to consider or undergo surgery. Women shared that they often rode in pain, cut rides short, or had to take long breaks from the bike.

An untold number of women have almost certainly left the sport due to saddle discomfort. If we had a way to survey that subset, “I’m absolutely convinced the numbers would be huge,” says Phil Burt, an expert bike fitter in Manchester, England, founding member of Team Sky, and former Olympic team physiotherapist for British Cycling.

Back in 1997, Bicycling published a story that linked cycling to erectile dysfunction in men. The article sparked a slew of research on the sport’s impact on male sexual health and led to the development of the first Specialized Body Geometry saddle, which featured a center cutout that relieved arterial pressure. “That story brought it out of the closet,” says Pruitt, who was also a consultant for Specialized’s Body Geometry line and lead developer of the Mimic. But for women, he says, it’s been “a silent epidemic.”

Bicycling recently spoke to doctors, researchers, bike fitters, and cyclists to demystify the debilitating pain and injuries women have been so reluctant to talk about. What emerged was not only a picture of what causes these conditions and how to prevent them, but also an argument for breaking the silence around women’s sexual health. For women, it turns out, silence and suffering go hand in hand.

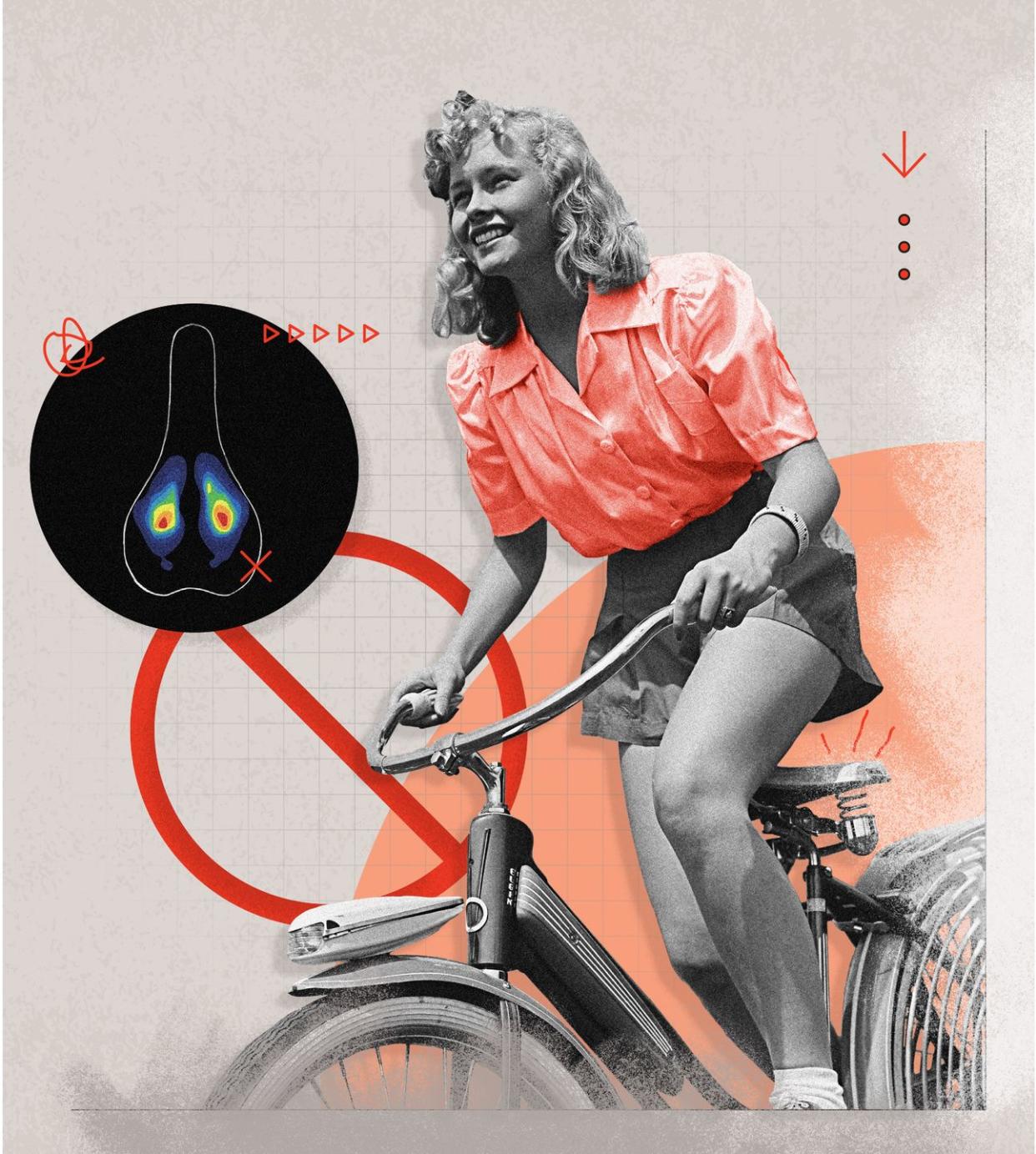

DURING THE BICYCLE boom of the 1890s, the idea of women riding was controversial, and the debate centered on women’s reproductive health. Some doctors claimed that straddling a bicycle would corrode sexual purity, as contact with the saddle might cause arousal or even encourage masturbation. These pseudo-scientific arguments likely stemmed from an age-old fixation within sports science around the idea that exercise can harm women. “Throughout history, that’s been the narrative used to keep women out of sports—that exercise will ruin your reproductive system and you can’t have kids,” says Christine Yu, author of Up to Speed: The Groundbreaking Science of Women Athletes. “And God forbid you can’t have kids.”

But the docs weren’t totally clueless. As early as 1895, a researcher surmised that women could become numb while cycling (easing some fears of the bike saddle as an agent of arousal), while others warned that riding in the handlebar drops could cause harmful pressure on the front half of the genital area (a finding later verified by 21st-century science), resulting in painful “polypoid growth.” Despite this, women’s saddle issues are less researched than men’s, and fewer saddles are developed specifically for women, which could result in more injuries.

To fully understand what causes these injuries, it’s important to review some basic terms. Despite our colloquial use of the word “vagina,” the correct word for a woman’s external genitals is “vulva,” which includes the labia majora (fleshier outer lips), labia minora (inner lips), the clitoris, perineum, pubic mound, and the vaginal opening (but not the vagina, which is the muscular inner canal that connects the vulva to the uterus).

The consensus among doctors and experts is that long-term swelling of the labia (usually the labia majora) is a result of pressure, or crush, injuries. Genital tissue is rich in nerves, blood vessels, and lymph vessels—tiny, thin-walled, vein-like structures that drain the area of lymphatic fluid. Repeated, prolonged pressure can damage this neurovascular network, to various effects.

When the lymph vessels get crushed, they stop draining fluid, which causes persistent swelling. If blood vessels are crushed, they starve the area of blood, a process known as ischemia, which can eventually cause tissue to die. The body then attempts to heal by creating new tissue—essentially scar tissue—that’s thicker, drier, less elastic, and less efficient at exchanging blood and fluids. Over time, this process repeats until the flesh is permanently enlarged. The experts I spoke to agreed that the primary mechanism of vulval swelling among cyclists is lymphatic damage, exacerbated by the formation of scar tissue. (Swelling over the sit bones can also occur through a similar process.)

When plastic surgeon Heather Furnas, MD, began working with cyclists in her Northern California practice, most wanted treatment for the labia majora. Furnas was struck by the amount of pain the women had been tolerating on the bike. “I had never seen [labia] majora that big,” says Furnas, who is also a clinical associate professor of surgery at Stanford University. “And no cyclist had to tell me how traumatic it was. I could just see it.”

Crush injuries can also damage nerves. This can cause numbing or sometimes its opposite, hyperesthesia, meaning intense sensitivity. Cyclists who experience genital numbing are at increased risk of long-term sexual dysfunction, says Michael Eisenberg, MD, a professor of urology and ob-gyn at Stanford. Eisenberg, who has done research in this area and consults with a saddle company called VSEAT, says numbing generally serves as a warning sign that a rider’s saddle or fit could lead to other long-term issues, too, like soft-tissue damage.

Some women seek surgery on the labia minora when it causes painful pressure, chafing, or twisting. This happens most often when that tissue is bulky or hangs below the labia majora, but discomfort doesn’t always relate to size or length, Furnas says. Labia minora issues are primarily a matter of how our anatomy is built, and they can prevent women from sitting in a saddle, or in some cases even a chair, comfortably. One cyclist, who planned to undergo labiaplasty, told me she had to roll up her minora “like a cigarette” to ride without pain.

These long-term issues are different from saddle sores, which are caused by chafing or infection of a hair follicle. Saddle sores are generally short-lived and occur on or close to the surface of the skin. However, chronic repeated saddle sores can eventually lead to scarring, or even lumps that need to be surgically excised as the body consolidates swelling, says Phil Burt, the former British Cycling physiotherapist. Like numbing, repeated saddle sores are also an indication that you might be dealing with ongoing pressure issues that could lead to deeper injuries.

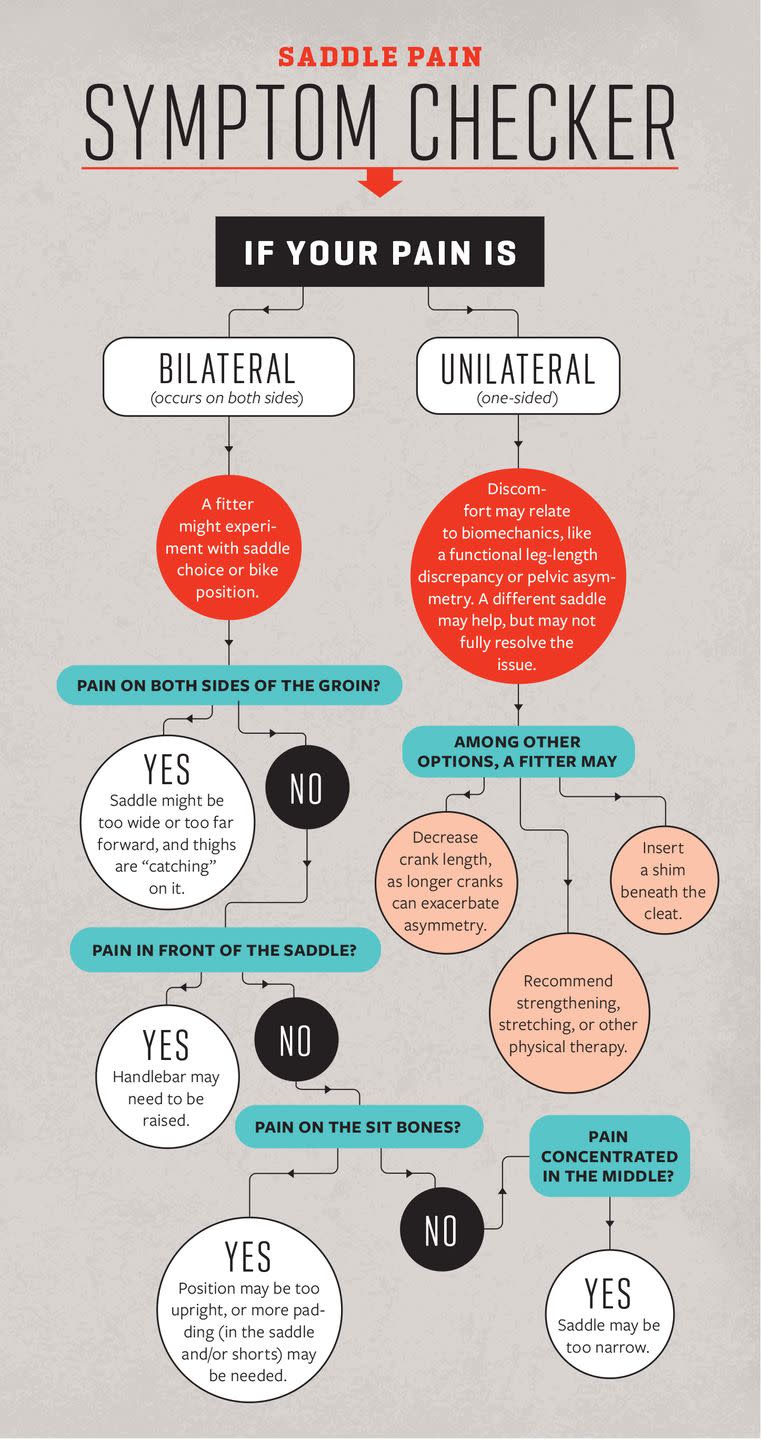

Saddle injuries can be the result of riding the wrong saddle (or the wrong size saddle) or having an incorrect bike fit. Women generally have wider sit bones, for example, and a saddle that’s too narrow can concentrate pressure on soft tissue. Correcting saddle width is often, Burt says, “one of those magical moments” in bike fitting. In extreme cases, one long ride on an ill-fitted saddle can cause permanent damage. But for the most part, these injuries happen slowly over time, the result of repeated microtraumas. This is why experts say it’s important to address saddle issues promptly, before surgery becomes the only recourse. “If you cycle 100 miles, you’ll get some saddle pain,” says Burt. “The problem is when you have an issue every time you get on a bike. That’s when you need to get help. It won’t get better on its own.”

IN 2007, AT the age of 22, a former collegiate tennis player named Alison Tetrick bought a road bike on eBay. In 2008, she did her first bike race, floundering with her clipless pedals at the start. By that summer, she was racing for the USA National Team and the powerhouse women’s pro squad, Team TIBCO.

Tetrick experienced extreme discomfort from the beginning. Her team-issue saddles were narrow and rigid, like most race saddles of the time, but when Tetrick told staff she was uncomfortable, she was told cycling was uncomfortable. Eager to succeed, she initially accepted the pain, as she saw others do, too. On the team bus during stage races, some women stuffed bags of ice or frozen vegetables down their shorts. Over time, the discomfort caused Tetrick to change her position on the bike, resulting in knee pain, and other chronic pain and inflammation issues. She was obligated to race on sponsor saddles, so she began to stipulate in her pro contracts that she could train on a saddle of her choice. Still, painful swelling in her labia progressed until one ride in 2015 when she had to reach into her shorts to manually adjust herself just to stay seated. Tetrick unclipped two miles from her house and turned to her riding partner. She was in pain. She was embarrassed. And finally, she was convinced this was not normal. “I can’t live like this,” she told him.

Tetrick decided to have surgery, which she had eventually learned from coaches and other riders was an option. But the prescriptive way this solution was presented—as if it were almost routine—angered her. “Like, you guys all knew?” she tells me now of her reaction. “What are we doing here? Let’s fix this problem.”

After her surgery in fall 2015, Tetrick shared her story with a female product manager from Specialized, who set up a meeting the following spring between her and two men from Specialized’s saddle team. The call took place in the evening for Tetrick, who was racing in Europe, and she was so uncomfortable discussing her saddle issues that she poured herself a drink to get through it. During the discussion, someone wondered whether Tetrick’s problems were perhaps unique. She informed them that, in fact, she knew some Specialized-sponsored female athletes who were resorting to surgery to address pain and disfigurement. The team was surprised. They set up more meetings. And the Mimic project was born.

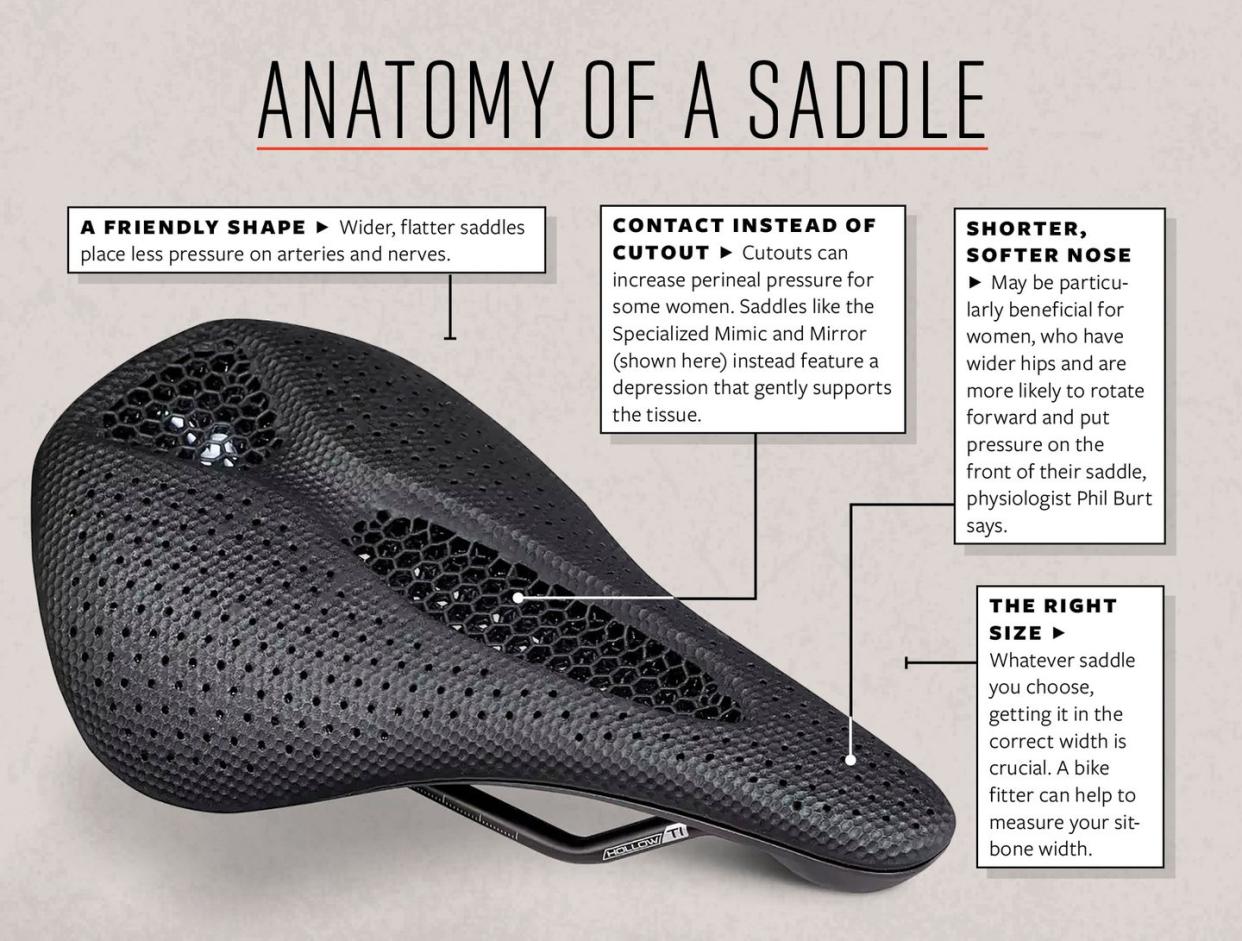

The development process for the Mimic busted long-held beliefs about women’s saddles, which for years had borrowed cutout technology from men’s versions. A team led by Pruitt recruited more than 20 women volunteers, including Tetrick, and had them pedal on clear plastic saddles in various situations—nude from the waist down, wearing padded and unpadded bike shorts, and wearing unpadded Spanx. Using visual observations and pressure-mapping technology, Pruitt concluded that rather than decreasing pressure, as previously believed, cutouts actually engulfed the flesh and caused the labia to swell into the hollow, increasing pressure sharply from one area to another.

Pruitt is an amputee; he knew from his experience with how prosthetics are fit to residual limbs that he needed to distribute pressure as evenly as possible between saddle and rider, by mimicking the softness of the tissue that contacts each area. The team constructed a prototype made of four unique pieces of foam, each with different densities. Softer foam in the nose relieved higher pressures in the front, while denser foam around the rear supported the sit bones. The former cutout became a depression with a layer of foam that supported the flesh like a hammock, without forcing it through a gaping hole.

Specialized has since advanced the Mimic technology with its Mirror saddles, which use 3D-printed polyurethane to fine-tune the densities in each area of the saddle and further reduce pressure on the sit bones. The company no longer markets its saddles according to gender, as men also love the Mimic and Mirror models. Other brands have released both women’s and unisex saddles with similar features. But it remains true that arguably the most important innovation in women’s cycling equipment this century happened because one woman had the courage to finally speak up about her saddle issues.

ALISON TETRICK SERVED as the face of the Mimic campaign. But despite all the interviews she’s since done, she was still “slightly terrified” when we got on the phone. To this day she is perhaps the only American female professional cyclist to go public about her labiaplasty. Why is this so difficult for women to discuss?

For starters, most women are uncomfortable talking about their genitals. Many of us don’t even have the language for it. “Young children, especially girls, are rarely given accurate terms,” says Debbie Herbenick, PhD, director of the Center for Sexual Health Promotion at Indiana University. That lack of vocabulary and overall discomfort with discussing sexual function follows many of us to adulthood. In a survey of more than 1,000 women, Herbenick and her colleagues found that just 42 percent felt comfortable using words like “clitoris” with their partners, while 54 percent felt it was embarrassing to talk about sex with their partner in explicit ways. Herbenick says that having both the language and the comfort to discuss our genital areas is important for women’s sexual health. “If those terms aren’t familiar to you,” she says, “you lose your ability to communicate in clear ways with a nurse, doctor, or new partner.” Or, in the instance of saddle injuries, with a bike fitter, coach, or fellow cyclist.

When I started reporting this story, I too felt awkward discussing the topic with sources—we would talk in coded language. Then I decided to start each interview with a quick review of terms, and discussions became more comfortable and informative. A woman could now tell me that her labia majora became enlarged, instead of grasping for vague euphemisms like, “It wasn’t pretty down there.”

A cultural stigma against labiaplasty may be another obstacle to transparency, as many people believe the surgery is purely cosmetic. Heather Furnas, the plastic surgeon and Stanford professor, got so exasperated hearing that women were getting labiaplasty only to look like porn stars that she wrote a research paper to dispel that myth. Some academics have also associated labiaplasty with aspects of female genital mutilation. But both Furnas and Angelica Kavouni, MD, a London-based plastic surgeon who has performed countless minora reductions for cyclists, say only a small portion of their patients seek labiaplasty just for aesthetic reasons. Furnas compares it to breast-reduction surgery. “There’s often an aesthetic concern,” she says, “but there’s also a strong functional concern that impacts everyday life. If someone wants to look better, that’s life-changing too.”

In fact, perhaps the most common reason women are reluctant to talk about their saddle issues is that they’re embarrassed. “It really knocks your confidence,” says Lauretta Hanson, an Australian professional road cyclist for UCI Women’s WorldTour Team Lidl-Trek, who, in 2022, shared publicly that she’d had two labiaplasties to resolve years-long saddle issues. “Wearing a swimsuit, having intercourse—you just don’t feel comfortable. It’s traumatic. It sort of feels unfair that cycling, something you love so much, could cause this much damage.”

And even when women do seek help, they’re often dismissed, as Tetrick was. Women repeatedly told me they were informed that saddle pain was normal. Elite track and road racer Haley Nielsen, 36, from San Francisco, had a primary care physician who was a cyclist herself; this doctor told her that her persistent cysts and labial swelling were because she wasn’t changing out of her chamois quickly enough. Nielsen, who tells me she always changes out of her shorts immediately (“of course I do”), struggled until she finally found a gynecologist willing to surgically remove a two-inch lump from the left side of her vulva.

This idea that saddle pain is normal may be endemic to cycling, but it may also be rooted in a broader societal acceptance around women’s sexual and reproductive pain. Whether it’s gynecological procedures, period cramps, or childbirth, women are often told that pain is normal. “I mean, isn’t that the original sin?” Herbenick says wryly, reciting Genesis 3:16, in which God curses Eve: “I will surely multiply your pain in childbearing; in pain you shall bring forth children.” We don’t give women enough information about how much pain to expect in these experiences, when it should stop, and how to manage it, Herbenick says. Many women anticipate the first time they have intercourse to hurt, for example. “And unfortunately, they don’t have a sense of when it should no longer hurt.” Some women also suffer unnecessarily from period cramps, because they don’t know that cramps shouldn’t be severe.

In the absence of transparency, women are left to derive their own solutions. Caroline Worrall, the cyclist in Gainesville who tried 30 saddles, found little information about each model online, so if one offered some relief, she’d find another that looked similar and try it next, a lengthy process of trial and error. While searching for a solution, women might push through discomfort for months or years, until surgery or quitting the sport is their only recourse.

Today, Alison Tetrick rejects the sport’s romanticization of suffering, which she believes contributed to the years that people dismissed her saddle concerns. “‘Bike riding’s hard.’ Well, yeah, it’s your lungs and your legs,” she says. “But why are we not addressing comfort? We innovate on aerodynamics and weight and speed, but why are we not thinking about a touch point that can change your life?”

This is why, even though she jokes that she never signed up to be known as “the vagina girl,” she continues to do interviews about saddle issues. “I wanted to take this call because I’m proud of the work we’ve done to talk about hard things,” she says. “And to normalize not the suffering and discomfort, but the process to alleviate that.”

TODAY, IT’S EASY to deride the myopic 19th-century fixation with how cycling could impact a woman’s childbearing abilities. But modern-day headlines can misrepresent saddle issues, too—“Women are getting labiaplasty just to ride their bikes”—and miss the real effect on the health and well-being of women. When I asked amateur cyclists why they went to extraordinary lengths to resolve their saddle issues, their responses made clear that saddle comfort is a deciding factor in their ability to participate in a sport that benefits their bodies and minds so profoundly.

Hannah Knapp, the woman in Salt Lake City who started cycling during the pandemic and developed a massive lump due to her ill-fitted saddle, told me that cycling transformed her world in a way that made the ordeal worth it. She went from being unable to ride more than 10 miles at a time to completing 24-hour, cross-country, and enduro mountain bike races. She met new friends. She went to work for cycling brands. She is now a social media manager at Outside Inc. for the cycling brands Velo and Pinkbike. “My whole life changed,” she says.

Now 55, Caroline Worrall says the sport changed her life, too. When she started riding at 44, it made her a saner, happier person. “It seems like any problem I have can be solved by going out on a ride,” she says. The success she’s had in the sport has made her feel more confident and empowered. Last June, amid hot and muddy conditions that DNF’d more than a quarter of the field, Worrall completed her third 200-mile Unbound gravel race—and stood on her age-group podium for the third time.

Not everyone believes it was worth it. “I wouldn’t be where I am today without [cycling],” says Jacqueline McClure, the former elite racer who had damage to her labia long after she stopped racing. “But I wish I would have asked more questions. Like instead of me telling the gynecologist this is normal, I should have been saying this isn’t normal, what can I do about this.”

Alison Tetrick, seven years after her surgery, now rides and races happily on a Specialized Mirror saddle. Her experience has undoubtedly had an impact on many others. All the amateur women I spoke to had tried the Mimic. “When that saddle came out,” McClure said, “it was a godsend.” Worrall had been excited when she read Tetrick’s story, as it was one of the only public accounts she found. That’s no longer true: Despite having the option to use pseudonyms, every cyclist I interviewed for this piece wanted their names on record, hopeful they could further normalize this conversation.

Some, however, including Worrall, still have occasional saddle problems; and some, like McClure, had issues despite regular bike fits and trying various saddles and shorts. When it comes to women’s cycling equipment, both the research community and the bike industry still have work to do.

But there should no longer be a question of why that work is important.

What to Look for in a Bike Fitter

A professional bike fit is as important as saddle choice. “You can have the best saddle in the world,” says physiologist Phil Burt, “but if it’s not set up in the right place, it can’t do its job.” These are the three most important criteria to consider.

Credentials. A background in biomechanics or physiology, or certification through a program like Trek’s Precision Fit, Specialized’s Retul, or the International Bike Fitting Institute, indicates that a fitter has invested in their knowledge base.

Reputation. Certification alone doesn’t guarantee a great fitter. Andrew Pruitt, EdD, advises asking other riders in your community or members of a local cycling club or team for recommendations.

Approach. A good fitter asks for details about your riding history and the problems you’ve been experiencing, takes a systematic approach to their recommendations, and can tell you why one saddle may be better for you than the other.

Five Golden Rules of Preventing Saddle Injuries

Make good bib choices.

Look for high-quality, dense, and compressive Lycra. It will prevent the chamois from migrating to where it can’t do its job. Pads come in different thicknesses and materials. Endura’s Pro SL bib shorts, for example, use silicone in certain areas of the pad; Endura claims the material won’t “bottom out” like foam.Skip the dryer.

Always air-dry your shorts. Heat damages Lycra and other stretchy materials, and closes the cells on chamois foam, making them less cushiony.Rethink chamois cream.

“If you need it for every ride, something’s wrong,” says expert fitter Andrew Pruitt. You should only need it for the longest or roughest outings. Many creams are water-soluble and can break down with sweat, so for multiday rides, Pruitt suggests mixing petroleum jelly with a triple-antibiotic ointment at a 1:1 ratio to prevent infection on chafed skin.Always pack extra shorts.

For multiday tours, Pruitt recommends bringing a chamois for each day. For grueling, high-mileage dirt or gravel events, he even suggests having a clean pair available to change into at rest stops. “They get so full of sweat and grime,” he says. “Friction is just rampant.”Take a more-is-less approach.

Yes, we’re talking pubic hair. It helps reduce friction by acting like ball bearings between the skin and shorts, so Pruitt advises against hair removal. If you must groom, laser is preferred, as shaving and waxing can leave follicles more prone to infection.

What You Need to Know About Labiaplasty

Labiaplasty can be life-changing, but it is not without risks. Poorly done procedures may result in scarring or even amputation of the labia. Because of the risks, the American College of Obstetrics and Gynecologists discourages the procedure—with some exceptions, including interference with athletic activities. These guidelines can help ensure a positive outcome.

Find the right practitioner. Gynecologists and plastic surgeons can perform surgery on the labia, but plastic surgeon Heather Furnas, MD, recommends looking for doctors who are certified by the American Board of Plastic Surgeons and have been trained in female genital plastic surgery specifically. Ideally, look for a doctor with experience in majoraplasty.Ask for before-and-after photos of the surgeon’s work. Make sure the labia majora look normal and the minor doesn’t look amputated, says Furnas. “Sometimes photos will just show the ‘clamshell’ look after surgery,” she says. “You want to see what the labia minora actually look like, not just the closed labia majora.”Prioritize provider over payment method. While certain labiaplasty methods (e.g., clamping the tissue, cutting it, and then oversewing) are more likely to be covered by insurance, they’re also more likely to result in scarring or excess tissue removal, Furnas says.Recovery takes time. Labiaplasty is an outpatient procedure done under local (more commonly) or general anesthesia. For a week after, Furnas instructs patients to ice the area and to elevate the pelvis to decrease swelling. Tampons and intercourse are no-no’s for four to six weeks, and you’ll probably be off the bike for at least three months. After rides, you will need to prevent swelling with compression or massage or else the issue could recur.

You Might Also Like