Henderson history: Local Democratic Party split in 1924

Henderson County Democrats held two different conventions in 1924, leading to a battle a week later at the state convention over which set of 36 delegates to seat.

There is every indication that the Ku Klux Klan was the wedge that divided the community. Most of the reporting in The Gleaner, however, was about who supported U.S. Sen. A.O. Stanley and who did not; Stanley was one of the KKK’s most vociferous opponents.

I am in no way asserting that everyone who opposed Stanley was a member of the Klan. It seems clear, however, that a large percentage of that faction was either KKK or supported its aims.

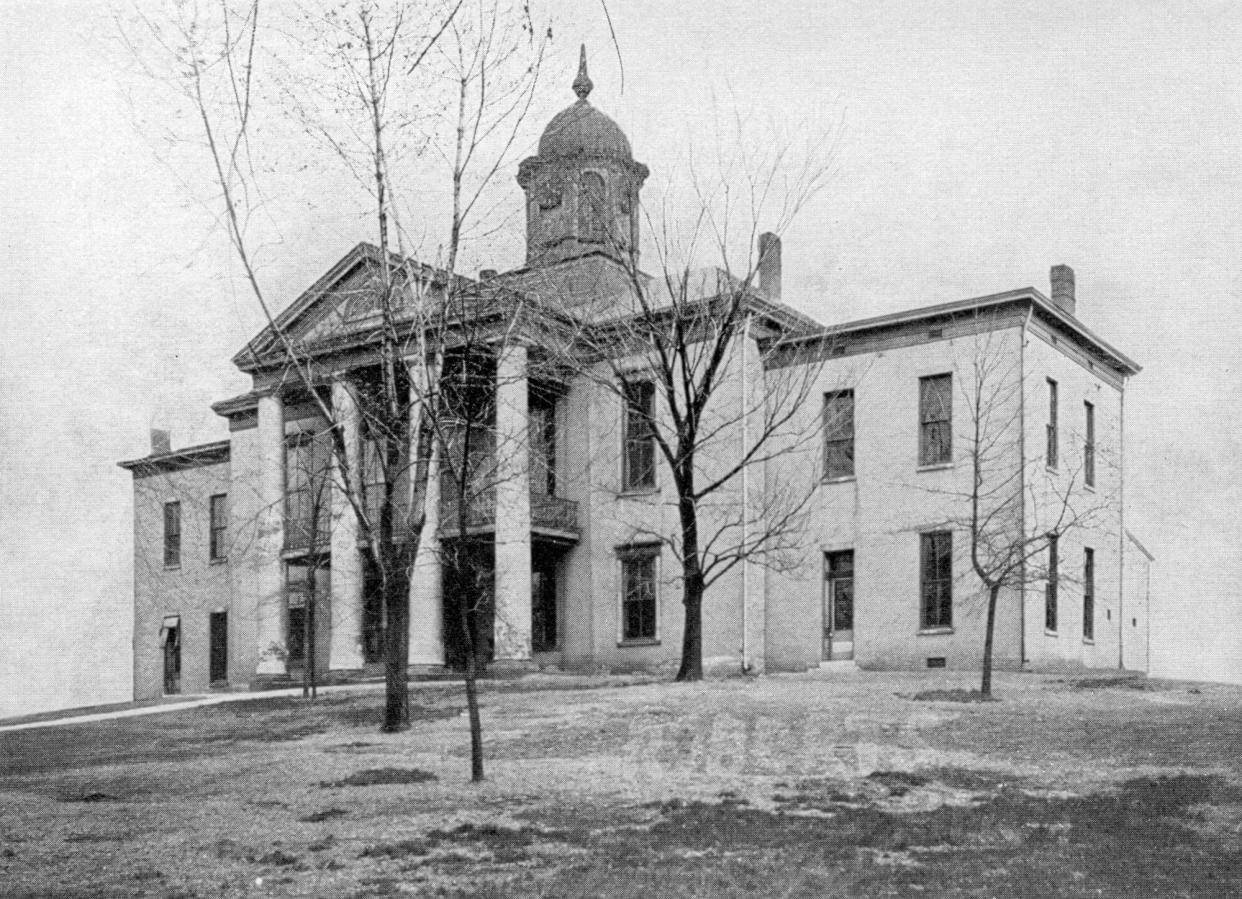

The county convention was scheduled for 2 p.m. May 10 at the courthouse and The Gleaner that day explained why Stanley was at the center of the division. Friends and supporters of Stanley, “without any solicitation on his part,” wanted the state convention to nominate him as a candidate for president that year.

“No candidate will have enough votes to win on the first ballot” at the national convention and should there be a deadlock, Stanley “would probably have as good a chance to get the nomination as any other man.” But getting the support of his home county beforehand was crucial.

The Gleaner of May 11 carried two separate stories about the two separate conventions. One convention, headed by Judge J.W. Henson, was held in the circuit courtroom at the courthouse − where the convention had been advertised − and the other, headed by journalist and local historian Spalding Trafton, was held in the courthouse yard. Although Trafton was an employee of The Gleaner, the reporting did not appear to be skewed in favor of his faction.

The Henson faction appeared early for the convention. “The court room was not only filled − it was packed − seats and aisles, and it is understood that it had been filled for a considerable time previous to the convention…. It was a Henson crowd and it never missed an opportunity to show allegiance to his leadership.”

W.H. “Pete” Soaper, the chairman of the county Democratic Party, didn't even try to wedge his way through the crowd. Instead, he opened the convention in the courthouse yard because the crowd there was estimated at 1,200 to 1,500. The tally of those in the courtroom was 592 people; only seven said they supported Stanley.

Shortly before Soaper called his convention to order, at least two men called up that the convention was being held outside. The Henson faction was in disarray when it realized it had been outflanked.

“A stampede for the stairway was starting when Ben Niles sprang to his feet from a rear seat and urged the people to remain in the court room until Chairman Soaper should come up and properly adjourn to the court yard,” The Gleaner reported. “The rush toward the door stopped.”

The outside convention named 36 delegates and 36 alternates, all of whom were named in The Gleaner.

The inside convention later did the same, but not before Henson gave Stanley a tongue-lashing.

“Stanley was put forward at this time for the purpose of capturing the organization,” he said. In his denouncing “machine politics and crooked politics” he said, “I stand for America first, last and all the time. I stand against the influx of foreign immigration.”

The following day about 1,500 people gathered in Central Park, according to The Gleaner of May 13, and passed a resolution protesting what had taken place at the outside convention.

Henson began by fiercely criticizing the opposition’s tactics. “They ran the steam roller over me yesterday, but they won\'t do it again,” he vowed.

He then put his finger on the crux of the matter. “The opposition, I understand, tried to prejudice our cause by whispering it around that our side was composed Ku Klux (Klan),” he said. “If it was a Ku Klux gang, it was a fine-looking body of men and women. I don’t belong to it, but a lot of smart folks have been saying I did. From what I have read in papers, if they stated their principles correctly, that organization, it seems, stands for the highest ideals of America.”

Those attending that meeting passed a resolution saying that they “protest and condemn the unauthorized, arbitrary and illegal methods used by the chairman of the Democratic County Committee.” The Gideon Bible Class at Immanuel Baptist Temple also passed a resolution unanimously condemning the Democratic chairman, calling his methods “repugnant to all honest, law-abiding, God-fearing Christians.”

The Henson faction hired a special train coach to carry its delegation and supporters to the state convention in Lexington, where the dispute was reported in The Gleaner of May 16.

Marvin Eblen, a member of the Henson faction who was mayor 1926-30, presented to the credentials committee the affidavits of 165 Democrats who swore they had outnumbered the Stanley faction 4 to 1 outside the courthouse, but that Soaper would not recognize their motion for electing Henson chairman of the convention. (Trafton was instead elected.)

Judge J.L. Dorsey of the Stanley faction disputed Eblen’s statements. He maintained the opposition had packed the courthouse with the view of shutting out the opposition, which he said is exactly what they did.The credentials committee – on a split vote – voted to seat the Stanley delegates.

In a separate Gleaner story on May 16 Henson said he had been informed – after the Stanley delegates had been seated – that some members of the credentials committee “said the decision was made in the interest of harmony in Senator Stanley’s race for re-election to the United States Senate next fall.”

A.O. Stanley lost that race in 1925 – which was even more hotly contested. Trafton wrote a letter to the editor, published originally in the Louisville Courier-Journal but republished in The Gleaner of Nov. 8, that tried to put Stanley’s loss in perspective.

The Courier-Journal’s Henderson County coverage of the Nov. 5 election “designated the two tickets as the Stanley and anti-Stanley elements … when in truth Stanley was not an issue. The only issue in this campaign in the city and county races was Ku Klux and anti-Ku Klux.”

The KKK candidates ran under the Democratic banner, Trafton wrote, and their opponents ran as Republicans. (That polarity, by the way, was reversed in Indiana after 1923.) The Democrats and KKK-affiliated candidates in non-partisan races swept the board – although by relatively slim margins in some races.

“The point is that the local press and the correspondent for the Associated Press and other out-of-town papers are controlled and dominated by the local Klan, and they have not stated the matter fairly.

“If the Ku Klux Klan stands for something so wonderful, why do they seek to cover up the fact that this is a Klan victory instead of trying to make it appear as a Stanley defeat?”

Trafton ran unsuccessfully against Eblen for mayor in that election and wrote, “White women – Ku Klux Klan sympathizers – lined up on the outside of some of our polls and jeered at respectable voters who dared to oppose the Klan, calling them ‘bootleggers.’”

He saw fit to add a postscript to his letter: “I am neither a Catholic nor a ‘bootlegger.’ I am a member of the Protestant Episcopal church.”

75 YEARS AGO

Nineteen firms submitted bids to supply equipment for the city’s new power plant, according to The Gleaner of May 17, 1949, which was completed on the riverfront in 1951.

Present at the meeting were the three members of the newly created Henderson Utility Commission: Henry Lee Cooper, Henry Lain, and George Snyder.

The Henderson City Commission had earlier authorized the issuance of $3 million in bonds to build what would be called Station 1.

The Gleaner of May 24 reported the bonds had been sold and $786,689 worth of contracts were awarded.

50 YEARS AGO

The Kentucky Bureau of Highways presented plans for widening Second Street to Adams Lane and building an earth-fill railroad overpass, according to The Gleaner of May 15, 1974.

About 130 people attended the presentation at the courthouse but few were happy with the overpass plans.

“You’re creating a greater traffic problem than the one you’re trying to solve without some north-south movement between McKinley Avenue and Priest Street,” said Maurice Galloway, a representative of the local chamber of commerce.

City Manager John Hefner made the same objection; the city recommended “a direct connection between McKinley and Heilman to keep local truck traffic on these streets.”

Plans were changed, of course, to have concrete pillars supporting the overpass instead of dirt fill.

The current Second Street overpass opened to traffic Dec. 18, 1981.

25 YEARS AGO

An ordinance that would create a historic preservation district for the downtown area was unveiled in the packet for an upcoming Henderson City Commission workshop, according to The Gleaner of May 16, 1999.

The May 21 Gleaner carried the objections of downtown property owners.

“It seems paternalistic,” said Bill Polk. “It sounds good … until you read the fine print,” said Molly Ershig. Her husband, Harvey Ershig, said the ordinance was similar to one that was proposed in 1992 but was quickly dropped in the face of opposition.

That’s also what happened with the 1999 proposal. The Gleaner of July 14 reported the ordinance had been defeated on first reading by a 3-2 vote. That was the last heard of the proposal.

Readers of The Gleaner can reach Frank Boyett at YesNews42@yahoo.com.

This article originally appeared on Evansville Courier & Press: Henderson history: Local Democratic Party split in 1924