20 years and 4 leaders later, U.S. war on terrorism puts focus on presidential powers

WASHINGTON — When President Joe Biden declared an end to the war in Afghanistan from the White House last month, he said he was also closing the curtain on the "mindset" that had turned the mission into a quagmire.

"The decision about Afghanistan is not just about Afghanistan," he said Aug. 31, hours after the last U.S. troops boarded a flight out of Hamid Karzai International Airport in Kabul. "It's about ending an era of major military operations to remake other countries."

More than 7,000 U.S. service members have been killed in action in operations after the terrorist attacks of Sept. 11, 2001, according to the Defense Department. Thirteen were killed in a suicide bombing at the Kabul airport Aug. 26 as they worked to evacuate Americans and U.S. allies from Afghanistan. And estimates of the number of civilians and members of local security forces killed in Iraq and Afghanistan range into the many hundreds of thousands.

What Biden outlined was pointedly not an end to the post-9/11 era. Rather, it was a much narrower admission that an idea once shared by conservatives, liberals and foreign policy elites, including Biden himself — that the U.S. could use force to destroy other societies and then rebuild them in America's image — had proved a failure. And it was an acknowledgment that the nature of warfare, not the enemy, has changed for the world's pre-eminent superpower.

"Moving on from that mindset and those kind of large-scale troop deployments will make us stronger and more effective and safer at home," Biden said. "And for anyone who gets the wrong idea, let me say it clearly. To those who wish America harm, to those that engage in terrorism against us and our allies, know this: The United States will never rest. We will not forgive. We will not forget. We will hunt you down to the ends of the Earth, and ... you will pay the ultimate price."

In the 20 years since terrorist hijackers crashed commercial jets into the twin towers and the Pentagon and heroic passengers downed a fourth plane in a field in western Pennsylvania, America has been engaged in a boundless battle on that score — a fight President George W. Bush termed the "Global War on Terror."

It led the U.S. to deploy hundreds of thousands of troops in Afghanistan, Iraq and other countries; build juggernaut foreign and domestic surveillance operations; re-imagine how war is waged; militarize domestic law enforcement, especially along the southern border with Mexico; flout international humanitarian norms and impinge on civil liberties at home; and spend trillions of taxpayer dollars in service of the idea that such an assault will never happen again.

It appears that there is no going back. Despite the pullout and Biden's attempt to pivot, the most important structural changes to emerge from 9/11 remain firmly in place, beginning with the enlarged role of the White House.

Academics, national security experts and elected officials say the authority of the president has grown geometrically since 2001 in ways that touch nearly every facet of American life.

"What's happened is the expansive view we've taken of war powers, which we view as necessary in the aftermath of 9/11, has crept into the non-war powers," said Claire Finkelstein, a professor of law and philosophy at the University of Pennsylvania who specializes in national security, ethics and democratic governance. "The same trends have been passed from one administration to another, and it almost doesn't matter which one you look at. It's all the same."

Biden is choosing to use the powers his office has taken and been granted, through two decades of executive actions, new laws and the deference of Congress and the courts, in a different manner. But he is not giving them up.

Congress authorized the war in Afghanistan, but it was the presidents — Bush, Barack Obama, Donald Trump and Biden — who determined its course and brought it to an end. Similarly, as Biden suggested by vowing to hunt down terrorists, he continues to fight the broader global battle that Bush initiated.

The immediate and long-term U.S. responses to the 2001 attacks have intractably altered the courses of foreign policy, domestic politics and U.S. culture. In some cases, such as Congress' giving the president virtually unlimited power to wage war under the 2001 authorization of the use of military force, the changes were initiated by the assault and a direct response to it. In others, such as a shift from more lax immigration laws to a hardening of the U.S.-Mexico border, they were a less linear reaction to heightened fear.

"Prior to 9/11, there was gradual movement to relax our conception of the border and to have a more globalized perspective," said Joseph Margulies, a law professor at Cornell University and author of a book about how the attacks transformed American national identity. "The idea of the border as a dangerous place expanded and also grew exponentially. It dramatically accelerated what Trump later articulated as this fortress America."

The start of the wars

Three days after the attacks, the Senate and the House voted to authorize the president to use military force to retaliate against the perpetrators and avert future acts of terrorism. The key 60-word provision granted the president the sole power to determine which "nations, organizations or persons ... planned, authorized, committed or aided the terrorist attacks ... or harbored such organizations or persons."

It is almost impossible to overstate the degree to which Americans were shaken by the attacks — and unified in their fear, desire for revenge and insistence on preventive measures to thwart terrorism. The country had just endured the bloodiest day on U.S. soil since Pearl Harbor, and the ongoing threat appeared more exotic and imminent — stateless terrorists' striking the mainland — than that posed by the overseas Axis powers in World War II.

Only one lawmaker in either chamber voted no: Rep. Barbara Lee, D-Calif. She would get death threats for her opposition to the war in Afghanistan.

"This unspeakable act on the United States has forced me ... to rely on my moral compass, my conscience and my God for direction," Lee said on the House floor. "Sept. 11 changed the world. Our deepest fears now haunt us. Yet I am convinced that military action will not prevent further acts of international terrorism against the United States."

The rest of the discussion that day, in both chambers, resembled a chorus more than a debating society. Only a handful of lawmakers expressed any reservation at all, and the leading voices of both the Republican and the Democratic parties congratulated one another for their wisdom and bipartisanship. The country wanted blood, and, beyond some minor negotiation between the White House and the Democratic leadership, Congress was not going to parse the particulars of the death warrant.

"It does not give the president a blanket approval to take military action against others under the guise of fighting international terrorism," said Sen. John Kerry, D-Mass., who would go on to challenge Bush as the Democratic presidential nominee in 2004 and serve as Obama's secretary of state. "It is not an open-ended authorization to use force in circumstances beyond those we face today."

A longtime friend, Sen. John McCain, R-Ariz., turned out to be more prophetic.

"This mission is harder, will take longer and ends not with the capture or death of Osama bin Laden but with the destruction of the terrorist networks that threaten our way of life and the defeat of nations supporting and collaborating with this evil," McCain said. "These nations, too, are our enemies."

Before the 107th Congress adjourned for the final time, it would enact a second authorization allowing Bush to go to war in Iraq, create new foreign and domestic surveillance tools granted by the USA Patriot Act, establish a Department of Homeland Security and the Transportation Security Administration, direct tens of billions of dollars in recovery money for New York and the Pentagon, encourage the expansion of NATO and give the president greater authority to approve special visas for criminal and terrorist informants.

"In the months after that, we worked in a totally bipartisan way," former Senate Republican Leader Trent Lott of Mississippi said in a Bipartisan Policy Center interview last week. Indeed, the attacks, which prompted scores of lawmakers in both parties to gather on the steps of the Capitol and sing "God Bless America" on the afternoon of Sept. 11, created the atmosphere for the last extended period of bipartisanship in the Capitol.

Nearly all of the legislation handed power to the president.

"In seeking to guard this nation against the threat of catastrophic violence, our administration gave intelligence officers the tools and lawful authority they needed to gain vital information," former Vice President Dick Cheney said in a speech in 2009. "We didn't invent that authority. It is drawn from Article II of the Constitution. And it was given specificity by the Congress after 9/11, in a joint resolution authorizing 'all necessary and appropriate force' to protect the American people."

At the time, a Republican was president. But his successors, both Republican and Democratic, would all come to find the authority useful in deploying military force around the globe — in Afghanistan, Iraq, Syria, Libya, Somalia, Niger, Cuba and at least a dozen other countries. Like its predecessors, the Biden administration continues to classify the list of organizations and people the executive branch considers to be covered by the 2001 authorization of force.

Republicans found in short order that voters did not blame Bush for the attack, despite intelligence warnings he received about bin Laden's intention to strike inside the U.S., and they used his prosecution of the "war on terror" as a political weapon in the 2002 midterms.

"We can go to the country on this issue because they trust the Republican Party to do a better job of protecting and strengthening America's military might and thereby protecting America," Bush adviser Karl Rove said in January 2002.

Defying historical trends for a president's party in his first midterm, the GOP increased its majority in the House by eight seats and took control of the Senate. Two years later, Bush would take a similar tack — assisted by culture-war issues on state ballots — to defeat Kerry in 2004. A few days before voters went to the polls, bin Laden released a 17-minute videotape referring to Sept. 11 and the coming midterms, which most analysts viewed as a boon for Bush. It was the last presidential election in which a Republican won the popular vote.

Shifting public opinion

By 2006, voters had become weary and wary of war, particularly in Iraq, a country that had not attacked the U.S. The Bush administration's expansive use of executive power to prosecute the wars included warrantless wiretapping, the "extraordinary rendition" of terrorism suspects to third countries where brutal interrogations could be carried out and the establishment of a detention and torture camp at the U.S. naval base in Guantánamo Bay, Cuba.

It also emphasized rebuilding the nations ravaged by U.S. forces as an imperative to prevent U.S. enemies from gaining power. The costs were billed to taxpayers.

Grassroots conservatives came to see Bush as a profligate spender, both in the war effort and in his authorship of expansive federal domestic programs, such as Medicare's prescription drug benefit and the Education Department's No Child Left Behind law. The failure to make discernible progress in Iraq, coupled with Bush's failed response to Hurricane Katrina, opened questions about his competence not just for Democrats but for some Republicans, too.

"It was one thread in the decline of confidence that my generation has exhibited in the integrity and competence of the U.S. federal government," said Rep. Jake Auchincloss, D-Mass., who is 33 and commanded a Marine platoon in Helmand province in Afghanistan.

"George W. Bush still does not get enough opprobrium," Auchincloss said, arguing that Bush lied to the public about "two spectacularly failed" wars. "I can remember what the atmosphere was like after 9/11. The world was rallied behind us. ... He squandered it."

While Americans remained in favor of the U.S. operations in Afghanistan in the mid- to late aughts, support for the Iraq War drained. Democrats swept the 2006 midterms, and they used their new power to signal their readiness to withdraw from Iraq by pushing for a timetable to end the war.

As a presidential candidate in 2008, Sen. Barack Obama, D-Ill., vowed to prioritize ending the Iraq War "responsibly" and "finishing the fight against Al Qaeda and the Taliban." His treatment of the two wars — one misbegotten and one poorly executed — reflected public sentiment.

In March 2003, 75 percent of Americans thought the war in Iraq was not a mistake, according to Gallup. By November 2006, the figure was at 40 percent, and it remained in that range until November 2008, when Obama faced McCain in the presidential election.

But support for the war in Afghanistan remained solid toward the end of the Bush presidency — at 70 percent, according to Gallup — and it lost altitude slowly. Only twice in the last 20 years have more Americans said they believed that war was a mistake, and only by razor-thin margins. In July, 47 percent said it was a mistake, and 46 percent said it was not.

Auchincloss said the wars were different from previous U.S. military engagements that required sacrifice — and commanded attention — from the public.

"We've got to ask hard questions as a democracy about whether we should be able to wage a war on the periphery for an entire generation," he said.

All the while, policymakers wrestled with the potential national security and political consequences of withdrawing U.S. troops. Until Biden, none of them felt comfortable ending a war on his own watch.

"There have been a cascade of misjudgments," Jeh Johnson, who was general counsel at the Pentagon and secretary of homeland security in the Obama administration. He said advisers to presidents counseled that stabilizing Iraq and Afghanistan required counterinsurgency efforts and ultimately nation-building. Removing any piece of the military, intelligence, diplomatic and aid efforts could topple the operations, they were advised by the people who were in charge of the efforts.

"Once you're in that situation, it's tough to back away from it," he said at the Bipartisan Policy Center's virtual seminar. "To his credit, President Biden said: 'I've seen this movie. ... It's time for us to get out.'"

The Obama-Trump muddle

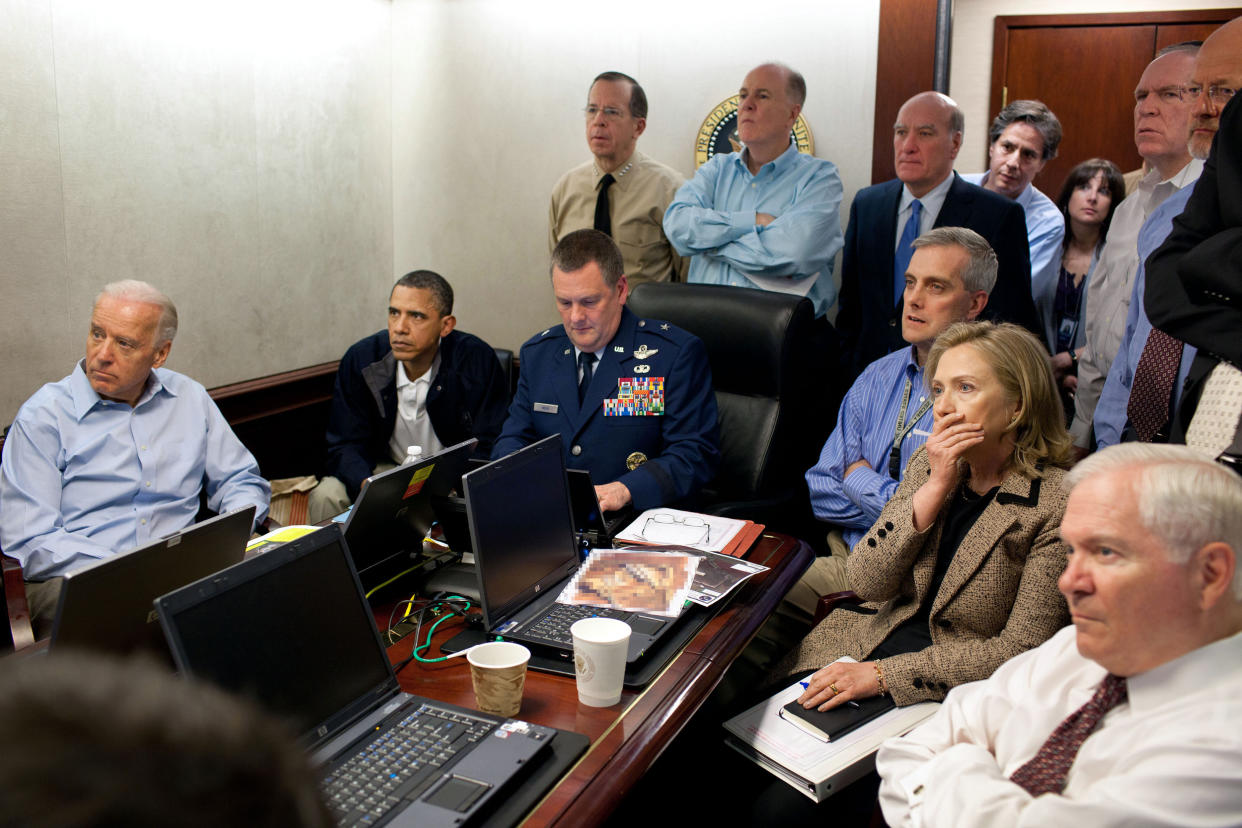

In White House Situation Room meetings, Biden, the vice president, signaled his opposition to the Navy SEAL team raid that killed bin Laden in May 2011, according to people who participated in the discussions. But Biden, who was also against the 2009 surge of U.S. troops into Afghanistan, understood the political value of killing the terrorist behind the Sept. 11 attacks.

During the Obama-Biden re-election campaign the following year, he often repeated the reminder that "bin Laden is dead and General Motors is alive" to shorthand how the administration dealt with what it inherited in the war on terrorism and the aftermath of the 2008 financial crisis.

Killing bin Laden fulfilled Obama's promise to refocus U.S. counterterrorism operations on Al Qaeda and Afghanistan. Yet while the geography and the targets shifted, Obama — appearing, at times, to be engaged in an internal war between ideals and pragmatism — continued a trend toward expansive presidential power, particularly in the realm of national security.

"This is the great tragedy of the Obama presidency," said Spencer Ackerman, author of the new book "Reign of Terror: How the 9/11 Era Destabilized America and Produced Trump."

Ackerman argues that Obama and Trump shared a trait when it came to the war on terrorism: incoherence. Whereas Trump gave many Republican base voters an explanation for the failure of the Bush wars that was both illogical and well received — that elites did not believe strongly enough in the mission to do what it took to win — Obama talked a lot about ending the post-9/11 era while relying on many of the same tools Bush used.

"Obama doesn't end the war on terror. He decides to continue it under greater constraint," Ackerman said, referring in part to an increased use of remote capabilities and special forces operations. "What he decides to do is continue the war under a rubric of far greater bureaucratic internal review over operations like drone strikes and JSOC raids while thinking that is really a substitute for ending the war." (JSOC is the Joint Special Operations Command.)

All the while, the U.S. continued to pour money into its national security apparatus — including a proliferating multiagency intelligence community. As with most breakdowns in national security, politicians attributed the Sept. 11 attacks to a failure of intelligence.

That exonerated political leaders and justified pouring money into new intelligence tools, a trend that has continued unabated as government and industry have raced to revolutionize information-gathering.

"The amount of money that went into 'spot, listen and, if necessary, take out bad guys,' especially for that first 10 years after 9/11, was basically unlimited," said Sen. Mark Warner, D-Va., the chairman of the Intelligence Committee. "We were so afraid of another attack that there was no budget request that wasn't met."

For Warner, the focus on counterterrorism is understandable, but it has come at the cost of allowing "near peers" — such as China and Russia — to leap ahead in developing tools for cyberwarfare. "I think we took our eyes off the ball of near-peer adversaries," he said.

In the U.S., all of the emphasis was on surveillance and strikes.

Margulies, the Cornell professor, said: "I don't think you can underestimate the extent to which 9/11 and the perceived emergency of it drove the technological enterprise — knocked down legal and cultural and political barriers to surveillance. Maybe we would have gotten there anyway. It would have been much slower. It would have been easier to interpose objections."

The tools include drone technology that did not exist in 2001 and enhanced signals intelligence — information gathered electronically, rather than by human sources — which Biden suggests the U.S. will rely on, along with special forces operations, to conduct counterterrorism missions without deploying significant numbers of troops. Obama stepped up the use of those tools while talking about reducing the U.S. military footprint. Biden appears determined to make good on the lighter, less expensive version of counterterrorism that Obama envisioned.

The drawdown of U.S. troops began under Bush, who negotiated a status-of-forces agreement with Iraq's government before he left office. By the time it was fully implemented in 2011, Obama was president. But the radicalization of Al Qaeda in Iraq led to the formation of the Islamic State, the terrorist group better known as ISIS, which drew U.S. forces back into the region.

Obama was so reluctant to get bogged down in a third war on his own that he decided not to go to war against Bashar al-Assad's Syrian government in 2013 before asking for congressional authorization. Congress declined to act on his request.

Like Obama, Trump was of two minds when it came to his war-making power. On one hand, he touted the fact that he did not launch any new wars, as well as his reduction of U.S. forces to 5,000 between Iraq and Afghanistan. On the other, he deployed many of the same tactics — along with a few wrinkles — that Obama favored.

Trump gave commanders in the field broad authority to launch drone strikes outside war zones and stopped the government from reporting on the remote attacks. He also ordered the military to drop a 10.5-ton explosive called "the mother of all bombs" on an ISIS foothold in Afghanistan.

The attack that killed 13 U.S. troops at the Kabul airport last month was carried out by an offshoot called ISIS-K that is operating in Afghanistan and is considered to be far more hard-core than the Taliban.

What has changed — and what has not

Now two decades old, and with a fourth president at the helm, the U.S. war on terrorism has changed dramatically in important ways that are reflected in how Biden and his national security team think about the use of military force.

Twenty years ago, the U.S. fought state and nonstate actors by invading countries. Now, in the era of drone pilots sitting comfortably at domestic bases and small special forces units carrying out discrete missions, American might can be projected with relatively minimal risk to troops, with a small footprint on the ground and, perhaps, with less political peril for politicians.

Foreign-policy makers at the White House and in Congress who often express their confidence in the ability of the U.S. to counter terrorist threats overseas point to the absence of another 9/11-like attack as evidence.

What has not changed, however, is more telling, several national security experts said. The U.S. remains on a war footing. There is not enough appetite in Congress to repeal or rewrite the 2001 war authorization, which has shielded presidents from seeking lawmakers' approval for extended military engagements in a growing number of countries. Sept. 11, 2001, made the nation's chief executive far more powerful — like an elected king, some say — and Congress and the courts have done little to contain that authority.

Judges have seldom intervened, more often than not describing national security policy battles as matters for Congress and the executive branch. Even in blocking the president, the Supreme Court sometimes — as it did with Trump's "Muslim ban" — shows how a desired action can be taken in a manner consistent with the Constitution. Scholars say it is impossible to divorce the growth of the president's national security powers from the exhibition of domestic muscle.

"It's been a one-way ratchet to expand presidential authority," said Finkelstein, the University of Pennsylvania professor.

Warner, a former CEO and governor of Virginia, said it's a "cop-out" for lawmakers to leave all of the war-making power in the president's hands two decades after Sept. 11.

"You need to give the president the authority to act — and act quickly — but there need to be constraints," he said. "By not revisiting the 2001 resolution, it gives Congress the right to complain but not actually have to accept any responsibility. It's a political cop-out."

Warner's fellow Virginia Democrat Tim Kaine is pushing to repeal the resolutions for two Iraq wars — those begun in 1991 and 2002 — before turning to the 2001 Afghanistan resolution. Advocates for the effort acknowledge that it is an uphill battle. Despite the passage of time and the enactment of legislation tailoring the body of post-9/11 laws, elected officials have shown little collective appetite to curb the expanded powers of the presidency.

"The country is fundamentally changed," said former Rep. Adam Putnam, R-Fla., who was in the first of his five terms on the day of the attacks. "The world without TSA and Homeland Security was a simpler time — the world without the Patriot Act. Although the world since that time has not witnessed another attack on U.S. soil — there is more coordination within the intelligence community — it has come at a heavy price, for certain."