What happened to the KC neighborhood where Kauffman Legacy Park is now? Here’s the story

Just east of the Country Club Plaza and north of Brush Creek is an urban oasis of park land, gardens and trails, including an eight-acre nature reserve and lake showcasing native plants and habitat.

Opened in 2000, the Kauffman Memorial Garden and Legacy Park honor the philanthropic spirit of Ewing and Muriel Kauffman. The property, which includes the Kauffman Foundation headquarters and Anita B. Gorman Conservation Discovery Center, offers public greenspace in the heart of the city.

But it is the neighborhood that existed before the Kauffman campus that is the subject of the latest installment of What’s Your KCQ?, a partnership between The Star and the Kansas City Public Library.

Reader Jared Pessetto was studying maps of the area from the 1980s, which showed a sizable residential district around 48th Street and Rockhill Road.

He asked KCQ: “What happened to the neighborhood where Kauffman Memorial Garden is now located?”

The answer involves streetcar transit, flooding, university expansion and, ultimately, urban conservation.

Rise of the Trolley Barn neighborhood

Kansas City’s population was booming by the early 1900s, and its footprint was expanding southward. A robust streetcar system connected downtown to new residential developments such as Hyde Park, Southmoreland and Rockhill. The Troost Avenue and Rockhill Road lines were the major north-south routes to these neighborhoods.

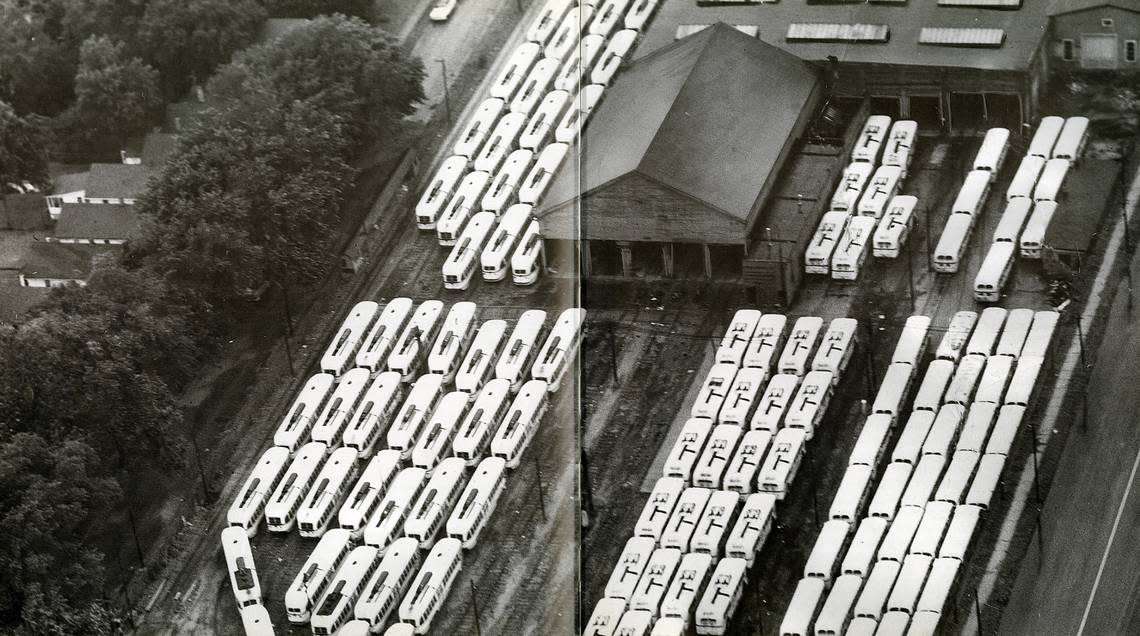

In 1906, a streetcar storage facility opened at 48th and Harrison streets to house trolley cars for the two lines. A trainmen’s building with administrative offices was also located on the property, which encompassed an entire city block.

Streetcar employees moved into nearby homes in the new Fairland and Lahoma additions. Newspaper advertisements from the period touted the neighborhood’s cheap lots, affordable housing and convenient streetcar facilities, and proclaimed that homes were being purchased as quickly as they were being built.

By the mid-1920s, more than 150 properties made up the streetcar barn neighborhood, which extended from roughly Troost Avenue west to Rockhill Road and from 47th Street south to Brush Creek. A cafe, drugstore, laundry and other businesses on 48th Street catered to the growing number of residents.

Trolley Barn’s bohemian shift

The neighborhood’s trajectory changed significantly in 1957 when the main economic driver, the street railway facility, shut down — and motorized buses replaced the city’s streetcar system. The last of the cars completed their final routes on June 23 and parked at the 48th and Harrison streets yard to await sale.

The demographics of the blue-collar neighborhood also began to shift. An eclectic mix of young artists, writers, students and craftsmen moved to the area due to its proximity to colleges and cultural institutions. The new residents created an ethnically diverse and artistic community which was home to two counterculture literary magazines, The Harrison Street Review and The Chouteau Review.

The old streetcar barn became a multi-purpose facility with an automobile auction house and art school among the tenants. In the 1960s, the Women’s Division of the Kansas City Philharmonic Orchestra renovated the building — calling it the Philharmonic Trolley Barn — and held regular fundraising sales there.

The property owner, the Troost Avenue Development Company, eventually ordered the building vacated with the intent of demolishing it and selling the land to the University of Missouri-Kansas City (UMKC).

For years, UMKC had been acquiring properties and holding them in a trust for future campus expansion. University leaders planned to extend the campus to the north, across Brush Creek, with an eye on building a recreational complex.

Preservationists tried to designate the Trolley Barn an historic structure and save it from the wrecking ball, but it was razed in 1978.

But a devastating event the prior year had already spelled the beginning of the end for the Trolley Barn and surrounding neighborhood.

The 1977 flood hits the Trolley Barn neighborhood

A previous What’s Your KCQ? article examined the deadly Brush Creek flood of 1977. A record-setting 16 inches of rain fell on September 12, which resulted in flash flooding of the Country Club Plaza and neighborhoods along Brush Creek, including neighborhoods east of Troost Avenue where predominantly Black Kansas Citians lived. When the waters receded and the damage accessed, there were at least 25 lives lost and over $100 million in property loss.

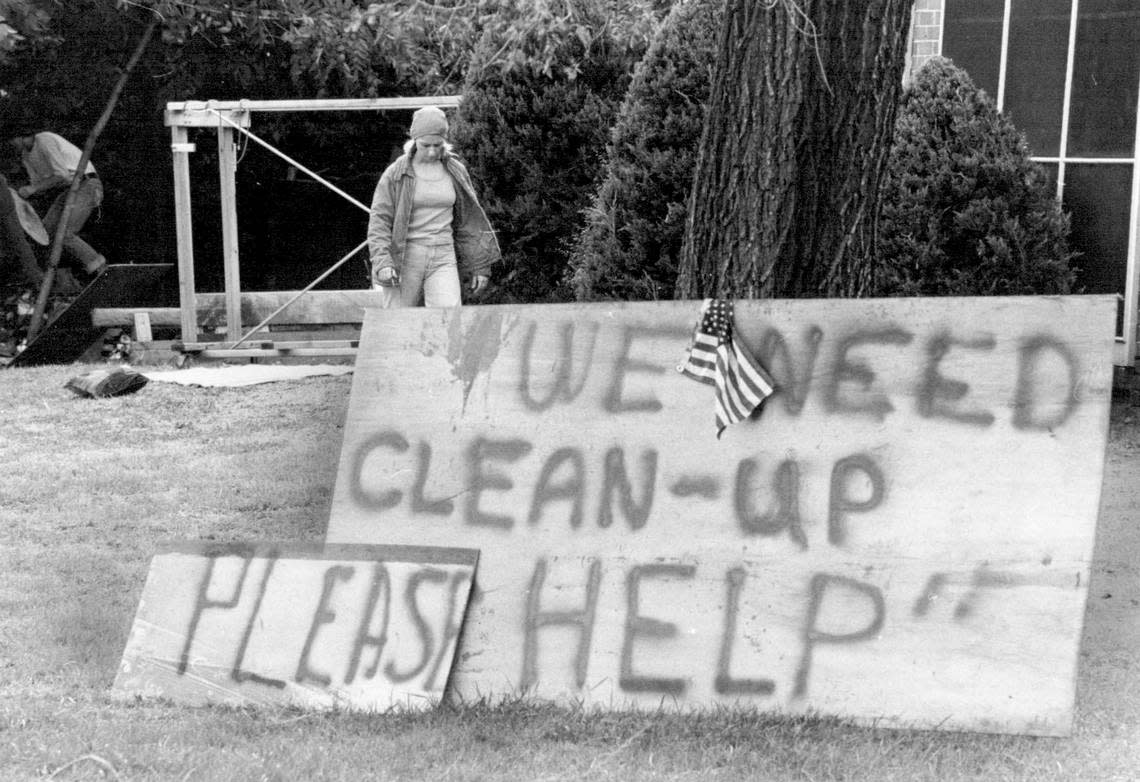

The Trolley Barn neighborhood was hit particularly hard. Some residents moved out, while others chose to pick up the pieces and rebuild their homes and community. Many renters had no choice but to relocate.

At the time of the flood, UMKC owned dozens of rental properties controlled by trustee Miller Nichols, head of the J.C. Nichols Company, through his partnership with the Troost Avenue Development Company. The university saw little incentive to rehab flood-ravaged properties it would eventually level for campus expansion, and gave tenants notice to vacate by the end of the year.

The Brush Creek-Trolley Barn Community Association formed within weeks of the flood to provide property owners with resources to help them rebuild as well as advocate that their input, and that of residents, be considered for the future of Brush Creek and the flood-damaged areas.

In the years to follow, the community association would push back against UMKC’s expansion efforts. Residents charged the university with systematically purchasing properties, allowing them to deteriorate, and then demolishing them, thereby decreasing home values.

Nichols, who oversaw the real estate acquisition program, countered that he was acting in the best interest of the university. “There is no metropolitan university in the United States that has enough land,” he told The Star in 1981. “I’m not hurting the property [value], I’m improving the property.”

In the end, neither party got what it wanted.

With UMKC holding condemnation power, many homeowners saw campus expansion as inevitable and accepted buyouts. As the neighborhood grew blighted, property values plummeted and residents moved out.

Unlike other development projects done in the name of urban renewal that displaced or disrupted predominantly Black communities, the Trolley Barn neighborhood was home to white, middle class families as well as Black families.

“Most of the houses that were south of 47th tended to be folks connected with the university or institutions around there,” explained William Worley, Kansas City historian and author of J.C. Nichols and the Shaping of Kansas City. “It’s kind of an unusual situation in that it’s not a displacement per se of primarily either poor folks or Black folks.”

Resisting displacement

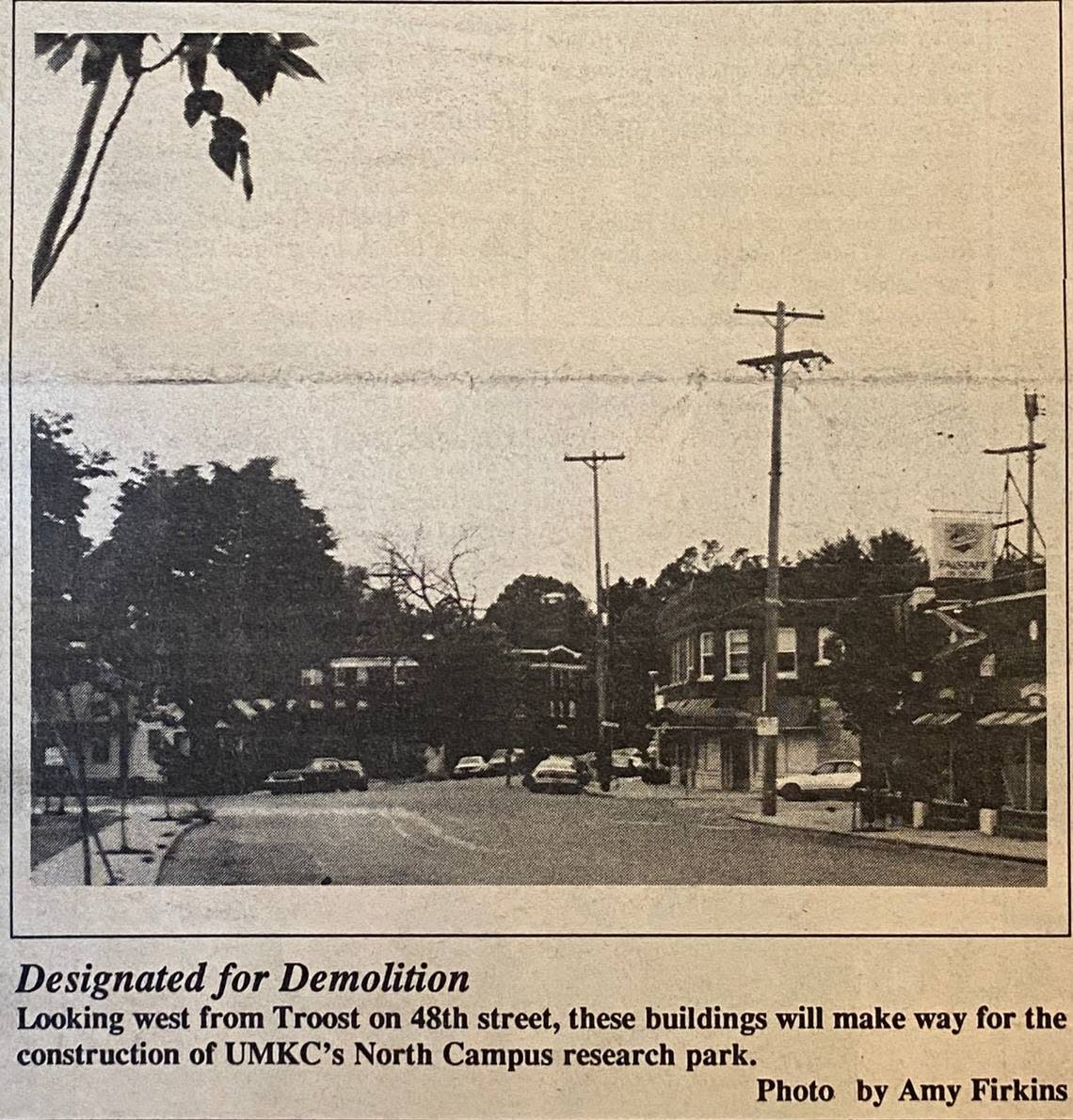

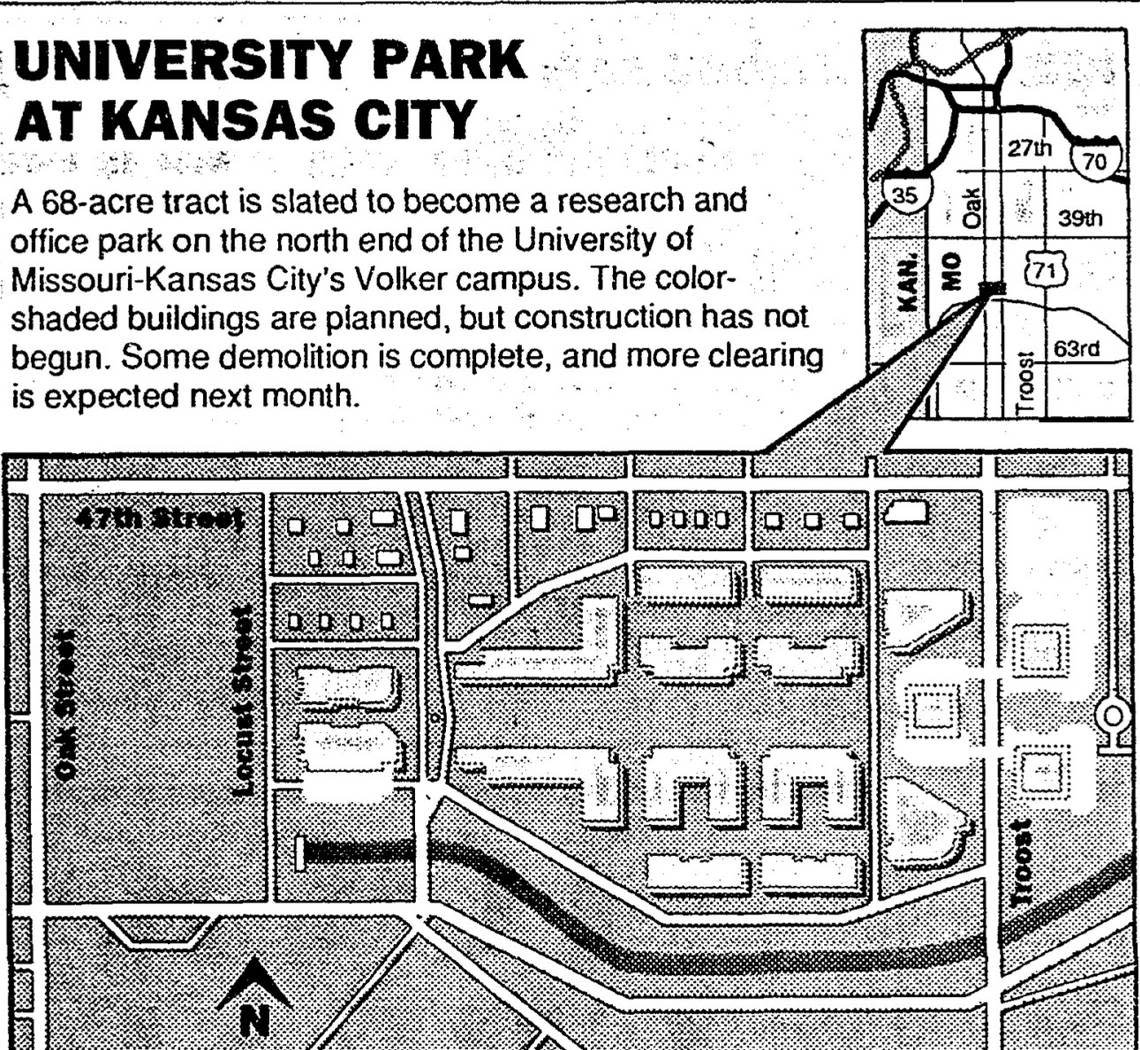

In 1990, the last of the houses was bulldozed to make way for a planned 68-acre research and office park. Later that year, UMKC reached an agreement with health care giant Kaiser Permanente to be the anchor tenant of the new University Park development.

But a more influential neighborhood group to the north, the Rockhill Homes Association, opposed construction of a commercial office building and multi-story parking garage and challenged the constitutionality of a Missouri law allowing for university research parks. Legal wrangling held up the $270 million project, and Kaiser Permanente looked elsewhere to build a medical complex rather than face lawsuits.

In May 1998, UMKC announced that it would demolish 52 homes bounded by Rockhill Road, Troost Avenue, 53rd Street, and 54th Street for a temporary parking lot and future athletic fields. Tenants in university-owned housing were given one year to vacate.

When residents learned that the university was eyeing hundreds more homes as far south as 59th Street for future development, they snapped into action.

Rallies and protests were held and signs resisting the move sprouted up in the front lawns of the residents who would be displaced as well as those in the surrounding areas whose property values would be depressed by the looming threat of university expansion.

In addition to witnessing the destruction of the Trolley Barn neighborhood, many could easily recall the traumatic blow dealt to Kansas City’s Black communities when thousands of homes were lost and residents displaced to clear a path for Bruce R. Watkins Drive.

This time, residents had powerful allies.

Since the threatened neighborhood was racially diverse, the city sought input from the U.S. Justice Department and the Department of Housing and Urban Development for potential civil rights violations. The 49/63 Neighborhood Coalition also got involved. The organization had been established in 1971 with a mission to unite the white and Black neighborhoods west and east of Troost Avenue from Brush Creek south to 63rd Street against the forces of housing discrimintaion and blockbusting.

Finally, Missouri Senator Harry Wiggins stepped in on behalf of residents and facilitated communication between the two sides. Following a series of meetings, UMKC announced they had revoked their plan to level the neighborhood and promised to seek input from community members when planning any future expansions.

Later, when asked about his involvement and the university’s decision to back down, Wiggins quipped, “They know I’m vice chairman of the appropriations committee. I think reason prevailed.”

Becoming an urban oasis

The cleared Trolley Barn neighborhood land sat empty for several years until the Ewing Marion Kauffman Foundation emerged as a possible buyer. The foundation was interested in purchasing most of the acreage allocated for University Park to convert it to an urban nature center and botanical garden. Although initially balking at the offer, UMKC reached a deal with the foundation and sold all but six acres of the property for $12 million – putting an end to the decade-long tug of war over land use.

Groundbreaking for the Kauffman campus began in 1997. The Memorial Garden opened to the public in 2000, and the conservation center the following year.

Now, two decades later, the former Trolley Barn community is a model of urban greening and conservation.

What do you want to know about Kansas City’s history, quirks and curiosities? Let us know at kcq@kcstar.com.