A half century of hope: Lexington celebrates 50 years of honoring Martin Luther King, Jr.

In January 1987, a 9-year-old boy with cerebral palsy walked on crutches in Lexington’s Martin Luther King Day celebration.

He marched with his grandfather, who had himself walked in Washington with King in 1963. With each step, according to reporter Valarie Honeycutt, a placard swung around his neck proclaiming “I have a dream.”

That 9-year-old, Lamin Swann, is now Lexington’s 93rd District Representative to the Kentucky General Assembly. His grandfather, William Parker, headed up minority affairs at UK and helped expand UK’s MLK Day celebrations to a citywide event that on Monday, Jan. 16, will celebrate its 50th anniversary.

“Martin Luther King Jr., and the whole civil rights movement, that is where my thought process begins,” Swann said in a phone conversation on his way to his first legislative session in Frankfort. “Seeing where we were to where we are —we have made progress, but we still have issues we need to face and proceed and correct on, anywhere from housing issues to equality in schools and workplace.”

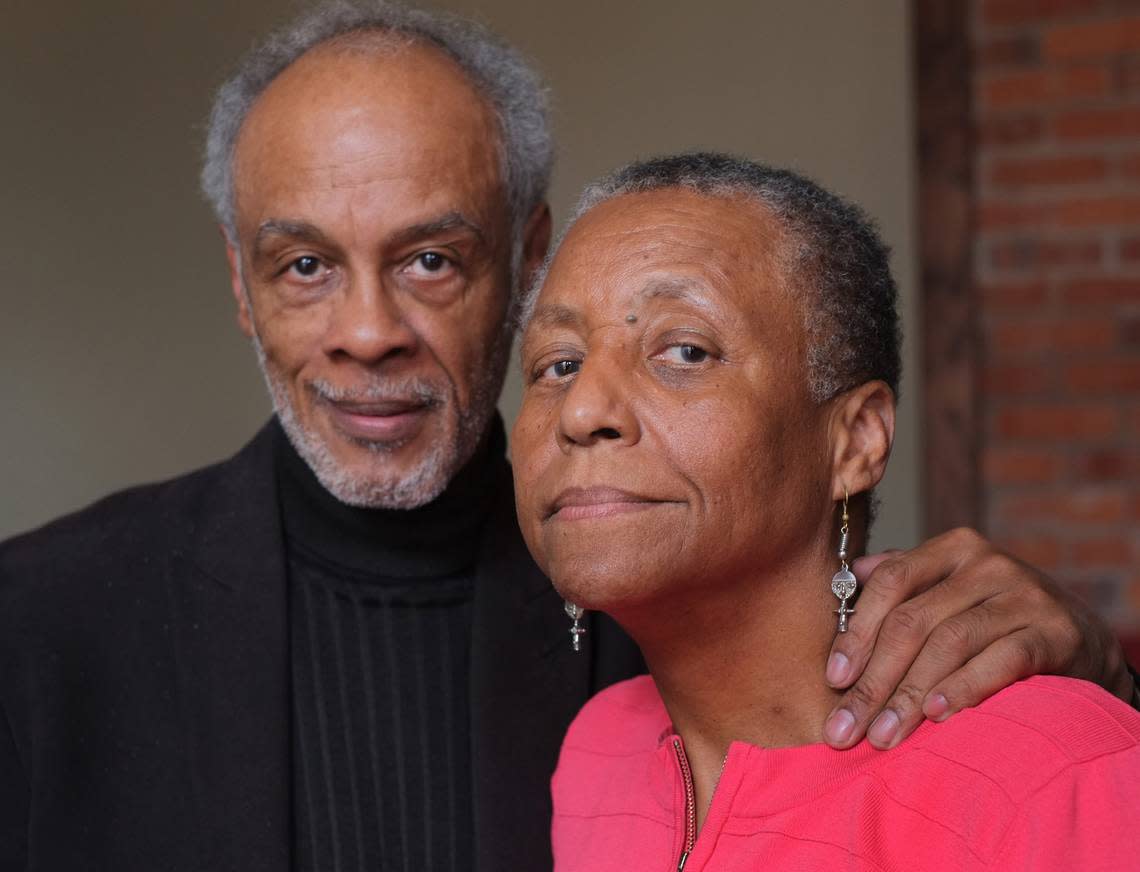

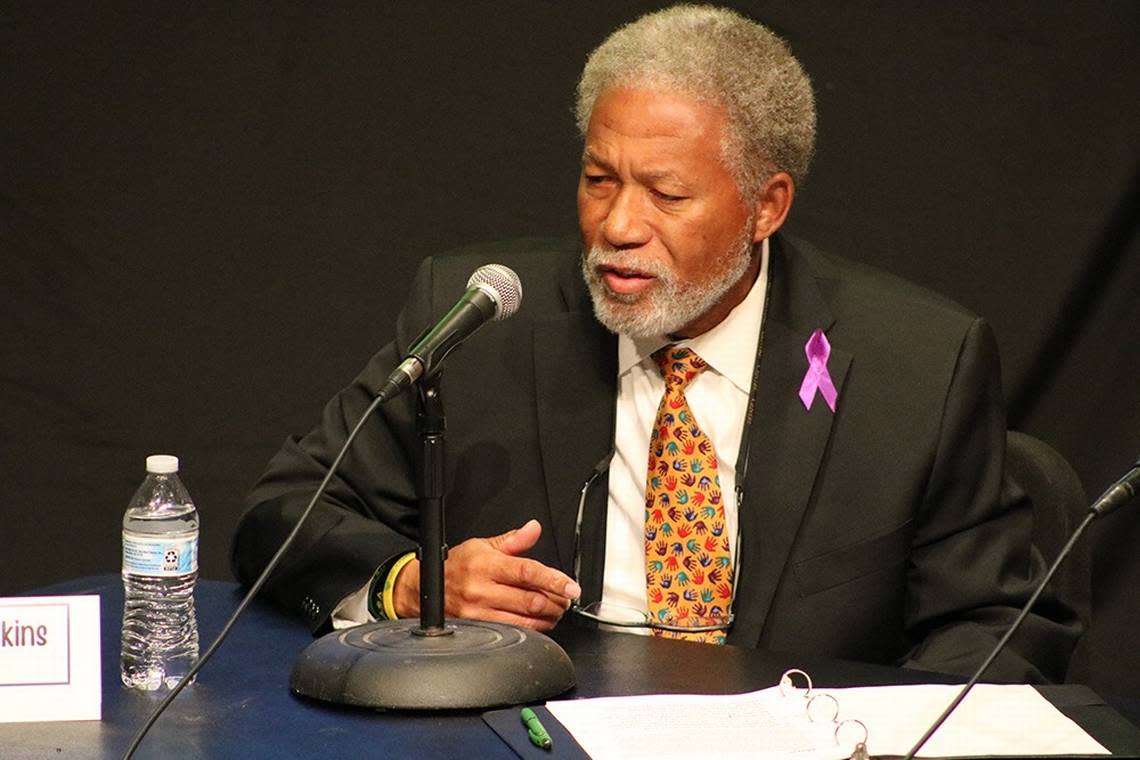

Lexington leaders say that the MLK Day celebration here is among the oldest and most comprehensive in the country. Chester Grundy, who has been involved in 49 of them here, says they have certainly been involved, taking years in advance to plan, or requiring some last minute scrambling, such as that time that a little-known preacher named Raphael Warnock had to cancel at the last minute. (More on that later.)

“I don’t know if I’m really absorbing what it all means,” he said. “It’s such a powerful moment.”

Grundy describes a process that is integral to Lexington’s civil rights history, and in some ways, the most concrete town-gown collaboration between the city and UK. It didn’t start that way.

In 1971, Grundy said, UK President Otis Singletary hired Jerry Stevens to head up the school’s first office of minority affairs. Stevens hired Grundy in 1972. “It was four years after King’s assassination and there was this shift toward open access, with white universities making more of an effort to recruit Black students,” he said.

Against the backdrop of a national push to make MLK Day a national holiday, Stevens and a social work professor named Edgar Mack decided to hold a commemoration on campus in 1973. It included then and for a few more years, a candlelit walk through campus that ended at Memorial Hall, with music from groups like the UK Black Voices or gospel singers and some community speakers.

“If it attracted 75-100 people, it was considered successful,” Grundy said.

In the 1980s, UK hired William Parker (for whom UK’s Parker Scholarships are named). He had a vision of expanding the King program to become a partnership with the city. Then-Mayor Scotty Baesler agreed, and in 1986, the first combined event took place, with a march that circled downtown and a program at Memorial Coliseum, and later the convention center. That allowed more people, bigger sponsors, more high-profile speakers — including civil rights icons like Ossie Davis and Fred Shuttlesworth to movie star Danny Glover — and the idea that Martin Luther King deserved celebrating by the entire community. Despite the often bone-chilling cold that often seems to occur in mid-January, the march and program regularly attract several thousand people.

“It’s been the model we’ve used ever since,” Grundy said. And while some years have been smoother than others; “some years I’ve said I’ve only just survived,” he laughed. Take 2019, when the featured speaker was Rev. Raphael Warnock, the pastor of Ebenezer Baptist Church in Atlanta, Ga., King’s former church.

A week or two before the event, Grundy got a call from Warnock. “He said ‘I can’t be there and I can’t tell you why now, but if I’m not in my church on MLK Day, there would be serious ramifications for me and the church.’”

He helped Grundy find another speaker, Virginia pastor Delmon Coates. Only later did Grundy piece together the story that appointed Republican Georgia Sen. Kelly Loeffler suddenly asked to speak at Ebeneezer on MLK Day. Warnock must have already decided to run against her, and couldn’t let her speak without his presence there. We all know what happened after that, and Warnock went from being a pastor to one of the most consequential senators in the U.S.

The celebrations are important because they allow the different generations to teach and learn about King, from those who marched with him, to those just learning about this life, said UK history professor Gerald Smith, an editor of the King Papers.

“People learn what is means to participate in a march, or have the opportunity to hear some outstanding speakers, many of whom were close confidantes of King,” Smith said. “It’s making sure that history is told from one generation to the next, pushing us beyond the dream.”

Progress and backlash

What does MLK Day mean these days, when we exist in this strange half-world between near-total acceptance of the civil rights movement that he fronted and a determined effort by many to deny even teaching it in schools? We still live in a world of the war, greed and racism that King fought so valiantly against, where so many Black children still live in poverty and Black adults are still preyed on by police.

Yet here in Lexington, we can see manifest progress — a historically diverse urban county government, a Black police chief, Commonwealth’s Attorney and County attorney. Georgetown and Danville just elected the first Black mayors in their history.

Grundy is one of many who in some ways regrets the ubiquity of King as we choose to remember him, stuck in amber at the Lincoln Memorial in 1963 speaking of his dreams, when we could learn more these days by listening to his last speeches against militarism, specifically the Vietnam War, racism and poverty before he was killed in 1968.

“There’s so much to learn from his spiritual and political growth,” Grundy said. “By 1968, he had made this decision that regardless of the price, he had to respond to his conscience, which is ultimately what resulted in his assassination. He continues to be so relevant to what we’re going through right now, he needs to be in our ear.”

King’s lament in a 1967 speech about the triple evils of racism, excessive materialism and militarism echoes what civil rights leaders today lambaste as politicians make a strawman of issues like critical race theory and try to whitewash America’s shameful racial history in our schools.

“Ever since the birth of our nation, White America has had a Schizophrenic personality on the question of race, she has been torn between selves. A self in which she proudly professes the great principle of democracy and a self in which she madly practices the antithesis of democracy. This tragic duality has produced a strange indecisiveness and ambivalence toward the Negro, causing America to take a step backwards simultaneously with every step forward on the question of Racial Justice; to be at once attracted to the Negro and repelled by him, to love and to hate him. There has never been a solid, unified and determined thrust to make justice a reality for Afro-Americans.

“The step backwards has a new name today, it is called the white backlash, but the white backlash is nothing new. It is the surfacing of old prejudices, hostilities and ambivalences that have always been there. It was caused neither by the cry of black power nor by the unfortunate recent wave of riots in our cities. The white backlash of today is rooted in the same problem that has characterized America ever since the black man landed in chains on the shores of this nation.”

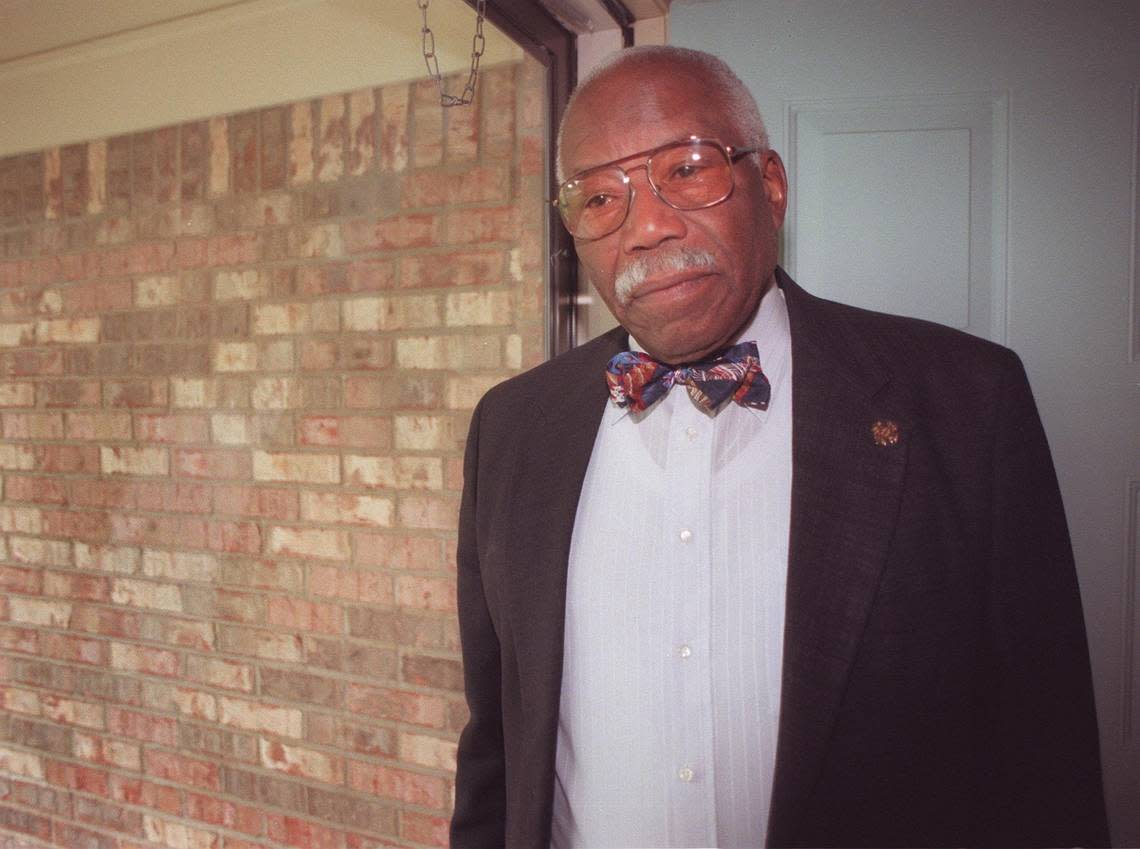

We should celebrate all the stages of King, says J.H. Atkins, Danville’s first Black mayor.

“I was born and raised during segregation, I lived through integration, and now I have witnessed what I call some resegregation or dis-integration,” he said. “Part of my lifetime work is make sure King stays relevant.”

Like Lexington, Danville is making strides with a Black police chief, a Black superintendent of the city schools and the school board Chairman. Danville’s MLK Day celebration includes the Frank X. Walker Literary Festival for students to honor the Danville native and former state poet laureate.

“I have to remind folks that I stand on the shoulders of a lot of people who came before me, trying to develop a set of shoulders so that people who come after me can stand on my shoulders as well — to move this thing we call race relations forward,” Atkins said.

“I have tried to stress to kids that not everyone can be MLK —it takes all of us foot soldiers in these communities to bring about this progress,” Atkins said. “Things are happening in small towns in Kentucky — is it fast enough or enough? I don’t want to be the judge of that — but they are happening.”

In the end, King’s extraordinary life and accomplishments, which are the touchstone of whatever progress we have made in this country, are worthy of 50 years of celebration and many more beyond.

“I think there’s value in people coming together around principles like this — that is us aspiring to be the best we can individually and as a collective,” Grundy said. “I can’t think of many holidays that cut across so many boundaries and are really about elevating the best moral, ethical principles of justice, equality, of opportunity, humanitarianism, empathy, and compassion.”