Grosse Pointe Woods woman: Michigan First Credit Union says concert tickets not fraud

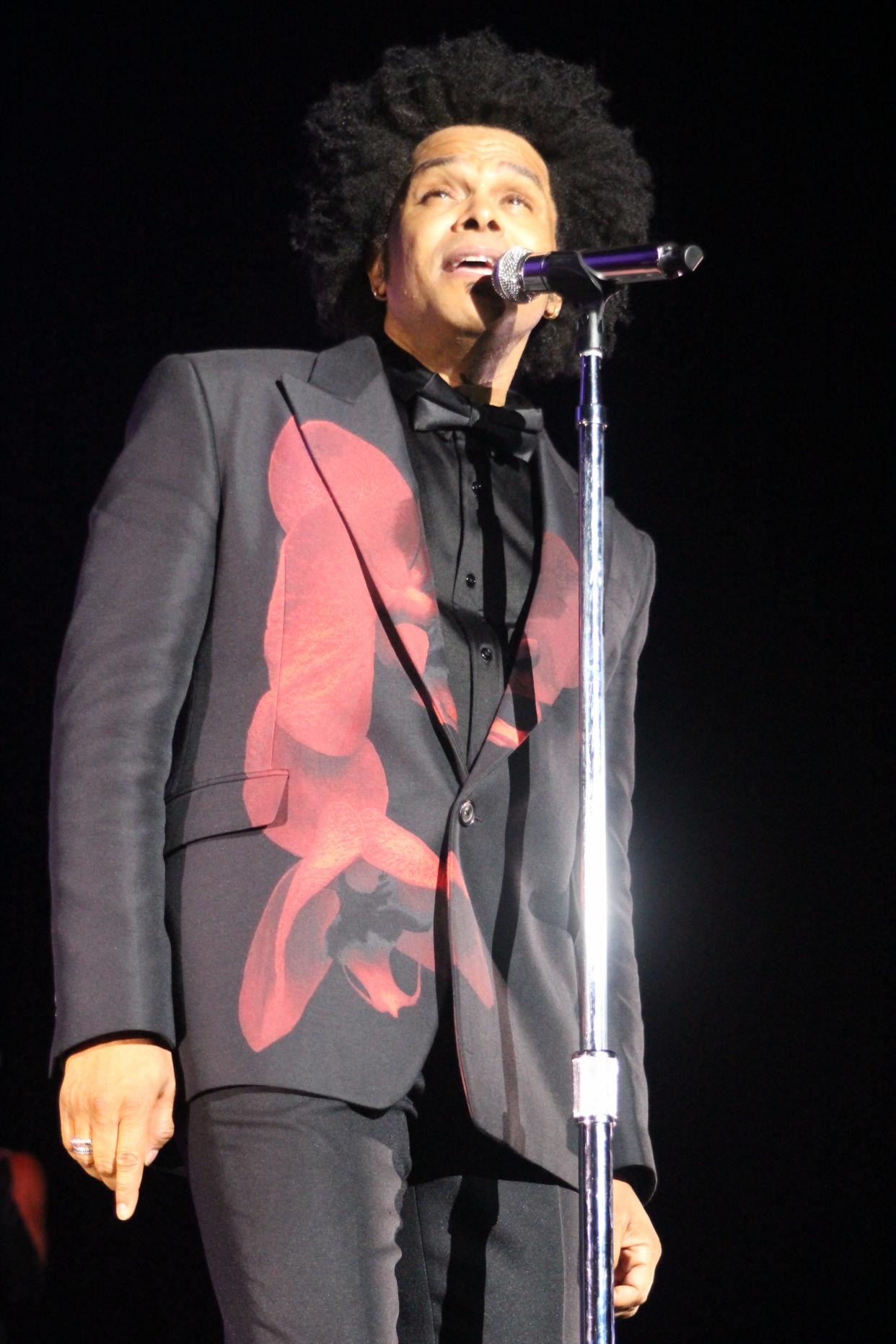

Laura Dewey buys tickets now and then to the Detroit Symphony Orchestra. She's not into rock music, she says, so she couldn't imagine buying concert tickets to Maxwell. She's never heard of Maxwell — who actually isn't a rock star but a Grammy-winning R&B artist who emerged on the burgeoning neo soul scene in the '90s.

She's never been to or had plans to go to Alabama, either, which was one stop last fall on Maxwell's Night: The Trilogy Tour.

Yet Dewey holds a computer printout detailing how her credit card number was used to buy eight tickets for the Maxwell concert on Oct. 7 at the Orion Amphitheater in Huntsville, Alabama. Total cost with fees: $1,379.60.

Her credit union insists that she's on the hook for the purchase.

She feels cheated twice

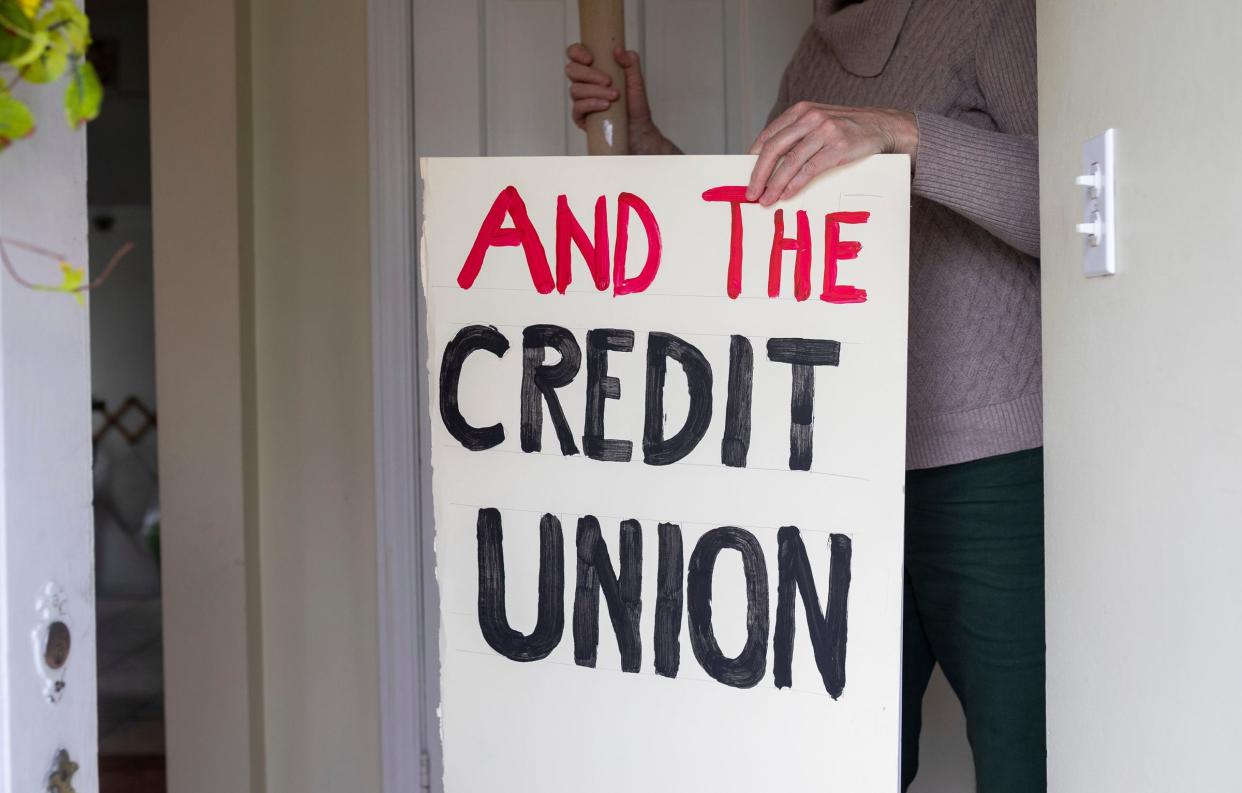

It's a frustrating situation — and one that has driven Dewey at this point to cardboard and big block letters. She pulls a sign from her front closet with giant red, blue, and black lettering. It reads: "Cheated Twice: By a credit card fraudster and the credit union."

After being stalled on many avenues, the divorced mother of two adult daughters is considering marching in front of the Michigan First Credit Union headquarters at Evergreen Road in Lathrup Village. She's not done that yet.

A nearly $1,400 bill is a big hit for anyone. It's more than Dewey's mortgage of $977 a month, which includes with insurance and taxes on her 1,274 square-foot Grosse Pointe Woods home.

"I live check to check," says the freelance copy editor, age 62.

Right about here, the solution seems simple. Alert the credit card issuer and tap into that well-marketed fraud protection. Except, nothing about this story is simple.

The tickets. The cost. How the tickets were shipped. It sure looks like credit card fraud, but the paper trail is being used against her to show that she was emailed the tickets, the purchase went through, so she must have bought eight tickets to a concert in Alabama.

The credit card issuer and the merchant, the online ticket powerhouse AXS, are treating the complaint as if Dewey wants a refund now, after changing her mind. She's saying it was a fraudulent purchase.

"I never used AXS to buy tickets," Dewey said.

A push back on chargebacks is underway

Her story illustrates how fighting an unauthorized charge or disputing a purchase can unravel into a you-said-he-said situation. More frequently, many retailers and e-commerce platforms say they need to protect themselves from consumers who cheat businesses by filing phony disputes with credit card issuers.

"Every consumer is a potential criminal in their eyes," Dewey told me as we sat around her small dining room table in Grosse Pointe Woods in early April, reviewing all the paperwork that she's built up trying to fight off paying $1,379.60 in charges, which now are building up interest.

"We always thought of credit cards as being safer," she said, "but obviously, they're not anymore."

Credit card disputes spiked when consumers got hit by pandemic-related cancellations of events and delays in receiving items due to supply chain issues, according to an October report by the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau.

The financial hit that many merchants face went up, too. And more systems and companies have popped up to help merchants and others fight back unreasonable claims.

What's 'friendly fraud' all about?

A term called "friendly fraud" is used by the credit card industry to describe consumer disputes about goods or services that were authorized and correctly billed. In some cases, a consumer might not know that a family member used their card to buy something. Or maybe, the cardholder bought something fully intending to dispute the charge afterward.

Big areas for fake claims from consumers tend to include purchases involving electronics, luxury goods, cosmetics, auto parts and tires, fashion, and, increasingly, groceries, and business supplies, according to data from Signifyd, a firm that helps companies fight false chargeback claims by consumers. Signifyd works with companies such as Abercrombie & Fitch, Albertsons, Hot Topic, Samsung and Walmart.

Disputes declined in 2021, according to the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau, but rose again in 2022 as spending increased.

In 2022, the CFPB stated, cardholders at major issuers disputed almost $10 billion in purchases and received $6 billion in chargebacks. Chargebacks were up 80% from $3.2 billion before the pandemic in 2019.

How do consumers fight real fraud?

Bad actors, not cardholders, continue to be part of the problem, too. Fraud remains a real threat for many consumers, even as some cardholders try to game the system.

Overall, fraud added up to a more than $10 billion problem for consumers last year, according to the latest data released by the FTC. And local police departments are hearing all sorts of complaints.

Grosse Pointe Woods Public Safety Director John Kosanke told me in a phone interview that he's seeing complaints from residents about fraud all of the time — phone calls claiming to be from DTE Energy threatening immediate shutoffs if you don't cough up $1,000 in gift cards now, cryptocurrency scams, text messages that claim to be from your bank when they aren't.

Many times, he said, residents say they were encouraged by their bank to make a police report.

"You can't have that false sense of security that this won't happen to me," said Kosanke, who regularly talks to local groups about scams.

It's best to take action immediately to report credit card fraud and contact an issuer by phone on the number on the back of your card. Tell the customer representative you think you're the victim of fraud. Ask to close or suspend accounts. Put a freeze or put a fraud alert on your credit report.

Under the law, your liability for unauthorized use of your credit card is limited to $50. "If someone steals your card, for example, your credit card lender can charge you a maximum of $50 no matter how much the thief has charged on your card," according to an alert by the National Consumer Law Center.

The center notes that if the thief uses the card for a telephone or internet purchase, the lender cannot even charge you the $50. Lenders often will waive the $50 under the Visa and MasterCard “zero liability" policies.

Lathrup Village-based Michigan First Credit Union declined to comment on why Dewey is being stuck with the charges. The credit union sent a final determination letter dated Dec. 14, which Dewey shared with me, indicating that her claim was denied because the "merchant has supplied compelling evidence showing that the transaction is valid." The letter from Chargeback Operations referred to an AXS policy that states that ticket sales are final and refunds are allowed in only limited circumstances, such as if an event is canceled.

The credit union told me through its public relations firm: "We are prohibited by federal law from confirming if someone is a member or sharing specific details about accounts, transactions, or claims.

"Michigan First often works with merchants to resolve disputes, and will review all documentation from the merchant before making a final decision," according to the credit union's statement.

Michigan First sends a final determination letter following a full investigation with facts provided by the merchant, according to the credit union.

Could a scammer have bought the tickets?

After reviewing her story and her paperwork, though, it seems to me as if a few things are being used against Dewey, such as the fact that the tickets ended up being emailed to her. Yet does it automatically mean that a scammer wasn't involved?

Not necessarily.

Scammers could have used Dewey's account number to go online to buy Maxwell tickets at the AXS site, perhaps to use or resell later, but they could have bungled the job, according to fraud experts.

Hackers might have engaged in an account takeover where "the threat actor forgot to change the receiving email before ordering the tickets," according to analysts from the digital investigations firm Nisos.

Amy Nofziger, director of victim support for the AARP Fraud Watch Network, said online crime is increasingly evolving. She's not heard of a surge in complaints where scammers buy tickets online to concerts or sporting events to resell. But oddly enough, it did happen to her sister.

In her sister's case, scammers attempted to buy tickets online fraudulently at Ticketmaster. Her credit card issuer reached out and asked her if she was making the purchase, and she said no. Nofziger said the charge never hit her sister's credit card. Her sister never saw tickets in her email.

Nofziger said it is possible that criminals could have gotten ahold of Dewey's credit card number, opened up an AXS account, and planned to intercept the tickets going to her email. Dewey still had her plastic credit card but speculates that her card number was stolen, maybe via a skimmer installed at a gas station or elsewhere.

"But in this case, something was interrupted," Nofziger said. "They couldn't access the tickets. Maybe they decided it wasn't worth it."

"But we have eight unused tickets," Nofziger said, "and the victim is being held responsible for those."

According to the paperwork included in the Dec. 14 final determination letter, the tickets were bought Oct. 5 shortly before 10 p.m. Central time or about two days before the actual concert in Alabama.

The cardholder's bank approved the transaction, according to the paperwork, and the tickets were sent but not scanned in. One box on a form even suggested that it's possible the buyer "couldn't attend the event."

That's likely true, I must add here, since Dewey lives in Grosse Pointe Woods and the concert took place in Huntsville, Alabama. We're talking about more than a 10-hour car ride. (I once made a car trip from the Detroit area to Huntsville, so I can add as an aside that it's not exactly a quick jaunt.)

It does make your head spin.

Is it a refund dispute or fraud?

Dewey first reached out to me by email on March 20 and we've had several conversations. But she's had no luck getting the charge removed from her account, even though she continues her fight.

The merchant, the online ticket platform AXS, appears to be claiming this is a case where the cardholder received the goods and thus it's about a disputed refund, according to Chi Chi Wu, staff attorney at the National Consumer Law Center in Boston, who reviewed some of the correspondence that Dewey shared with me.

But, Wu noted, Dewey is claiming actual fraud or unauthorized use, which is a different type of issue.

"This is a regulated financial institution that is supposed to be following federal laws that specifically protect consumers from what is happening to this woman," Wu told me by phone.

From what Wu could read based on the paperwork, she says, Dewey seems to have "the bad luck of a merchant that is pushing back hard and an issuer who is not backing her."

Wu suggested that Dewey might try to send a second dispute to the credit union with the police report that she filed and maybe explain that the tickets went to her email address, but she never ordered them.

"They still might not accept it," Wu said. But Wu said Dewey should send the credit union the police report that she filed at the Grosse Pointe Woods police station on Jan. 9 to "build a record that her dispute was about actual fraud/unauthorized use, not a disputed refund."

Wu said Dewey's situation is an unusual case, one where Dewey ultimately may need to contact an attorney to enforce her rights under credit card law, perhaps by reaching out to find an attorney through the National Association of Consumer Advocates.

"There are cases where the credit card issuer sides with the merchant. It happens," Wu said.

Merchants see an uptick in false claims

Merchants say credit cardholders are increasingly making false claims after a purchase to obtain goods or services for free, according to the 2024 Global eCommerce Payments and Fraud Survey done by the Merchant Risk Council, an industry group that explores online fraud problems.

The uptick in false claims is blamed on inflation, according to the report, as well as some consumers "learning how to game the system" by turning to online tools and how-to-tips to engage in refund abuse or misuse by the cardholder.

Retailers don't want to get stuck paying the bill. The report noted that more than 77% of merchants successfully blocked or reversed first-party misuse disputes by using updated "compelling evidence rules" when a physical credit card isn't present in the transaction. Visa updated such rules in April 2023 to combat "friendly fraud." Such evidence involves proof the cardholder participated in the transaction, received the goods or services, or benefitted from the transaction.

AXS is claiming that her card number was stored on her account with the merchant, according to the paperwork that Dewey shared, and AXS said they confirmed the card with the CVV code on the back.

Crooks, of course, can gain access to a CVV code, as well as a credit card number.

Dewey says that the fraudsters opened the AXS account, not her. She's had trouble closing that account as well, because a phone number that's different than hers appears to be associated now with that account.

One issue appears to be the no-refund policies of the online ticket seller, AXS. Typically, if someone changes their mind about buying tickets online, they're stuck reselling those tickets. They don't get refunds if they just don't want to go to the concert.

I attempted to reach out to AXS at several times in the past few weeks, including conversations on a chat line, calling a general line and making a phone call with one executive found online. Crickets.

The only response I received was when I reached out via LinkedIn to contact Janet Usher, vice president and legal counsel for AXS. Her replied back: "Please have the customer contact our customer service team at: customerservice@axs.com or 1-888-929-7849."

I passed along the note to Dewey, who said she waited 30 minutes one day on the line and couldn't get through. She emailed a letter to AXS.

In the follow-up letter to AXS, Dewey said that she only learned about the emailed tickets after talking about the charge with her credit union and the credit union told her that that the tickets had been emailed to her. After that, she searched her emails and found one saying "Your Tickets Are Here" dated Oct. 7, 2023, at 10:38 a.m. The email indicated that the tickets could be downloaded.

Dewey says the tickets were buried in dozens of emails. Dewey, who is politically active, pointed out that she was focused on the news of the day, not her email, on Oct. 7 when the Hamas-led attack on Israel broke out and triggered an ongoing war.

Dewey runs into a lot of dead ends

After an investigation, Dewey's fraud case was closed Dec. 26. The credit union declined her claim and put the charges for the tickets on her credit card bill in late December. Interest started building.

Ever since then, Dewey has taken several more steps. She filed a police report in early January, which stated that she was contacted by the credit union on Oct. 5 asking if she bought concert tickets online. She said she told them no and was told the charges would be denied.

Dewey told me in April, though, that she rechecked her credit card statements and it appears the charge did go through on Oct. 6.

"For some reason, I thought the credit union didn't allow it when I told them the charge wasn't mine," she said. "Then, they reversed that charge on Oct. 24 and charged the card again in December" after the investigation was concluded.

She wrote a letter to the president of the credit union, dated Feb. 23, where she noted that she has been a loyal credit union member for more than 42 years, joining when she was a student at Wayne State University. She has her mortgage there. She does not expect, she said, "to be treated by the credit union in this shoddy manner."

Dewey has hit one dead end after another. No relief after complaining about her credit union by contacting the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau, the Michigan Department of Insurance and Financial Services, the National Credit Union Administration, and the Better Business Bureau.

The Michigan Department of Insurance and Financial Services reviewed documentation provided after the credit union’s dispute process, according to a letter that Dewey shared with me.

The credit union's response, according to the letter, indicated that the credit union reviewed her concerns regarding the disputed AXS transaction and explained that identifying information related to the purchase corresponded with Dewey's contact information, including the emailed tickets.

The state regulator also noted that the credit union, as a courtesy, contacted the merchant on Jan. 5 to gain additional information. "However, they were unsuccessful in their attempt."

Dewey, not surprisingly, is upset with being stuck with the bill.

She would like some breakthrough where she doesn't owe the money. But she also would like other consumers who might face the same problems relating to fraudulent ticket purchases or denied claims involving a credit card to know they're not alone — and they could need to keep fighting back, just like Dewey plans to keep doing.

CORRECTION: An earlier version of this story misstated the name of the financial institution in this dispute. The institution is Michigan First Credit Union.

Contact personal finance columnist Susan Tompor: stompor@freepress.com. Follow her on X (Twitter) @tompor.

This article originally appeared on Detroit Free Press: Michigan First Credit Union won't call her concert ticket bill fraud