A Green Bay woman was one of the first female combat soldiers. She died without veteran status.

Months after Green Bay native Martina Heynen deployed to Paris to serve in World War I, the Green Bay Press-Gazette cheerfully described her service as a "vacation." Her send-off overseas was described as "a pretty dinner party" with tables "prettily decorated in cut flowers and attractive name cards."

But nothing about World War I, or where she and the other all-female volunteers from across the United States were headed, could be described as a vacation. "Pretty" did not enter into the vocabulary at the wooden barracks where the women were stationed at the frontlines, and where they lived under constant threat of shells, shrapnel, mustard gas and disease. And certainly, the trip overseas, riddled with German U-boats, risked certain peril for Heynen and her crew.

Heynen was one of the 223 female volunteers who served as switchboard operators for the Army’s Signal Corps during World War I. They became known as the "Hello Girls," a diminutive name given their salvo of responsibilities, the societal norms they bucked and the sacrifices required of them.

They volunteered as soldiers in the first World War before they were given the right to vote, which would take another another two years to attain. And it would take another 58 years after that before any of these women were recognized as veterans.

Not a lot of people know about the Hello Girls, a fact that is beguiling to James Theres, a veteran and filmmaker behind the 2018 documentary "The Hello Girls."

"The truth is, don't we always remember the first ones to do something? In whatever your field is, you probably have a good idea of who the first was," Theres said. "We know who the first person to step foot on the moon was. We know who broke the barrier in baseball. We know these people. Well, somewhere along the way, we forgot about the first American female soldiers in military uniform."

Carolyn Timbie, the granddaughter of Grace Banker, chief operator of the U.S. Signal Corps' female telephone operators, is featured in Theres' documentary. She's been pushing for more federal recognition of her grandmother, a woman whom she never had a chance to meet. She did, however, inherit her trench helmet, fuses, artillery items, gas mask, her uniform and — in what played a key role in Theres' documentary — a journal she kept from her duties overseas.

Timbie and other Hello Girls descendants believe their grandmothers and great-aunts deserve more than just being granted posthumous veterans status. Their big dream, and one they're attempting for the third time, is to have Congress award a single Congressional Gold Medal to the female telephone operators of the Army Signal Corps known as the “Hello Girls.”

But getting sponsors has been an uphill battle, a fact that flummoxes Timbie, who calls such an award a "no-brainer."

"It would be recognizing them for their historical contributions and for the powerful and brave women that they were," Timbie, who lives in New Hampshire, said. "And to me, it's being able to know their stories. We don't know Grace Banker's story. They're not just 223 women. They're 223 women with their own family histories and stories."

Who were the Hello Girls?

Gen. John Pershing, who commanded the American Expeditionary Force (AEF) in Europe during World War I, made the decision to ask U.S. women who spoke both English and French to volunteer as switchboard operators on the frontlines after it became clear that the men — called "Doughboys" — struggled with the task of communications. Much of that had to do with the fact that switchboard operating had been deemed a women's job. Women comprised more than 90% of the employees at Bell Telephone and AT&T.

While the doughboys scrambled to connect calls as switchboard operators, female soldiers had a masterful, quick hand. Generally speaking, it took the men a full minute to connect calls; the Hello Girls needed only 10 seconds. A lot can happen in 50 seconds at the frontlines of the Meuse-Argonne, the largest operation of the AEF during World War I.

Heynen and her all-female Signal Corps crew took the federal oath for service, which extended the remaining length of the war — which could have meant two days or 10 years, Theres is quick to point out. They wore uniforms, took part in training that included daily military drills, were given ranks, lived among the wooden barracks vulnerable to bombings and worked within artillery range in the frontlines of war.

And it was during the Meuse-Argonne that two of the Hello Girls — Inez Crittenden and Cora Bartlett — perished from the Spanish flu and typhoid respectively, diseases that took more American solders' lives than any military weapon. Many more were injured, as they fled fires lit by German prisoners of war and bomb strikes to their barracks.

But once the war concluded, the Army chose not to recognize the Hello Girls as soldiers. The Army concluded the women had operated as citizens, not soldiers.

It would be 60 years before that changed. Only three of the original 233 Hello Girls would be alive to receive honorable discharges in 1977. To add insult to injury, most of the women who served as Hello Girls never got recognition for their war efforts changed on their gravestones, a point many descendants of the Hello Girls are working to rectify.

"When the initial call went out, 7,600 women applied. I mean, that's just amazing," Theres said. "The truth of the matter is that during World War I, most of the men volunteered, but all of the women did."

Who was Martina Heynen?

The life of Martina Heynen's father, Michael, serves as its own fascinating tale. Michael Heynen was a well-known Belgian musician who emigrated to Green Bay in 1897, where he continued his auspicious rise as a composer, according to Mary Jane Herber, local historian and special collections manager at the Brown County Library.

The Belgian native, who looked strikingly like Salvador Dalí in his latter years, was the director of the Green Bay City Band from 1902 to 1937. The Dalí doppelgänger was notorious among the Belgians living in Wisconsin and Minnesota, as he served on the Belgian Council, and was even knighted by King Albert of Belgium in 1929.

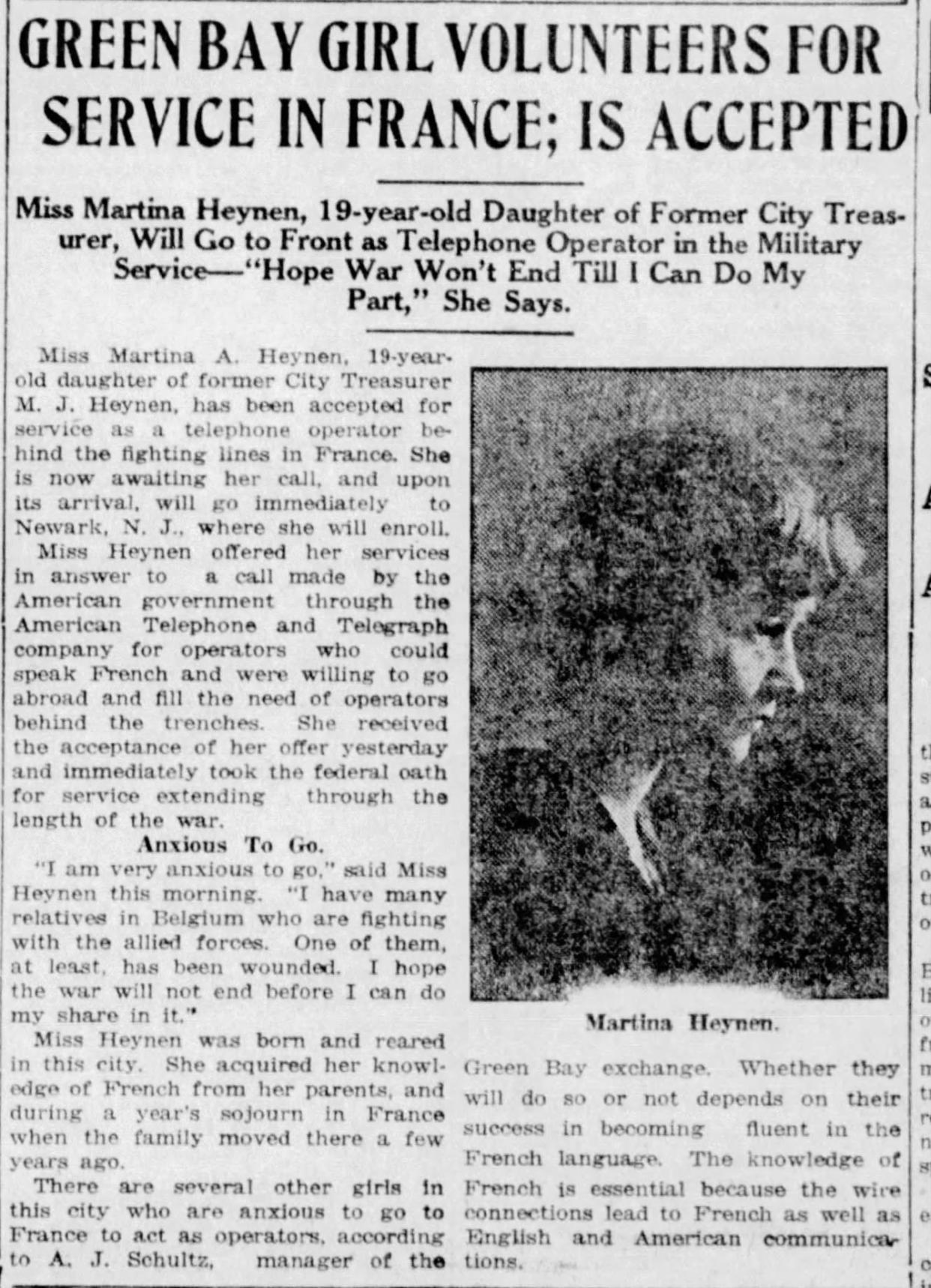

But a little more than a decade before Michael would be knighted by a king, his teenage daughter Martina was about to do something no woman had had the chance to do before. She'd read an advertisement about joining the U.S. Army as a bilingual switchboard operator, a perfect job for Martina, who had been employed at a Green Bay area telephone exchange in 1917 and had "a thorough knowledge of French, gained through the use of it in conversation at home," according to a Jan. 10, 1934, article of the Press-Gazette.

She told the Press-Gazette on Feb. 4, 1918, she was "very anxious to go": "I have many relatives in Belgium who are fighting with the allied forces. One of them, at least, has been wounded. I hope the war will not end before I can do my share in it."

Heynen was one of four Wisconsin women selected to serve in the Signal Corps. The other Wisconsin women were Alice Borresen from La Crosse, Blanche Grandmaitre from Chippewa Falls and Hildegarde Van Brunt, who lived in both Oshkosh and Milwaukee.

Once Heynen arrived in France, she was stationed near Bordeaux for several months, where she transmitted communications between the frontlines and official headquarters at the rear of the offensive. During this period, Heynen served in Crittenden's unit, one of the two women who died in the war.

Then, she was transferred to Paris, where she intercepted and translated hundreds of important military messages to and from the frontlines.

Heynen ended up being one of 28 women selected by President Woodrow Wilson to serve as a phone operator during the Paris Peace Conference, which convened January 1919 in Versailles, just outside of Paris. More extraordinary, Heynen got an even bigger gig, according to a clip from a 1934 Press-Gazette article:

"When the President was (in France) again in 1919 it was Miss Martina Heynen who acted as his private operator during his stay at the Hotel Grillon."

Herber, from the Brown County Library, said it wasn't clear from census records whether Heynen had even graduated from high school. And yet, the president of the United States selected her to serve him personally, all before the age of 21.

The long battle to gain recognition

After serving as Wilson's private operator in France, Heynen moved back to Green Bay as a married woman to Albert Gerard, an American soldier who'd also served in the AEF frontlines. They had a daughter named Yvonne and moved to Los Angeles in 1929.

The trail doesn't exactly run cold after that, but it isn't clear from the records when Heynen died. She married at least three times, changing her name from Gerard to Swanson to Marcel. Yvonne, her daughter, played a bit part as a dancer in the 1933 film "Flying Down to Rio."

But what is clear is that Heynen wasn't alive by 1977, when President Jimmy Carter finally recognized the Hello Girls as veterans. It took 60 years of continued effort by many, including Hello Girls veteran Merle Egan Anderson of Montana and the former Maine congressman, U.S. Rep. Edward Moran, who died in 1967 — a decade before its success. At 91, Anderson received her honorable discharge as a veteran alongside the two surviving veterans, Marjorie McKillop, 81, and Alma Hawkins, 89.

Timbie, the granddaughter of Grace Banker, recognizes how long these things take. After all, Timbie is 60 years old, which also represents the time it took for her grandmother and the other 222 women to gain veterans status: "Imagine! That's my entire lifetime that these women waited."

The battle for more adequate recognition continues, but it does have a deadline, Timbie said. The Hello Girls group has until the end of the congressional year, which is technically early 2025.

"The Hello Girls' families should know who they were and what their service was," Timbie said. "I speak for all of us descendants, I'm sure, but the immense pride we have for our grandmothers and great-aunts is immeasurable, and to see their story come through, I would just be so honored and humbled."

Timbie encourages readers to reach out to their state representatives and senators to support the Hello Girls Congressional Gold Medal Act of 2023. To find the status on your state, head to the Hello Girls Gold Medal website.

Natalie Eilbert covers mental health issues for USA TODAY NETWORK-Wisconsin. She welcomes story tips and feedback. You can reach her at neilbert@gannett.com or view her Twitter profile at @natalie_eilbert. If you or someone you know is dealing with suicidal thoughts, call the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline at 988 or text "Hopeline" to the National Crisis Text Line at 741-741.

This article originally appeared on Green Bay Press-Gazette: 4 Wisconsin women served in WWI as Hello Girls; a fight continues on their behalf