Who is at greatest risk of fentanyl death in Tri-Cities? Overdose stats paint a profile

The Tri-Cities victims of the fentanyl epidemic probably aren’t who you think. And those misconceptions are costing lives.

The lethal opioid is pushing the Tri-Cities toward a grim milestone — 500 overdose deaths in eight years.

Information about the people dying from drug overdoses in recent years paint a picture of who are at the highest risk of falling victim to the deadly drug.

A Tri-City Herald analysis of Benton Franklin Health District data shows it’s often a man in his 40s or 50s, working in construction, trade labor, the food service industry or healthcare.

He most likely graduated high school and sometimes attended college or a trade school.

Tri-Cities victims usually aren’t homeless, though there is a good chance he lives alone — possibly contributing to his death.

Out of nearly 400 Tri-Citians who died from overdoses from 2016 to 2022, only 32 people (8%) were listed as unemployed or disabled.

Just a handful of those who died last year were listed as homeless by our county coroners.

Merit Resource Services Executive Director Shereen Hunt said that whether we realize it or not, we all know someone struggling with addiction, and helping them find a path to recovery could save their life.

“Every single one of us in our community, we all know someone,” she said. “Either a family member or a friend who is having problems in their life because of drug and alcohol use, it impacts everyone. It impacts their families, our criminal justice system, our hospitalization rates. It impacts everything.”

For Yvonne Lakey, Merit’s lead Recovery Navigator, family encouraging her to get into recovery was life saving and life changing.

Now she tries to meet people struggling with addiction where they are, whether it’s a walk-in at one of their offices or when they’re booked into jail, in order to help them start on the path to recovery.

“Everyone has situations in their life, past trauma. This isn’t the life they want to have,” Lakey said. “If they want to make that change I want to help them get there.”

Record high fentanyl deaths

Tri-Citians are dying from overdoses at more than twice the rate they were just five years ago.

For the second year in a row, 2023 saw the Tri-Cities reach a new record with fentanyl-related deaths in Benton and Franklin counties.

About 70 people died of overdoses or medical issues tied directly to drug use last year.

At a rate of about 9-in-10, fentanyl or fentanyl combined with other substances was the primary driver of these deaths.

Only 8 of 65 overdose deaths were caused by drugs other than fentanyl, according to preliminary data from the coroners in Benton and Franklin counties.

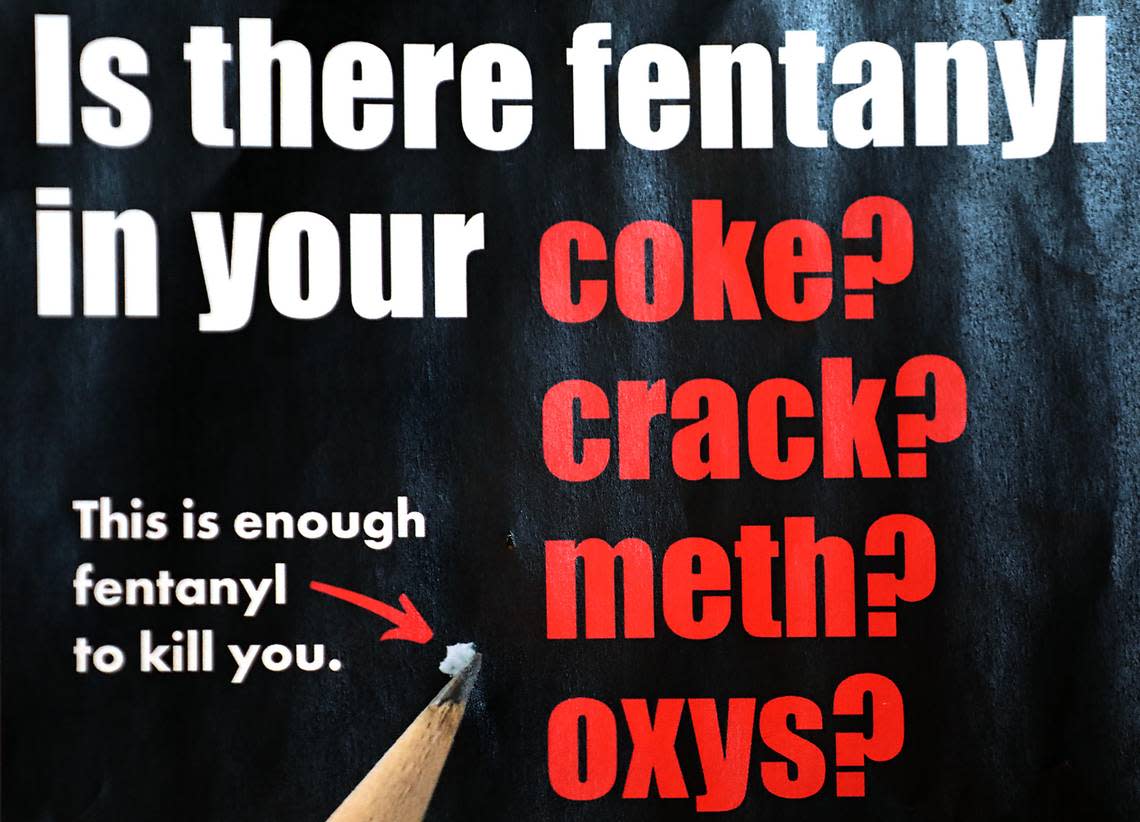

Fentanyl is a synthetic drug that is 100 times more potent than morphine and hundreds of times stronger than street-level heroin, federal officials have said.

About two-thirds of the victims who died from overdose-related deaths in 2023 were at least 40 years old. Only 10 were younger than 30.

That includes at least two children and a 16-year-old whose deaths are believed to have been caused by the deadly opioid.

The death of a 1-year-old girl in Franklin County is still under investigation.

And a 4-year-old girl in Kennewick that police believe died from ingesting fentanyl while her parents were in a motel bathroom allegedly getting high. Toxicology results for 4-year-old Ryleigh Walker have not yet confirmed she died from fentanyl, but investigators say partially intact fentanyl pills were found in her stomach and in her nose.

Statewide, the crisis has gotten so severe that in 2022, nearly 1-in-12 emergency calls for injuries were related to suspected overdoses in Washington.

The state estimate is in line with regional numbers, according to data from the state Department of Health and community health organization Greater Health Now. However not all ambulance services participate in data collection.

Greater Health Now is region wide and also includes Yakima, Kittitas, Whitman, Walla Walla, Columbia, Garfield and Asotin counties.

The Benton Franklin Health District said the EMS calls in our region are likely lower than the state’s estimate, lining up more closely with Tri-Cities emergency department visits related to suspected overdoses, which was at 2% for the last quarter of 2022 and 3% for the year.

Kadlec Regional Medical Center in Richland sees more than 100,000 visits to its ER each year, according to a 2017 state Department of Health estimate.

If 3% of all visits were overdose related, that would average 8 each day.

During the same period, nonfatal overdoses in Benton and Franklin counties accounted for about 9% of all injury hospitalizations, and more than a quarter of all injury deaths in the Tri-Cities area.

That means 1-in-11 injury hospitalizations are being linked to suspected overdoses.

But in the Tri-Cities, and across Washington, overdose hospitalizations remain on a downward trend, while overdose deaths continue to tick upward.

The reason goes back to the likelihood of victims living alone with no one to call for help.

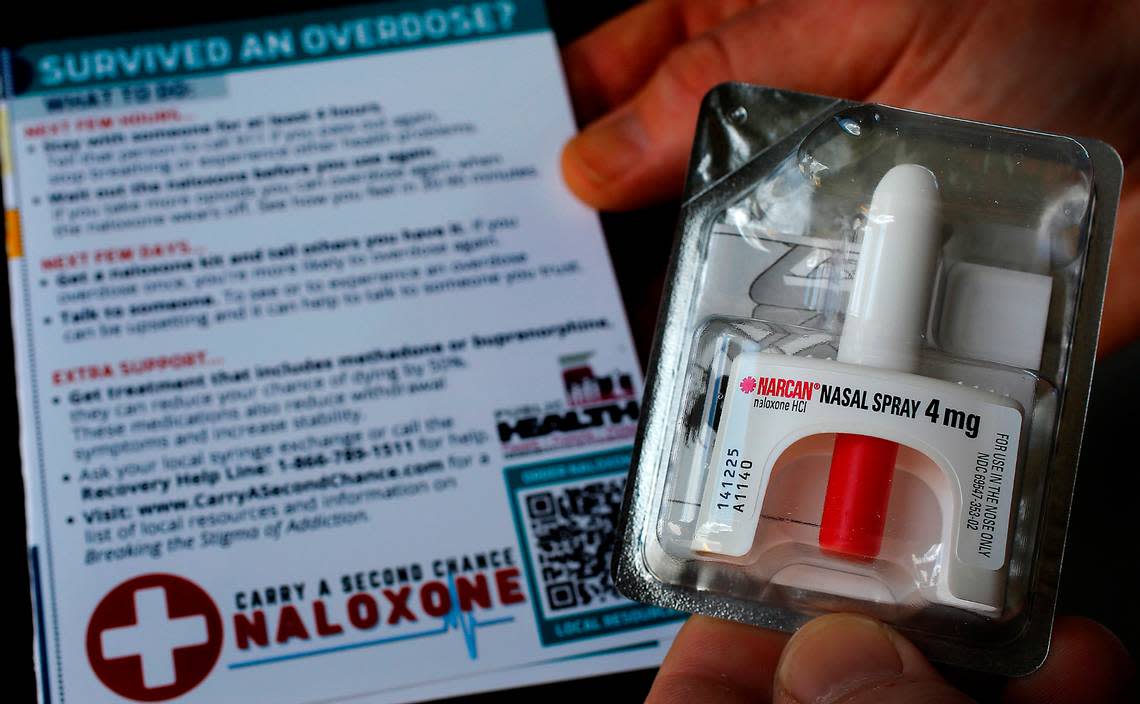

If an EMT responds to an overdose call, they can administer Narcan, or naloxone, which reverses overdose symptoms and greatly improves the person’s chance of survival, leaving those using fentanyl at home alone at much greater risk.

What can be done?

Education and access to naloxone are two key ways to help reduce fatal overdoses, Hunt told the Herald.

Hunt said people struggling with addiction need education to make them better aware of how much more dangerous fentanyl is than many other drugs and to stress the importance of having ready access to naloxone to help reverse overdoses.

Gov. Jay Inslee is making it a priority this year to increase funding for education in schools across Washington and recently announced the rollout of a new program to put naloxone on every school campus.

The health district told the Herald they are looking into what it would take to get the Tri-Cities to “naloxone saturation” or a high enough distribution of the life-saving drug to ensure it is available whenever needed.

Their early estimate is that the Tri-Cities would need 3,964 kits in circulation, or 1,270 per 100,000 people.

The American Medical Association has said there is a correlation between the decline in prescription opioid use after tougher laws were passed and the rise in fentanyl use.

Fentanyl is often mixed in with various other counterfeit prescription medications or illicit drugs, leaving many users unaware of its presence until they become hooked or accidentally overdose.

The problem has become so widespread that a Los Angeles Times investigation last year uncovered fentanyl and methamphetamine in Adderall and opioid pain medications coming from legitimate pharmacies in Mexico.

Hunt said fentanyl use, like heroin, comes with severe withdrawals, leading many people to continue using just to stave off the symptoms. They may not have even known they were taking fentanyl until it’s too late.

“Their goal is to get high or alleviate those severe withdraw symptoms, not to die,” she said. “It’s a fine line between ‘the next time I use am I going to get high enough or go over the line and not wake up?’ It’s like Russian roulette.”

Hunt said that while education and naloxone can save lives in the short run, with continued fentanyl use, the longer it goes on, the higher their risk of dying becomes.

A journey to recovery

Merit performs intake surveys with new patients and immediately gives them a naloxone kit if they indicate they’ve used fentanyl. Hunt said they stress the danger of using alone at home. Then they work with the patient to help get them a formal substance use disorder diagnosis in order to begin medical treatment.

Medications such as suboxone, or buponephrine, have been shown to increase the likelihood a patient is successful in recovery, and can cut the chances of fatal overdoses in half, according to the National Institutes for Health.

Inslee is also pushing for expanded funding for Oxford House Recovery Homes, which are community-based mutual help residences for high-risk individuals. They help people struggling with addiction stay clean, find work and offer ongoing support.

Last year Merit launched its Recovery Navigator Program, which pairs peer specialists with patients to help guide them in their recovery journey. These peer specialists are people who have been successful in their own addiction recovery, and can relate to the fears or struggles a patient might be experiencing.

Lakey said that five years ago she wouldn’t have believed you if you told her that she’d one day be leading an entire team of people in recovery as they helped others survive and overcome their own addiction issues.

“I am a recovering addict, I believe everyone deserves a second chance” she said. “My grandfather is the one who, when my life was turned upside, gave me a second chance ... Really being able to give back what was given to me really helps me in my recovery.”

Lakey said that her own recovery journey has transformed her life and relationships, and she wants to help others do the same.

“I am truly grateful for what I do, I’ve been able to go back and mend relationships in my life and go back and thank the law enforcement officers who gave me the push I needed,” she said. “My grandfather passed, but before he passed away he was able to see me clean and sober for over two years. He was a big person in my life.”

Lakey said she’s also been able to build a relationship with her father who has had similar struggles and now they’re closer than they’ve ever been. She said she’s grateful every day that she has a relationship with her children and that her grandchildren will never have to see her struggle with substance use.

Lakey said her own struggles help her build bonds with people in recovery, and help them see that getting their life back is possible.

“It’s a good feeling, it’s definitely a good feeling knowing that somebody is willing to possibly turn their life around, and follow the recommendations,” she said. “It’s a new journey, just knowing I’m going to be able be part of that is (fulfilling).”

Lakey said that whether you are struggling with addiction or it’s a loved one who needs assistance, the most important thing you can do is reach out and ask for help. She recommends 12-step treatment programs like Narcotics Anonymous, which also has support groups for family members.

“You don’t have to go through this alone,” she said. “None of us wanted to grow up and be an addict. It’s not something we chose and I think that a lot of people don’t realize that.”

Hunt said that access to help has improved greatly, and if someone is looking for help with addiction, they can get them started on a program right now.

“I think the biggest thing we can do is to let them know that help is available, there is access to treatment. We don’t have a waiting list, we don’t have a capacity problem,” Hunt said. “There are empty beds right now, it’s just a matter of getting their assessment.”

“If we can get them in the door and start the process, that’s the biggest hurdle, and that’s where the recovery navigator peers come into play to help them.”