How a new grassroots movement aims to reform Oklahoma's criminal justice system

A grassroots movement in Oklahoma is underway to reshape criminal justice by improving crime prevention programs and developing better alternatives to incarceration, supporters say.

Faith leaders, social workers, attorneys, tribal officials and nonprofit organizations want to change long-standing beliefs about crime and punishment.

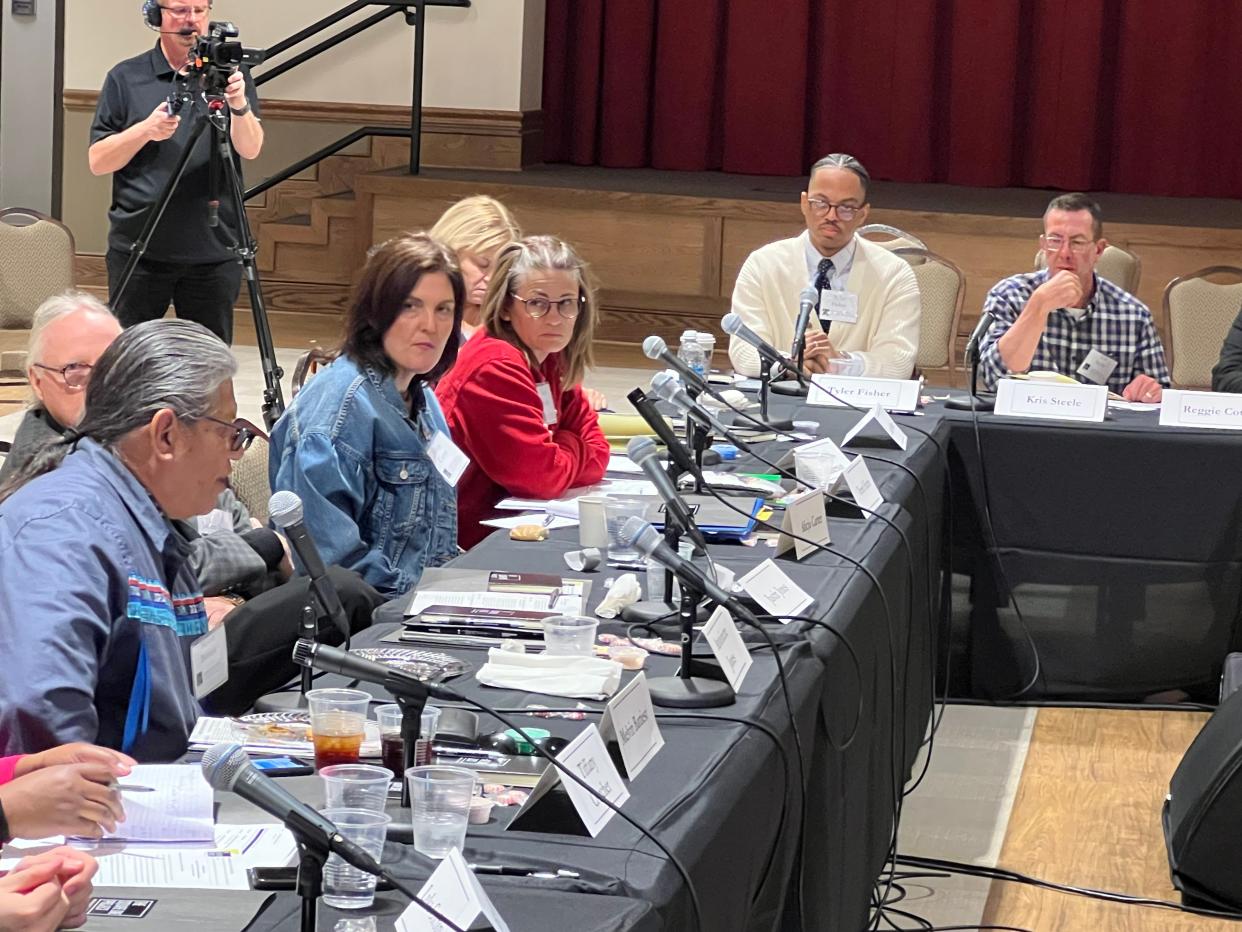

A recent Roundtable Justice and Values discussion was the culmination of meetings across the state that began nearly two years ago to review state law and gather public feedback to create better policies. The group plans to urge the Legislature to adopt new proposed legislation to reform the justice system, attendees said.

Kris Steele, The Education and Employment Ministry executive director, said the goal is to change public perception that incarceration is the only way to satisfy justice. His nonprofit works to help people transition from prison back into society.

“This is an invitation to reimagine our approach to justice,” Steele said. “The end result is to develop a strategy to change the culture in Oklahoma, to change the narrative in our state as it pertains to how we collectively think, feel and act toward people in the criminal legal system.”

Oklahoma has historically had one of the highest incarceration rates in the world

Steele said Oklahoma’s policy to prioritize incarceration keeps the incarceration rate too high. Historically, Oklahoma has held the highest incarceration rate in the world and the nation. A recent report shows it has dropped to the fourth-highest following decriminalization of some nonviolent offenses, but it’s rising again. According to the U.S. Bureau of Justice Statistics, 6% more people were admitted to state prisons from 2021 to 2022.

To better understand the reasons people commit crime, Steele said the group examined experiences that led to their incarceration.

“It’s just been a real moment of truth to say, why aren’t we asking them what they may have needed to avoid engaging in activities outside the social norm, to break the law?”

The group’s discussions on possible alternatives to prison have included programs like Common Justice, said Square One’s community partnerships director, Anamika Dwivedi. Square One is an initiative of Columbia University’s Justice Lab that facilitates community discussion on alternatives to incarceration.

More: Jail trust approves $750K deal with sheriff to cover cost of transporting detainees

The model allows a crime victim to hold the offender accountable and restore justice without incarceration, she said.

The program is used in Brooklyn and the Bronx to facilitate agreements between violent offenders and victims. The offender must complete the recommended plan to restore justice to the victim.

“It is a restorative process to respond and deal with harm when it happens,” she said. “They work with all of those involved in the harm to find a way outside of incarceration to restore justice.”

There is support for such programs in Oklahoma among some prosecutors if it enhances public safety and “makes the victim whole,” said Chris Boring, president of the Oklahoma District Attorneys Council.

“It’s not a perfect system we have today, by any means,” he said of the criminal justice system. “I think prosecutors, judges, defense attorneys and counselors are all in, all trying to figure out what is the best way to keep communities safe?”

Could neighborhood groups work to respond to some crimes? A case study in Brooklyn

Sen. George Young, D-Oklahoma City, who serves on the criminal justice reform group’s steering committee, said he hopes to see support for reform in the Legislature.

He touted an initiative in Brooklyn where neighbors responded to low-level crimes in a two-block area. The Brownsville Safety Alliance is a team of residents, police and district attorneys who work to prevent crime and reduce prosecutions leading to prison sentences. Its members do not have arrest powers, but have resolved criminal complaints like shoplifting, domestic violence and the surrender of illegal weapons without arrest.

“I think those are the kinds of things we want legislators to hear so that they’ll see their jobs differently,” Young said.

The Justice Lab plans to publish a report of its findings early next spring.

Oklahoma Voice is part of States Newsroom, a nonprofit news network supported by grants and a coalition of donors as a 501c(3) public charity. Oklahoma Voice maintains editorial independence. Contact Editor Janelle Stecklein for questions: info@oklahomavoice.com. Follow Oklahoma Voice on Facebook and Twitter.

This article originally appeared on Oklahoman: Grassroots group wants reform as Oklahoma ranks high in incarceration