His grandfather was an Italian POW at Ft. Lewis. He’s here to trace his journey and say goodbye

Andrea Franzoni is on a journey that’s taking him through the western United States by bike and backward in time.

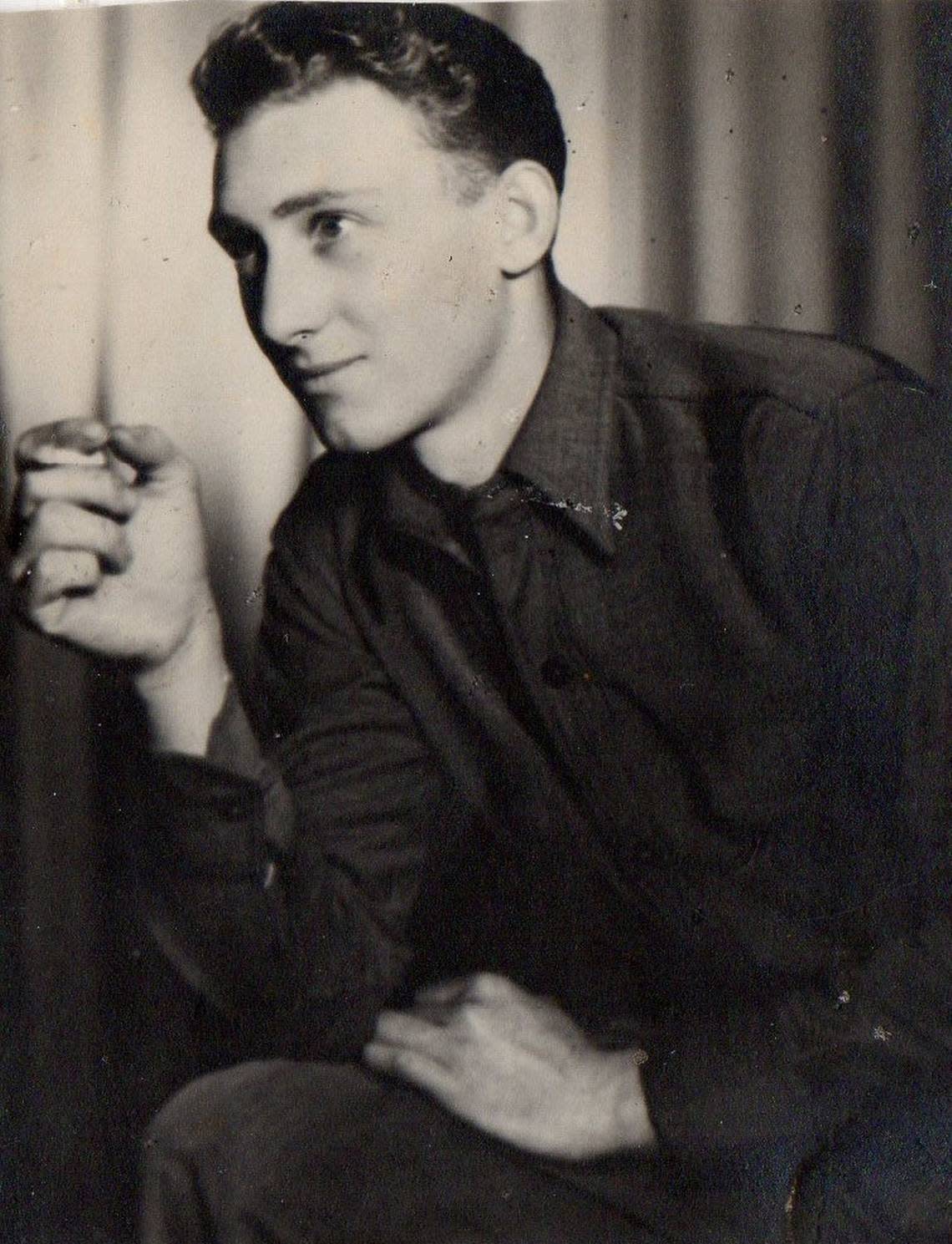

The 32-year-old Italian had never set foot on American soil until a few days ago. But his grandfather had — as a prisoner of war at Fort Lewis (now Joint Base Lewis-McChord) in the 1940s.

Aldo Arrighi’s time as a POW was filled with adventure, love and terror, he told his grandson. It had a life-long impact on him. Arrighi, in turn, had a profound impact on Franzoni as he grew up at Lake Garda, in Northern Italy.

Years before that, the pair had entertained the idea of returning to the places he had been held as a POW, particularly at Fort Lewis. Arrighi often recounted the majesty of waking up to Mount Rainier.

But Arrighi died in 2019 at age 97.

“He was too old,” Franzoni said. “And he was always afraid of being a disturbance to other people.”

Now, Franzoni is on a quest via bicycle to retrace the route his grandfather took as a POW and to visit the camps where he was held from Seattle to Arizona. It is, he said, a way to close unfinished business with his grandfather.

“The main reason I want to visit those places is just to walk on the same soil that grandpa used to work on,” Franzoni said.

Cycling under the Tuscan sun

At a glance, Franzoni’s quest might seem quixotic. There’s little trace of the buildings and man-made sights that Arrighi would have seen. Following the routes Arrighi took as a POW as he was transferred from camp to camp are, at best, approximations.

But, Franzoni said, that’s not his main goal.

“It’s a way to close your memory, a good way to say goodbye,” Franzoni said as he settled in for a break at Siena’s famous piazza, or town square on a sweltering day in mid-July. Nearby, crews were setting up for an open-air opera performance.

Franzoni had just biked 225 miles over two days to reach the ancient, hilltop city in Italy’s Tuscany region. He passed miles of olive orchards, crossed the Ponte Vecchio — Florence’s famous covered bridge — and paused at an American cemetery where 4,392 U.S. military personnel killed in World War II are buried.

The idea for the journey down the western U.S. began in the summer of 2020 while Italy was getting hit hard by the COVID-19 pandemic. Franzoni purchased a bike trainer. The device’s video screen can display routes all over the world.

He chose to bike, virtually, the roads between Florence, Arizona and Tacoma, where Arrighi began and ended his imprisonment.

“It was a chapter I wanted to close,” he said. When he finished, he knew that only biking the real route would provide closure.

Grandpa Aldo

When Franzoni was a boy, Grandpa Aldo was just the fun old man with a lot of long stories.

“It was the Sunday afternoon story,” Franzoni said. “After lunch. It was like, here we go again.”

But when Franzoni turned 16 and with adulthood bearing down on him he began to see his grandfather’s life through the eyes of a young man with all the attendant responsibilities and uncertainties.

“All the weight that he had on his shoulders,” Franzoni said. “He became a person I looked up to.”

It was a life forged by hardship and war. Arrighi’s mother had died while he was still a boy and his father, ostracized for being an anti-fascist, would die soon after World War II.

Nations at war

Italian fascist dictator Benito Mussolini entered World War II as an ally of Germany in June 1940. Arrighi was conscripted into the army in 1942 at age 21. It was a cause he and many others didn’t believe in, Franzoni said. But, you were either with Mussolini or suffered the consequences.

Arrighi was sent to North Africa where, Franzoni said, Arrighi wasn’t an enthusiastic soldier.

“He totally never got along with the politics of Mussolini,” Franzoni said. “His father, Antonio, was black-listed because he rejected to be a fascist. Nobody wanted to give him a job.”

One day, Arrighi was tasked with riding on the back of a motorcycle while unspooling a communication cable across a battlefield. At one point, he fell off the motorcycle, which kept going, and Arrighi had to run across the field to safety while still playing out the wire as an impatient Italian general waited.

Food and supplies were scarce. Morale was low. Arrighi and his fellow troops surrendered to Allied forces in the Tunisian city of Sfax in May 1943.

It was the beginning of the end for Italian forces in northern Africa. Italy fell to the Allies in 1945, and Mussolini was unceremoniously executed by his own people after trying to flee the country.

But with Italy still an enemy in 1943, Arrighi and his fellow POWs were first sent to Fort Eustis in Virginia and then POW camps in Florence and Papago, Arizona.

According to the Arizona Daily Star, the Italian POWs at Camp Florence were easy-going, sang while they marched and performed operettas in their spare time.

The camp made such a favorable impression on Arrighi that he later named his daughter, Franzoni’s mother, Flora — only after an Italian bureaucrat said no to Florence.

After two or three months in Arizona, Arrighi was sent to Fort Lawton in Seattle for labor duties. Today, the fort is part of Discovery Park in the city’s Magnolia neighborhood.

Privileges

The Italian prisoners were given privileges at Fort Lawton, including the ability to wander around Seattle, that seem generous by today’s standards. Their lenient treatment stirred resentment in Black soldiers at the fort. The Italians could enter stores and bars and see movies that the Black soldiers were barred from.

They could also date white women, something Black soldiers could not do.

Arrighi met an American woman, Eileen Larcher. The pair began dating, and her parents grew fond of Arrighi.

Although Larcher is now dead, Franzoni tracked down her nephew, Bainbridge Island resident Mark Julian.

Julian doesn’t recall his aunt mentioning Arrighi, so he was stunned when Franzoni first contacted him in 2015.

“My first thought was, ‘is this real?’ ” Julian said. “But, he knew details.”

Julian, 69, grew up in an extended Italian-American community in Seattle with family and friends, including Clemente “Menta” Tononi.

Tononi, an immigrant, befriended the young Arrighi in Seattle. It left a life-long impact on him, Franzoni said.

On Aug. 10, Julian gave Franzoni a tour of Fort Lawton.

“He obviously had really strong feelings for his grandfather and really wanted to do something to honor him,” Julian said. “That’s pretty impressive.”

Julian also took Franzoni to Seattle’s Calvary Cemetery. They were looking for family and Tononi’s graves.

Franzoni and Julian found Tononi’s interment niche in a mausoleum.

“Mark was nice enough to leave me there for a couple of minutes,” Franzoni said. “I just closed my eyes and say a prayer to him. And it was a quite an emotion.”

It was emotional for Julian as well, visiting long gone family and friends.

“Menta … and my grandparents were a big part of my growing up,” Julian said.

A riot and murder

On Aug. 14, 1944, tensions reached a boiling point at Fort Lawton and the Black soldiers attacked the Italian POWs. Arrighi told his grandson that he hid in a patch of stinging nettles to escape the violence.

“He was so scared,” Franzoni said of his grandfather. “He thanked God that he was still alive.”

Other POWs hid in creeks and woods.

“They did their best to cover from stones that were thrown at them,” Franzoni said.

“The problem is that no guards intervened that night,” Franzoni said. “It’s like they turned their back on the Italian people.”

The next morning, one of the Italian POWs, Guglielmo Olivotto, was found hanged.

A court martial led to the conviction of 28 Black soldiers, two for murder. Only in 2007, when documents were unsealed, was a lie-filled cover-up and miscarriage of justice discovered.

Resentment was building in white soldiers, too, in 1944. They egged on the Black soldiers to attack the Italians, it was later learned.

The Army was under pressure to convict. Any mistreatment of foreign POWs in American hands could lead to repercussions against American POWs in Germany and elsewhere.

The rushed convictions violated judicial norms.

In 2008, all 28 convictions were overturned, an apology was issued and back pay was given to the soldiers’ families.

Fort Lewis

Sometime after the riot, Arrighi was sent to Fort Lewis.

While Fort Lewis housed around 4,000 German POWs, according to journalist and historian Steve Dunkelberger, Arrighi was part of the much smaller Italian group.

For the rest of his life Arrighi would tell of being awestruck by Mount Rainier, which he could see from the POW barracks located near today’s Gray Army Airfield on Joint Base Lewis-McChord.

One day, Arrighi was ordered to wash Gen. Douglas MacArthur’s car at Fort Lewis. It was a highlight of his time there, Franzoni said.

Arrighi was discharged from Fort Lewis in October 1945, a few months after World War II ended in Europe. It took five months for him to travel across the U.S., the Atlantic and a war-torn Europe before reaching his home at Lake Garda.

Arrighi met his wife, became an electrician and never strayed far from home again.

Return to Fort Lewis

On Aug. 13, Franzoni visited the Lewis Army Museum. Later, Kanya Praetorius with JBLM’s public affairs office took Franzoni to where Arrighi would have been housed and to one of the base’s main gates from the WWII era, which is no longer in use.

As he walked where some buildings remain from that era, Franzoni was silent. Later, he said he had a frog in his throat, using the phrase to describe his emotions.

“It felt more like a pond of them,” he said.

The visit allowed Franzoni to close the only chapter of his grandfather’s life that had been left unfinished.

“I know that the people that die are not over there or down there,” Franzoni said pointing up and down. “They’re just inside. So, I tried to connect with grandpa and say, ‘Hey, we’re here. We did it.’ ”

The visit to JBLM was the high point for Franzoni and a counterpoint to Fort Lawton.

“Fort Lawton was a dark page of grandpa’s history because it left a big trauma,” Franzoni said. “He couldn’t get past it.”

Journey

Franzoni knows he won’t be able to trace the exact route between Arizona and Fort Lewis Arrighi would have traveled by troop train as a POW. But he’s studied railroad routes and roads and plotted a course as close as he can through Oregon, California’s Central Valley and east to Arizona.

Although his grandfather went from Arizona to Washington in the 1940s, Franzoni is making the trip in the opposite direction to take advantage of cooler desert weather in October.

A network of volunteers have arranged to house him along the way. In some areas, he’ll camp. He figures he’ll average about 40 miles per day on his hybrid road/mountain bike.

He’s gotten a mix of responses so far on his journey. Some find his quest inspiring and follow his trek on Facebook. Others just look at him quizzically, he said.

He had made it to Portland as of Thursday.

His trip will end at the site of Camp Florence, the place that inspired Franzoni’s mother’s name. Today, nothing remains of the camp except the soil Arrighi once walked on.