When governors like DeSantis run for president, history shows it’s a tough juggling act

One afternoon late last month, Ron DeSantis the governor and Ron DeSantis the presidential candidate were theoretically doing two different things at once.

His office announced he had signed eight bills — then shared paperwork that was filed at the same time DeSantis was headlining an event in a barn more than 1,000 miles from Tallahassee in Pella, Iowa. (His office later clarified that DeSantis signed the bills “prior to filing.”)

Historically, serving as governor has been the most popular path to the presidency. But recent history shows that sitting governors who’ve mounted national campaigns have struggled. Not one has been elected since 2000.

Their experiences offer a preview for what Floridians might expect and lessons for what DeSantis should avoid as the buzz of his campaign announcement is replaced by the grueling months of handshakes, donor dinners and state fairs. He is the first sitting Florida governor to run for president.

READ MORE: When is DeSantis governing vs. campaigning? The line — and the ethics — can be blurry

Already, DeSantis has been repeatedly criticized for his political ambitions. Watchdog groups and Democrats have filed complaints accusing him and his allies of violating campaign finance law or illegally blurring the line between official duty and the political operation.

DeSantis will have to carefully manage his schedule as well as lean heavily on allies while he’s away to avoid looking like he’s not focused on Florida, political experts said.

“Gov. DeSantis remains serving the people that he was elected to serve,” said Jeremy Redfern, a spokesperson for the governor’s office, before listing some of DeSantis’ actions last week, including signing dozens of bills and announcing that Florida was suing the Biden administration over college accreditations.

If other campaigns serve as any warning, DeSantis will have to retool the game plan he used in his landslide statewide reelection bid to recognize that what worked in Florida is not guaranteed to resonate in other corners of the country.

“You think it’s difficult or challenging to run a big, diverse, dynamic state,” said Ray Sullivan, who served as chief of staff to former Texas Gov. Rick Perry and worked on the campaign teams for Perry and George W. Bush, another ex-governor. “Running for president is a lot more difficult.”

The governing vs. campaigning balancing act

Then-Gov. Chris Christie spent 261 days in 2015, or 72% of the year, in states other than New Jersey while he ran for president in the 2016 cycle, according to a Wall Street Journal article from the time. He spent 56 of those days in the early primary state of New Hampshire.

Patrick Murray, director of The Monmouth University Polling Institute in New Jersey, said these absences plus a drop-off in Christie’s policy proposals in the state led his constituents to sour on him, and his approval began to “tank.”

“There was a sense that now that he had decided to run for president, he didn’t need New Jersey anymore,” Murray said. “[People felt] there was a vacuum in the state because he basically had ceded running the state government.”

Ben Dworkin, director of the Rowan Institute for Public Policy and Citizenship at Rowan University in New Jersey, said any angst against Christie at the time was exacerbated by his running for higher office, a danger that DeSantis may also face.

In the month since he formally jumped into the race, DeSantis has spent at least half of his days in states other than Florida.

“In Gov. DeSantis’ situation, there will be daily coverage of him in Iowa or New Hampshire ... then it’s going to become noticeable,” Dworkin said. “And anytime somebody has a complaint, it’s going to be magnified because [they can say]: ‘And that guy’s not even in town doing his job.’ ”

DeSantis’ packed political calendar has already limited his visibility in Florida. In one week this month, he stopped in Nevada, California, South Carolina and Washington, D.C. Typically after the legislative session, DeSantis would hold near-daily news conferences to tout bill signings or state-funded projects. Instead, he’s recently signed several high-profile bills in private — including a law allowing people to carry guns without permits and even a tax break package that DeSantis frequently mentions on the campaign trail.

Several political experts emphasized that while the public generally tolerates some absenteeism during major campaigns, governors must be in their state anytime a disaster or major controversy strikes. DeSantis got a taste of this when he traveled out of state, and then abroad on an international trade mission, just days after Fort Lauderdale endured record flooding in April.

“Fort Lauderdale is under water and DeSantis is campaigning in Ohio right now instead of taking care of the people suffering in his state,” Donald Trump Jr. wrote on social media at the time.

DeSantis “took a 19 hour flight to Japan, but couldn’t take a 1 hour & 50 min flight to Fort Lauderdale,” state Sen. Shevrin Jones, D-West Park, tweeted.

Bill Miller, a longtime Texas lobbyist, referenced U.S. Sen. Ted Cruz’s infamous 2021 trip to Cancún, Mexico, while an ice storm killed more than 240 Texans — saying that if Cruz had been a presidential candidate at the time (as he was in 2016), it would have been an even bigger scandal.

“If you’re missing in action, it could be a mortal wound,” Miller said.

Political takeaways

When governors become presidential candidates, added scrutiny is applied to all their official actions, political experts said.

The day after DeSantis announced his presidential candidacy alongside Elon Musk on Twitter, he signed a bill into law that will protect companies like SpaceX from liability if space flight passengers or crew members are injured or killed — prompting a wave of news stories making the connection. (SpaceX and Twitter are both owned by Musk.)

Top aides in the governor’s office also recently solicited donations from lobbyists to DeSantis’ presidential campaign, an apparent breach of the line that traditionally separates government and political campaigns. At the time, the governor had not yet approved the budget, meaning projects that would benefit the lobbyists’ clients were still at the mercy of his veto pen.

DeSantis has defended his staff, saying they made the asks “in their private time” and did not use state resources.

“You have to be doubly careful,” said Miller, the Texas lobbyist. “That’s the difference. It’s not [just] about the candidate, it’s about the governor and the candidate.”

Another political lesson that has been made clear by past governors’ presidential campaigns: The strategies that help a candidate win their statewide elections don’t always transfer to national success. Because of that, the appropriate political response to a particular issue in a governor’s home state might be in conflict with what the Republican base nationally wants to hear, experts noted.

DeSantis appears well aware of that. When he’s in Iowa, DeSantis emphasizes Florida’s new law banning most abortions after six weeks — a noticeable departure from his reelection campaign in Florida, when he repeatedly dodged questions about abortion. (Polling shows Floridians generally support access to the procedure, but evangelicals are a key Republican voting bloc in Iowa.)

Cal Jillson, a longtime political science professor at Southern Methodist University in Dallas, said one moment of Perry’s unsuccessful 2012 campaign poignantly illustrated this political truth.

At a debate in New Hampshire, the candidates were asked what they’d be doing if they weren’t on stage that Saturday night. “I’d probably be at the shooting range,” Perry replied, in a response tailor-made to winning in Texas.

“People all around the country said, ‘What? I’d be watching movies,’” Jillson said.

While DeSantis, a native Floridian who wears cowboy boots with his suits, talks often about his successes in Florida, he has invoked other geographies to broaden his appeal. In his latest book, he wrote that his upbringing “reflected the working-class communities in western Pennsylvania and northeast Ohio.”

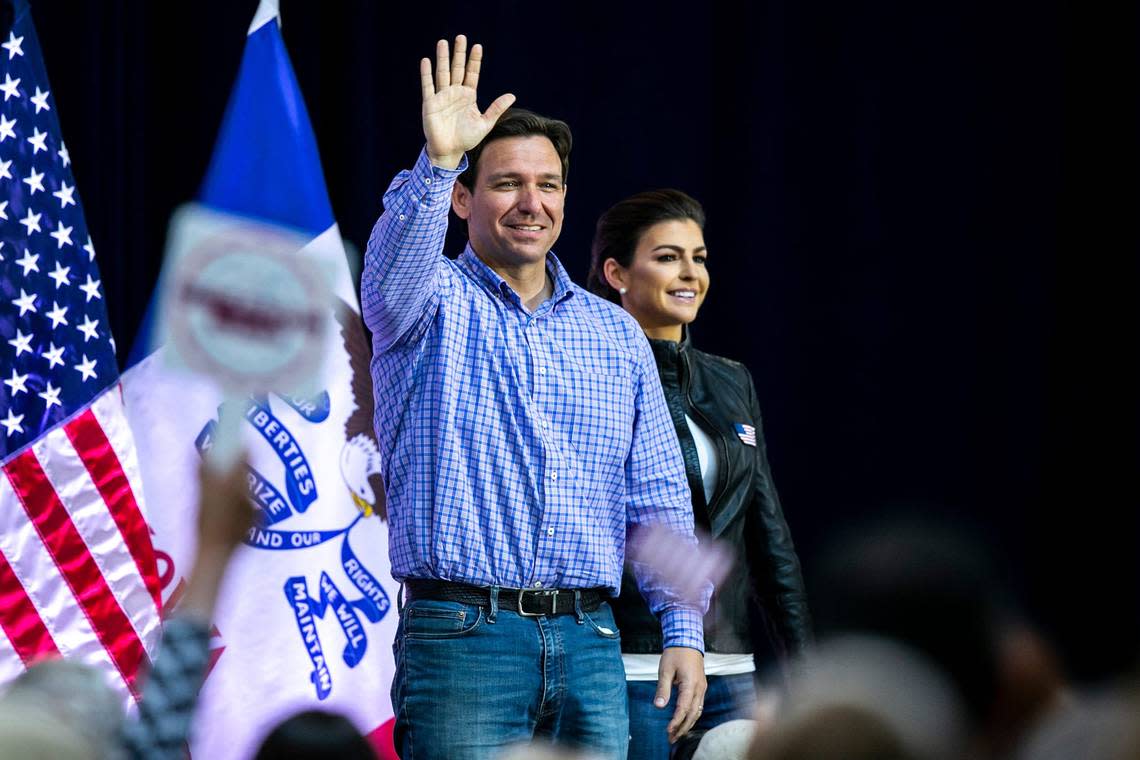

And when DeSantis kicked off his campaign in Iowa last month, he proclaimed that “Florida is the Iowa of the Southeast.” The line may have sounded familiar to anyone who’d heard his speech to a Utah Republican Party convention about a month earlier.

There, he told Republicans: “Florida is the Utah of the Southeast.”