Gov. DeSantis has enhanced, not weakened, African-American studies in Florida | Opinion

When White House press secretary Karine Jean-Pierre said last month of Gov. DeSantis, “When you think of the study of Black Americans, that is what he wants to block,” there was an easy way for reporters to test her assertion.

Just check the new English Language Arts standards that the Florida Department of Education adopted in February 2020. They’re called the Benchmarks for Excellent Student Thinking (B.E.S.T.), and they replaced the Common Core model of the 2010s. Everything in them belies Jean-Pierre and everyone else who accuses the governor of anti-Black bias.

The most significant innovation in the B.E.S.T. layout is the inclusion of a vast amount of literary history. We have many authors, lots of titles and literary periods, too (ancient Greece, Renaissance Period and Romantic Period, to name a few). The content is downright daunting, and it is exactly what American students need if their knowledge of history, culture and language is to improve.

The document organizes the material well — no mushy pile from which teachers grab-and-go inconsistently. Titles and names are grouped by grade level and within periods, and the periods themselves are given characteristic features. (I was a consultant on the project.)

The examples listed in the document are copious enough to tell us pretty closely what English teachers will place on their syllabi and discuss in class. Here are some names that a quick word search of the document retrieves: Frederick Douglass, Booker T. Washington, W.E. B. Du Bois, Langston Hughes, Zora Neale Hurston, Richard Wright, Gwendolyn Brooks, James Baldwin, Lorraine Hansberry, Alice Walker and James Weldon Johnson. In seventh grade, teachers are encouraged to assign “Freedom Walkers: The Story of the Montgomery Bus Boycott; in eighth grade, Nelson Mandela’s “Long Walk to Freedom” and Douglass’ “Blessings of Liberty and Education;” and in 12th grade, the poems of Countee Cullen.

The bare inclusion of so many African-American works and themes puts to rest the charge of educational racism. Note, too, that DeSantis initiated the B.E.S.T. project in January 2019, long before the current controversy over African-American studies started and before the George Floyd riots forced issues of race on politicians more strongly than at any time since the Civil Rights era. The B.E.S.T. initiative was not a political action or reaction. The governor wanted abundant literary history on grounds of principle.

The respect for Douglass, Du Bois, Richard Wright and others extends well beyond simple inclusion. The standards work on the idea that materials in the curriculum rightly belong in a holistic design, a canon. The works cited in the document together form a structure running from the ancients to the moderns, a lineage of great literary expression. Works don’t stand alone. They form, to use T. S. Eliot’s phrase, “an ideal order of monuments.”

This grants canonical authority to the titles on the syllabus. “These are the best, the works for the ages,” the tradition tells the students. When I was in grad school in the 1980s, “canon” was a bad word, showing a Eurocentric bias, and teachers set about breaking it up in the name of diversity. They didn’t produce a more diverse canon, though. They killed any canon at all. The B.E.S.T. standards reverse the slide. They make “Their Eyes Were Watching God” and the rest essential reading.

The new canon does more to preserve the past than does theory talk of systemic racism and white privilege. People remember things better when those things are concrete and fit into larger wholes. When Booker T. Washington’s memoir is placed in a tradition of American individualism and stories of success from Ben Franklin’s “Autobiography” forward, the book sticks in high schoolers’ heads more firmly. Teach the book by itself, disconnected from literary tradition, as is usually the case, and it dissipates soon after kids finish the term.

Chronology and canonicity are two effective forms of grouping and remembering. Courses in social justice and cultural relevance offered in schools of education across the state are of little help. We don’t need exotic notions of intersectionality informing high school pedagogy. We need, instead, the moment Douglass strikes back at Mr. Covey; Du Bois on the color line; “We real cool” and “We wear the mask;” a Renaissance in Harlem; the Invisible Man in his basement, Malcolm Little in his cell copying the dictionary . . .

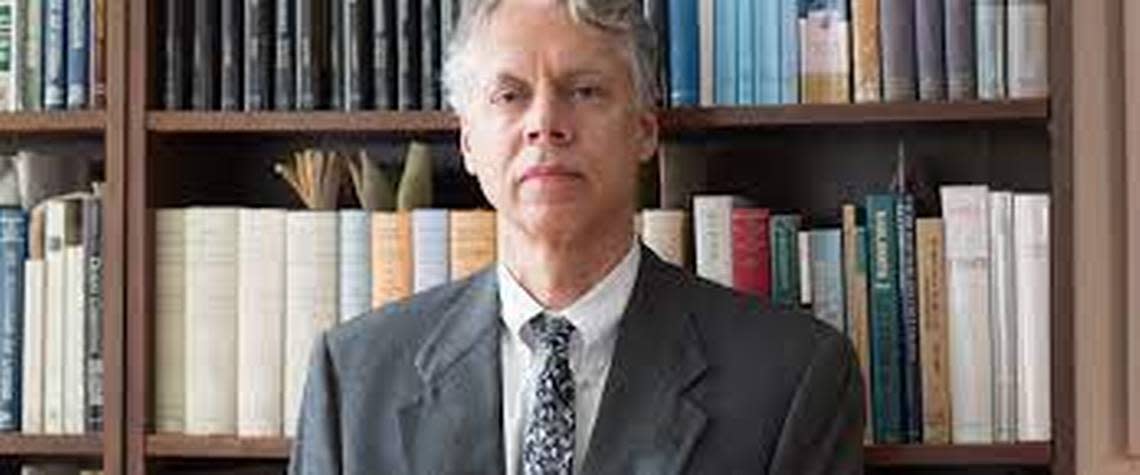

Mark Bauerlein is emeritus professor of English at Emory University and an editor at First Things magazine. He recently was appointed to the board of trustees of the New College of Florida.