The Glowing Facade of New York’s Perelman Performing Arts Center Almost Never Happened

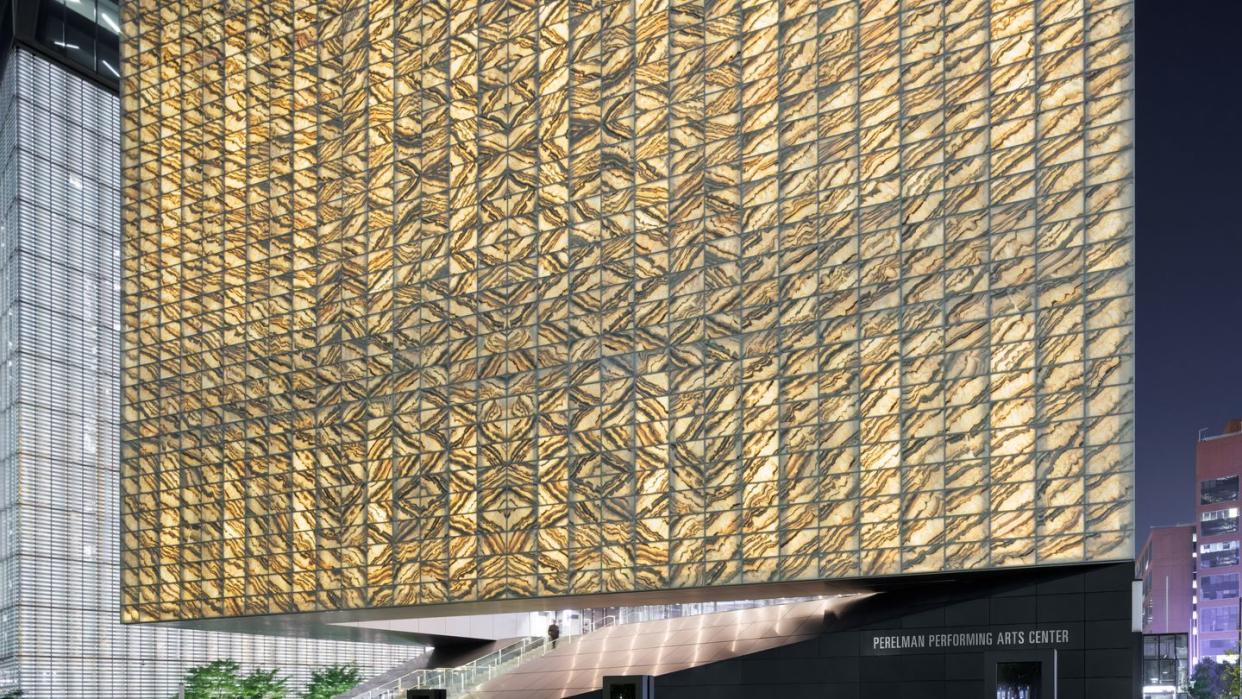

The Perelman Performing Arts Center, dedicated at the World Trade Center site in New York City today, is an architectural marvel—a floating cube with a translucent facade of patterned marble that glows like a light box at night. The striking design is so complex that even its architect did not know if he could pull it off. In an interview with ELLE DECOR to be broadcast later this month at the Marmorac marble and stone trade fair in Verona, Italy, the architect—Joshua Ramus of the New York–based firm REX, who worked on the design for nine years—shared the dramatic journey toward creating the $500 million, 129,000-square-foot arts center. “It was some combination of love and panic,” Ramus admits.

ELLE DECOR: The commission to design the Perelman Performing Arts Center was very significant for you personally, wasn’t it?

Joshua Ramus: Yes. I lived only a few blocks away from the World Trade Center site on 9/11, and so it had strong personal meaning to me. It is an extraordinary honor to design a performing arts center on that site. It was in the original master plan to use the optimistic aspects of art as a counterpoint to the commemoration across the street. Seeing it completed at this point is a very emotional experience.

ED: The building is situated across the street from the 9/11 Memorial & Museum. How did that location influence the design?

JR: It drove a lot of our thinking about the design. We wanted to do something that would be pure and elegant. During the day, it would have a kind of sobriety that is respectful of its context. But at night, the translucent marble facade glows and asserts a kind of respectful individuality.

ED: Everyone is talking about that unusual marble facade. How did you make that happen?

JR: It’s 12-millimeter-thick slabs of Portuguese marble. The stone has ferrous oxide, which renders the marble a cream color, as opposed to white. That gives the marble the quality of amber when you shine light through it. It also has vibrant gray veining, which we enhanced with a double crosscut technique, which makes it quite fragile. Now anyone who has ever had a marble countertop and spilled a glass of wine on it knows that marble is quite fragile. It draws water into it. To create a high-performance facade, we laminated the stone between layers of insulated glass.

ED: Why did you choose such a challenging material for the exterior?

JR: It’s a beautiful antidote to the severity and austerity of the building’s form. The marble is so alive and organic, and in a way humanistic. It would have looked too severe without it since the building is a cube. This stone is very warm, and the patterns are intricate. The more you stare at it, the more you see.

ED: And yet the design was very risky, wasn’t it?

JR: It was incredibly complex. The stone we wanted was from a very small quarry. There was a risk it might run out, or change [in appearance if it came from another spot]. Most people don’t notice but at the Washington Monument in D.C., there is a weird watermark about a third of the way up on the obelisk. That’s because of the Civil War. They started building it before, and when they came back after the war, the stone had shifted in color. And to make things even more difficult for us, because of the process of cutting the marble and laminating it, we had to commit to the composition of the first 20 percent of the facade before knowing what the rest would look like. With stone, you must book-match the pattern. It’s like a butterfly image or Rorschach. It needs to be symmetrical. So how could we be sure of a beautiful result [with only 20 percent of the stone]? The thing that saved us is that the veining throughout the quarry was very consistent. To compose the image, we created digital images of every tile.

ED: Did you have a Plan B in case it did not work?

JR: We had a design alternative from the outset, and to be honest we advanced both at our own cost, because we were the ones trying to persuade the client to do the stone facade. They always knew that if for some reason we hit a roadblock from a technical standpoint [and needed a backup], it wouldn’t be catastrophic to the project. At one point, the owner of the quarry called and said I needed to go to Portugal. He didn’t tell me why, and I was really nervous. I flew over and he drove me down a steep incline of mud into the quarry. It was extraordinarily beautiful. He stopped the car, pulled the emergency brake, and turned to me. “The quarry,” he told me, “she wants to do the job.”

ED: What inspired the idea for the design?

JR: I went to Yale as an undergraduate and saw Gordon Bunshaft’s design for the Beinecke Rare Book & Manuscript Library. I think it’s one of the greatest buildings ever built, and it is made of an amber marble that also has ferrous oxide in it.

ED: Now that the building has been unveiled, what do you hope people will take away from the design?

JR: This is a building for the performing arts and that begets a lot of mystery. The building must conform to pretty much anything artists can conceive of, and there is a radical flexibility to the interior. By cloaking the building in marble, we created a kind of “mystery box.” You can’t orient yourself to the outside and that’s intentional. It helps to create a suspension of disbelief. I totally fell in love with the marble material. You simply don’t know what it’s going to give you, and you must be prepared to move and change with it. I found that really poetic.

You Might Also Like