Is The Gilded Age's Opera War Based on a True Story?

"Hearst Magazines and Yahoo may earn commission or revenue on some items through these links."

“I’ve always been interested in the whole business of exclusion,” Julian Fellowes says. “I wrote in Snobs that if you leave three Englishmen in a room, they will invent a rule that prevents a fourth from joining them. I think all societies are based on exclusion; who isn’t good enough?”

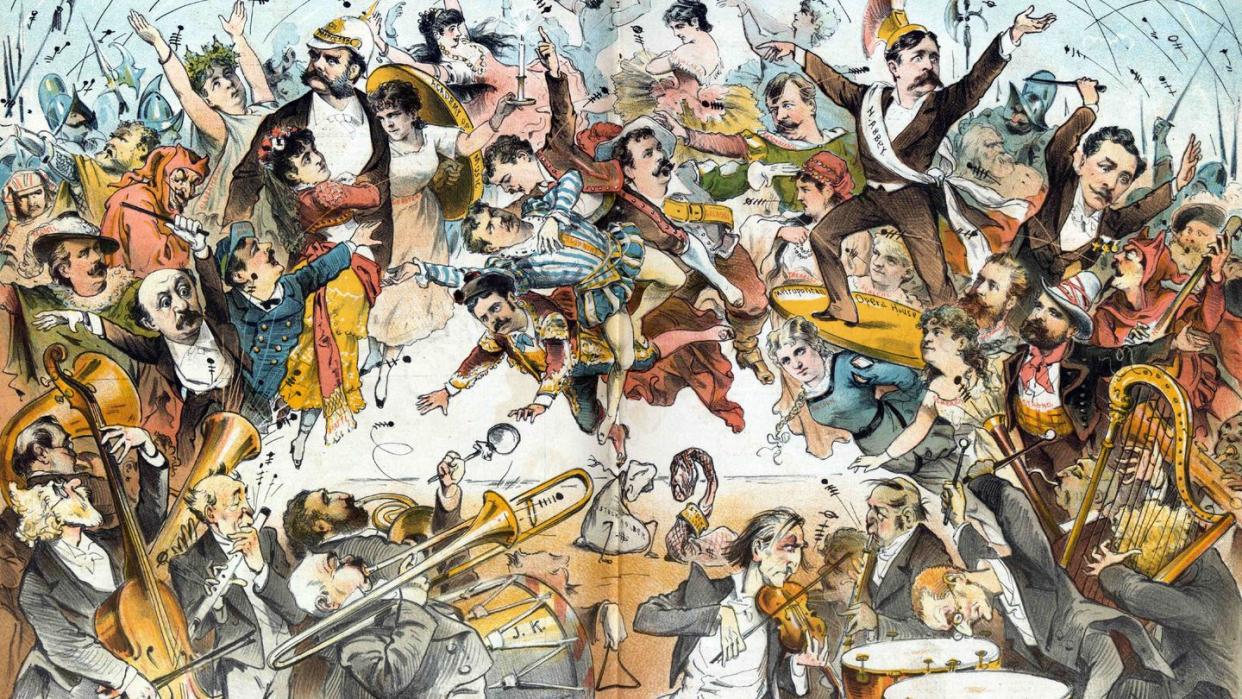

That interest has found an excellent outlet in the second season of the Fellowes-created series The Gilded Age, airing now on HBO. While there are slights at nearly every turn for his cast of characters, there’s perhaps no exclusion more important to the series’ new installments than the very true story of that at the Academy of Music, the now-defunct New York City opera house where the possession of a box was a sure sign of having arrived for the era’s most aspirational society types.

As fans of the first season will remember, the Academy’s most visible patron was Caroline Astor (played by Donna Murphy), and when she made it clear that the arriviste Bertha Russell (Carrie Coon) wouldn’t be finding herself in a box there anytime soon, Russell decided to throw her support behind the then-fledgling Metropolitan Opera. The new season follows what happens when the two companies careen toward their opening nights (to be held, of course, on the same evening), the loyalties of Knickerbocker money new and old are tested, and over-the-top drama and deceit make their way off stage and into the lives of these devoted patrons of the arts.

“I have a general rule,” Fellowes tells T&C. “I like to make historical references. Sometimes the characters just talk about something happening, and my secret dream is that people in the audience type it into Wikipedia and discover it really did happen. Sometimes we come upon real things and realize it’s an opportunity for our characters.”

That was the case with the opera wars, which really did take place in 1883. “I came upon the story because I was amused the Academy made the mistake of not just building 30 more boxes, which is what they should have done, but instead they thought they could keep the new people out,” Fellowes says. “What sealed it for me was when I read that they decided to open on the same night, so the fight between the two opera houses was a direct one and New York society had to choose who to support. If they had opened in different nights, people could have gone to both and seen how the different opera houses fared, but that wasn’t how it happened. A lot of them to cover themselves got boxes in both opera houses and then had to decide on the day which they were going to go to.”

As writer Sonja Warfield explains, “It’s about power. At the end of the first season, Bertha has her first big win with her debutante ball, but that’s not enough for her—she has to have more. The opera is like a country club: you have to have the membership, but it has to be the right club, and people have to see you there. The opera is the place to see and be seen for people who are power hungry and never satisfied.”

But how much did the story have to be changed to fit into the world of The Gilded Age? The answer is complicated. It’s true that both houses had their openings on the same night that year, and that the parties that supported them were each gunning to outdo the other but consider that some of Fellowes’s characters are real (like Astor and Marion Fish) and others are fictional, the plotline is certainly inspired by real events, but massages to make it work in an imaginary world.

“Part of Julian’s genius is balance,” says Michael Engler, a director of the series. “He’s always weaving in historical fact and mixing it with fiction in a way that feels believable. Take Mrs. Astor, we try to stick with what we know about her, but with Bertha Russell we don’t have to because she’s fictional.”

Producer David Crockett adds, “That’s my favorite part of working on this series. It’s almost like a cheat in some ways; we have this wealth of information knowing what really happened and we can cherry pick what works for our story. We can mine amazing, terrific, fascinating human stories and bring them to life for a few episodes or a whole season. That makes it fun for us and for the audience.”

Still, the real parts of the story are practically perfect for the cutthroat world that The Gilded Age portrays.

“It was well known that the Academy of Music on East 14th Street had a similar structure to the Met: a lot of stockholders owned the theater and rented it out to impresarios who put on opera seasons there,” explains Peter Clark, former director of archives at the Metropolitan Opera. “They only had 18 boxes at the Academy, and that was insufficient for the number of people who wanted to have box seats, which is what society did. As New York grew and there were more people in that class who wanted to be seen, the Academy didn’t have enough boxes. So, that group—which was centered around the Vanderbilts, Astors, and Morgans—decided to build a new opera house, and there was rivalry there.”

And the rivalry did cause the two factions to try to out do one another with swanky opening nights (which take place in this season’s finale of The Gilded Age), imported talent, and the promise of being seen a the right place on that fateful evening.

“At the Academy, there was a gentleman named Colonel Mapleson who put on a season based entirely around Adelina Patti, the most famous singer of her time,” Clark says. “The Met hired another theater producer, Henry Abbey, who put together a troupe in Europe headed by a Swedish singer named Christina Nilsson and put on its season. It’s true they were going head-to-head, and it was really a matter of who could last. There was an appetite for opera, but two big houses—and they were both big houses—trying to draw the same audience night after night was going to be impossible.”

Armchair historians might be able to find out easily which of the opera houses prevailed, but the fun of the opera wars as depicted on The Gilded Age isn’t so much the outcome of the rivalry as the wild antics that lead up to it.

“It’s such a wonderful image,” Fellowes says, “these women in diamond collars throwing themselves into carriages and shouting at their husbands to catch up, and the coachmen whipping the horses to get them into their boxes in time for curtain up. As I read that, I thought, oh yes, this is for me.”

You Might Also Like