Getting their names back: How three Austin-area residents help solve identity cold cases

Rhonda Kevorkian's first brush with genealogy came in 2009 when she became pregnant with twins and was curious whether there were others in her family tree.

She purchased a DNA testing kit in 2012, put some saliva into a tube and sent it to a lab. She found out about a half-aunt who lived two states away.

"My grandfather was a truck driver, and he drove his truck to that state. So it kind of all fell together," said Kevorkian, who lives in Pflugerville. "And then I actually met her, and now I have a new family member that I didn't know about before."

The experience inspired Kevorkian's professional transition, after two decades as a pediatric assistant, to an investigative genetic genealogist — first as a volunteer with Search Angels, helping adoptees find their biological families, and now as the executive director of human resources and education at the DNA Doe Project.

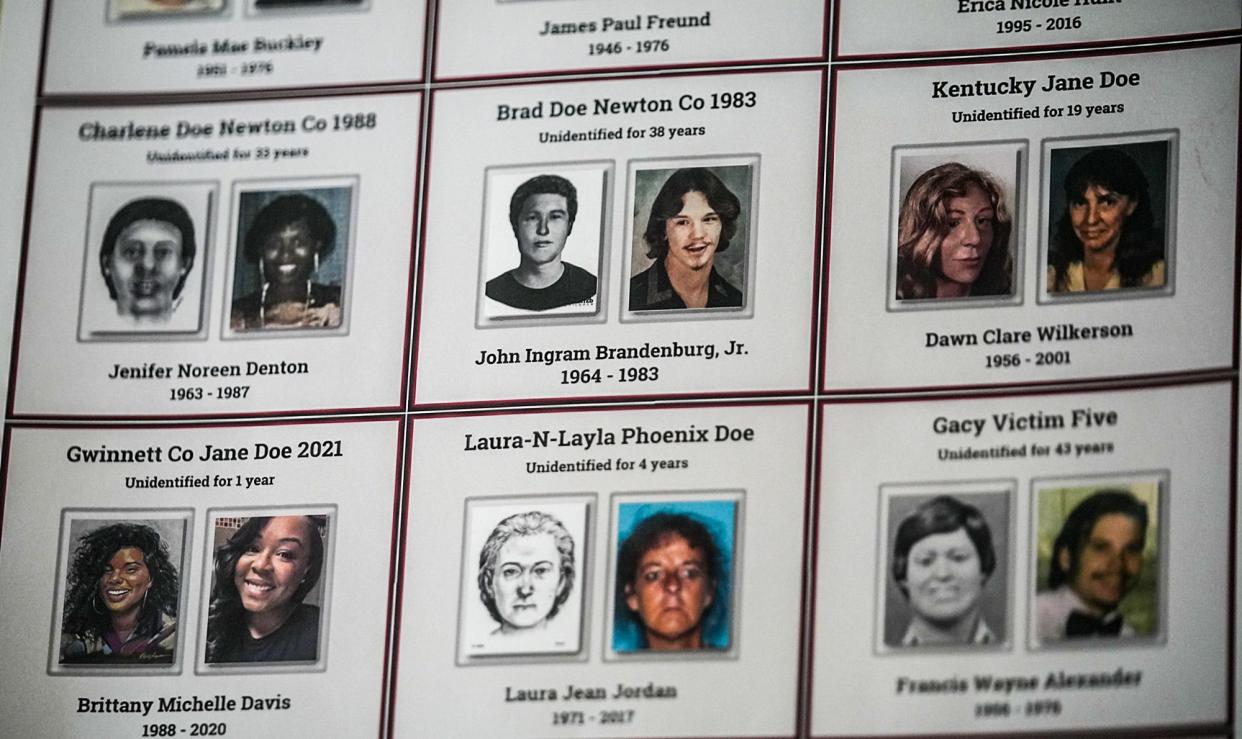

The nonprofit organization is reinforced by volunteers around the globe, helping law enforcement agencies advance cases by identifying deceased John and Jane Does across the United States and Canada. Since 2017, the nonprofit has helped verify the identities of more than 200 people, making a small but noticeable dent in the 50,000 sets of unidentified human remains in the U.S.

Kevorkian is hopeful that the organization can greatly reduce that number.

One of DNA Doe's recent successes was solving a nearly 40-year-old cold case in East Texas' Smith County this month. In 1985, a woman's body was found in a brush-covered gully on the side of Interstate 20, and authorities believed her remains were purposely concealed. She was identified as Sindy Gina Crow, who had last resided in Arlington.

"Everyone deserves to have their name back and a proper burial," Kevorkian said. "Family and loved ones deserve to know what happened so they can heal. To be able to be a part of that resolution is very profound. It's life changing."

Giving 'Does' their identity back

While each case is different, most, if not all, "Does" experienced homelessness; others were runaways or victims of homicide.

The organization doesn't turn cases away due to a law enforcement agency's inability to pay. Instead, it raises the money needed to perform costly genetic testing through donations and institutional grants.

However, sometimes science fails, and it's not always genetic genealogy that provides an identification, Kevorkian said. The role of social media and the general public is a salient part of investigations, having helped identify at least one Jane Doe in the past.

She said she spent two years on a particularly difficult case that wasn't getting anywhere. Then a woman heard about DNA Doe and uploaded her genetic material to GEDmatch, trying to find answers about her missing aunt.

"It was amazing to have been looking for so long, then the right person tested," Kevorkian said. "We had a name in a few short hours after seeing her match, and now Jane Doe is identified."

When cases grow too cold for law enforcement

Law enforcement agencies will contact DNA Doe and ask it to take on a case if it has reached a dead end. There is no minimum amount of time the case has to be cold for DNA Doe to be brought on to assist, Kevorkian said. The oldest case on its roster is from a 1944 Connecticut circus fire, in which some victims were burned beyond recognition. The organization is analyzing the remains of two victims, but the deterioration of their DNA has made the case particularly challenging. It is still pending.

After a law enforcement agency requests assistance, the organization determines the Doe's best-quality DNA sample. It is sequenced at a lab and uploaded to GEDmatch or Family Tree DNA, which distills profiles from consumer favorites such as 23andme and Ancestry.com. GEDmatch received its moment in the spotlight when it helped solve the notorious Golden State Killer case.

Austinite Kevin Lord left his career in tech to pursue private investigating, and that led him to DNA Doe in 2018. His current role includes shepherding samples through the lab process and helping the organization determine which DNA samples are optimal for testing. Samples can come from head to toe: He said enamel on teeth tends to protect DNA better; dense bones such as those in a foot or hand are also a good bet.

One lab specializes in extracting DNA from hair, even if it doesn’t have a root. A common challenge is the natural bacterial contamination, Lord said. Soil or water bacteria can often be an issue if a body has been buried or found in a waterway. He said DNA Doe has relied on trial and error, adapting techniques from other disciplines and pioneering most of its forensic analysis methods.

"Just in the last six years, we have made huge progress. Some of the samples we had trouble with in 2018 or 2019 are a piece of cake now," he said.

Lord foresees artificial intelligence helping the industry make more gains in coming years.

The extracted DNA helps reconstruct the Doe's family tree. DNA Doe's many volunteers help sift through family trees to identify anyone who might have gone missing or is otherwise unaccounted for, Kevorkian said.

She said she considers local cases especially dear. She is the team lead on two Travis County cases: Slaughter Creek Jane Doe, whose body was found in a wooded area behind an apartment complex on April 12, 2020, and Redbud Trail John Doe, a homeless man whose hanging body was discovered on May 27, 1998, by a water treatment plant employee. Funding is still pending in the case of another man who was declared dead within the Austin city limits on March 10, 2021.

Another team lead and Austinite, Lance Daly, has said that all his cases stay with him long after they've been solved. One Doe's family had failed to notice his disappearance.

"The jubilation at having solved a decades-long cold case quickly takes a backseat to the knowledge that someone is about to receive a death notification," Daly said. "They thought he was out in the world somewhere living life to the fullest. That’s what gets to me the most — those families who think they have the right answers, only to learn decades later that the narrative in their head was tragically mistaken."

The project's success stories are bittersweet, Kevorkian said, but they drive her to help more families.

"We do this for the families, who deserve answers," she said. "It may not be the answer they are looking for, but it's an answer, and hopefully they can begin to heal knowing what has happened to their loved one."

This article originally appeared on Austin American-Statesman: Team of Austin-area residents helps police solve identity cold cases