‘You’re getting crumbs.’ Kentucky to cut jobless benefits in 2023 as recession feared

Economists say the United States could enter a recession in 2023 under the drag of soaring prices and rising interest rates. Unemployment could rise over the next 12 to 18 months as the economy contracts, shedding 1.5 million jobs or more.

If so, the timing would be poor for Kentuckians who are thrown out of work. Starting Jan. 1, Kentucky will make its jobless benefits among the nation’s least generous for new claimants.

Last winter, under pressure from business groups clamoring for more job applicants, the Republican-led legislature passed House Bill 4 to spur laid-off workers back into the labor pool faster. Democratic Gov. Andy Beshear vetoed it, calling it “a cruel bill,” but lawmakers overrode his veto.

The new law cuts the maximum duration for unemployment insurance payments, down from the traditional 26 weeks, by “indexing” it, or tying it to the statewide unemployment average during a recent three-month span.

Also, it adds rules requiring people to apply for work more often than before and to accept a “suitable” job more quickly if it’s available within 30 miles of their home, even if the pay is much lower than their last job and it doesn’t match their skills or experience.

This is not welcome news in rural parts of the state where good jobs usually seem scarcer than they do in the metro “Golden Triangle” of Louisville, Lexington and Northern Kentucky.

In Eastern Kentucky counties like Magoffin and Martin, for example, the unemployment rate this year tended to be twice the statewide average.

Telling a laid-off worker to “get a job” is easier said than done when nothing with a decent wage is available in the area, said Owsley County Judge-Executive Cale Turner.

“We’ve got this attitude from too many damn people, in my opinion, where they worry about poor people getting crumbs. And when you’re living on unemployment, you’re getting crumbs,” Turner said.

In Owsley County, the unemployment and poverty rates remain stubbornly high. Although hundreds of at-home Teleworks USA jobs were created in recent years for people who are comfortable working on phones and computers, there still aren’t enough job openings in the county overall, Turner said.

“They’re making out in the legislature that these people are too lazy to work,” the judge-executive said.

“Well, that’s not true,” he said. “People here — people all over the world, for that matter — would rather work for a livable wage if they can find it than take unemployment. But how in the world do we expect people to live on jobs that pay $7.25 an hour, which is what some of these jobs pay?”

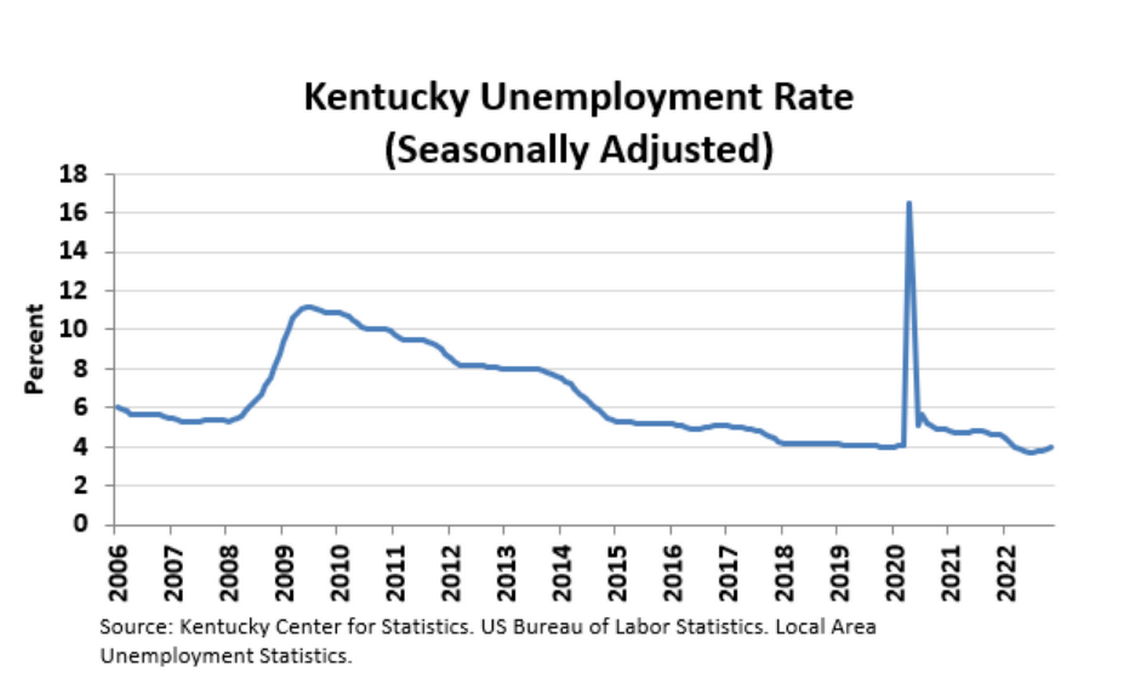

Under the new law, for the first half of 2023, Kentuckians will be eligible for only 12 weeks of jobless benefits — and pressure will be applied to start cutting them off after six weeks — because the statewide unemployment average was under 4.5% from July to September of this year. (In fact, it was 3.76%, although in some counties, it was twice that high. By November, the statewide unemployment rate had risen to 4 percent.)

If average statewide unemployment rises, more weeks gradually are added, but to no more than 24 weeks — two fewer than the current maximum. And three-month samples are taken just twice a year, meaning today’s benefits in every community are based on the health of the statewide economy six months ago.

The new 12-week cutoff will bring a shock to the system in the first six months of 2023. On average this year, in a period of relatively low unemployment, Kentuckians collected jobless benefits for 17 weeks, with an average weekly benefit of $382, according to state data.

The 26-week safety net for laid-off workers has been a national standard since the Great Depression in the 1930s. But a handful of states, prodded by business groups that want to reduce the unemployment insurance taxes they pay that fund jobless benefits, recently began to experiment with indexing.

There never was a good time for Kentucky to reduce jobless benefits, said Dustin Pugel, policy director at the Kentucky Center for Economic Policy in Berea. Still, making the change ahead of a likely recession is particularly cruel, Pugel said.

“I think a lot more people are going to run out of benefits a lot sooner than they would have otherwise,” said Pugel, who has studied the new law.

“Nobody has a crystal ball. We don’t know what’s going to happen economically next year,” Pugel said.

“But the point of unemployment insurance was to be there when there is widespread job loss — when a plant closes down — or even when an individual worker goes through a layoff. You want there to be enough flexibility that workers can find another position that matches their career field, their skills, their pay,” he said.

The law’s primary sponsor, state Rep. Russell Webber, R-Shepherdsville, declined to be interviewed.

In a prepared statement, Webber said: “HB 4 takes into consideration potential economic crisis as well as the challenges hardworking Kentuckians may face.”

“However, it also emphasizes the importance of returning to the workforce and provides for additional job training and requirements,” the statement read. “House leadership has pledged to work with the Labor Cabinet if additional funding or guidance is necessary to implement changes, but we’ve heard nothing from the administration to date. Of course, we also have the opportunity to make any necessary changes when we convene in 2023.”

Ken Troske, a labor economist at the University of Kentucky, said it’s too early for him to judge the wisdom of states reducing and indexing their jobless benefits.

It should be noted that in the 1930s, when the 26-week benefits limit was created, job seekers had to read newspaper want ads and walk the streets to find employment, and now they can search more efficiently on computers and phones, Troske said.

On the other hand, Troske said, Kentucky risks pressuring workers — especially high-skill workers who are uniquely qualified for certain positions — into rushing to accept available jobs that don’t fit their abilities. That could squander people’s skills, make them unhappy and create inefficiencies in the economy, he said.

“Unemployment insurance was set up so people could have a period of searching for a job that’s a good match for them and what they want to do,” Troske said. “That’s a valid argument. We think there is a combination between the skills of the worker and what an employer is looking for. There is no question that that’s important.”