In a game of inches, Phillies come up just short as Astros even World Series

HOUSTON — At the end of the regular season, we tally wins and losses, of course. Home runs and strikeouts, barrels and rotations-per-minute. We measure the non-counting stats relative to the rest of the league and adjust for ballpark and era. The point is quantification and comparison — to better understand in retrospect whether what we were watching was good or bad.

These calculations are important for remembering as much as for record-keeping (and what is the latter, really, if not a communal repository for triggering the former?). All sports do this, but baseball especially worships the large sample sizes above all else. What you see in real time is considered less relevant than the cumulative history.

How much that applies to the postseason has become a theme of this particular October — can you call the team you watched win “better” if the bigger picture tells you otherwise? But even when the World Series doesn’t feature an 87-win team that marauded through the earlier rounds, upsetting division winners and self-serious guardians of the sport’s sanctity, the narrow focus is part of the appeal of the playoffs. With entire fan bases living and dying on every pitch — not to mention the careers at stake — minutia becomes emotional, memorable, meaningful. At least in the moment.

The top of the eighth inning was arguably the most entertaining frame on Saturday night in Houston, even though it wound up factoring not at all into the Astros’ 5-2 win over the Phillies in Game 2 of the World Series. The bottom of the first had two runs scored on four pitches, the bottom of the fifth featured Alex Bregman’s 15th career postseason home run and in the top of the ninth the Phillies mounted a brief comeback threat. But for a little while in the scoreless eighth, things were really weird.

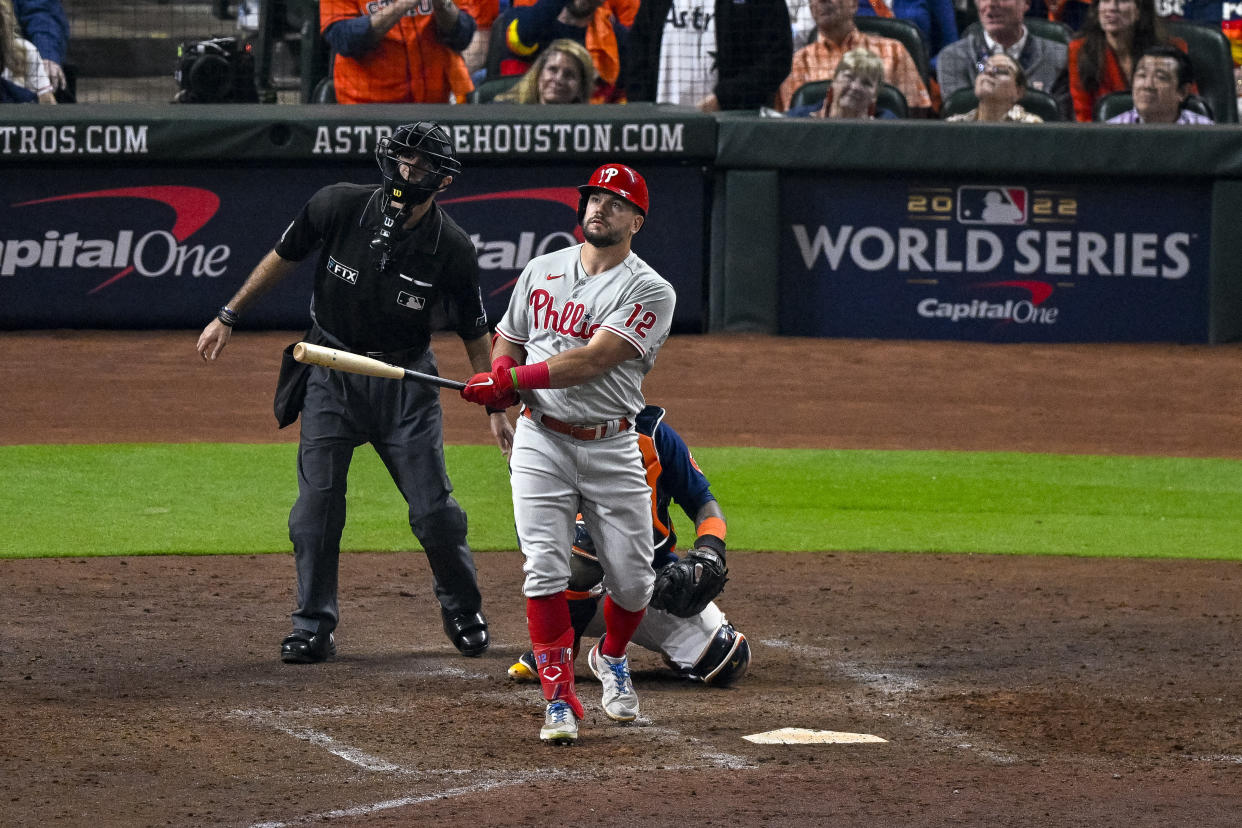

First, Bryson Stott walked, normal enough. That brought up Kyle Schwarber, notably exactly the kind of guy you would expect to hit a game-changing home run. And so when he took a mighty cut at a 2-2 fastball from reliever Rafael Montero, the broadcasters launched into the kind of call that crescendos when the ball clears the fences.

“It’s gone!” Joe Davis called as it disappeared into the seats just beyond the foul pole nonsensically imploring fans to “ROOT 4 THA CHIKIN,” Philly’s deficit down to two.

As Stott and Schwarber circled the bases and a broadcast graphic declared the home run had traveled 403 feet off the bat, the umpires assembled to undo what had been done. The 403 feet part was right, but the home run was not. Upon closer inspection, the ball was foul. The bombastic blast didn’t even change the count. After several minutes of not-quite baseball, the at-bat resumed as if nothing had happened.

"It was close, but it was foul," Schwarber said postgame, no point in keeping up the act at that point

On the very next pitch, Schwarber smashed the ball 353 feet to a clearly fair part of right field, on the do-over he would do it again. Back, back, back Kyle Tucker went till he was up against the wall, where the ball landed harmlessly in his glove.

Seven-hundred and fifty-six feet and only an out to show for it — put it in the scorebook: F-9.

After Rhys Hoskins struck out, J.T. Realmuto smacked a bouncing grounder up the middle that was scooped by shortstop Jeremy Peña and shoveled … right over the head of José Altuve, crouched facing the other direction. Altuve — whose three-hit night offered ample redemption — expected Peña to throw to first, Peña thought the only out was at second, the result was a gaffe that created a visual glitch in the game.

Errors are always sliding doors, and sometimes impactful ones at that. They underscore how we take for granted the talent required to keep any game on the rails. The routine outcomes are themselves the result of something incredible, namely the often machine-like ability of professional athletes to execute flawlessly.

This one wasn’t especially extreme or inexplicable, but it was evocative. Plus it looked really silly. Less like stumbling over the curb and more like walking into a glass door. No one scored on the play — with Stott advancing to third — but the ball sailing over an oblivious Altuve as part of a pass to no one must’ve sent Astros fans’ stomachs sinking as momentary confusion reigned.

A few pitches later, Bryce Harper flied out and the inning was over, no damage done. A zero on the scoreboard just like any old scoreless inning.

The easy takeaway is that baseball remains a heartbreaking game of inches and instants. So often the losing team walks away feeling like they were one swing away, or else something even smaller — a half step, a gust of wind, a bad bounce, a couple of feet this way or that.

But the non-moments matter, too, and not just for the what-ifs they contain. It’s all part of the fabric of watching a game, rather than just knowing what happened. There’s nothing we love more in sports than the superlative or standalone, to be able to point to a contextualized number that proves something happened that has never happened before, to know you’ve witnessed something different or new. But if you expand your purview beyond the eventual outcomes, I bet there’s some of that in every game; you just have to look closely enough.

Eventually, perhaps they too will be reduced to what can be reflected in the box score and what is worth replaying in highlight reels. But for now, these World Series games are self-contained dramas as much as they are a means to determining a victor. It’s ironic, really, because the winner matters so much, we take time to pay attention to everything else, too.