As fungal infections grow resistant to medication, desperate patients try drug after drug

After living with a severe fungal allergy for about 40 years, Jill Fairweather is running out of treatment options.

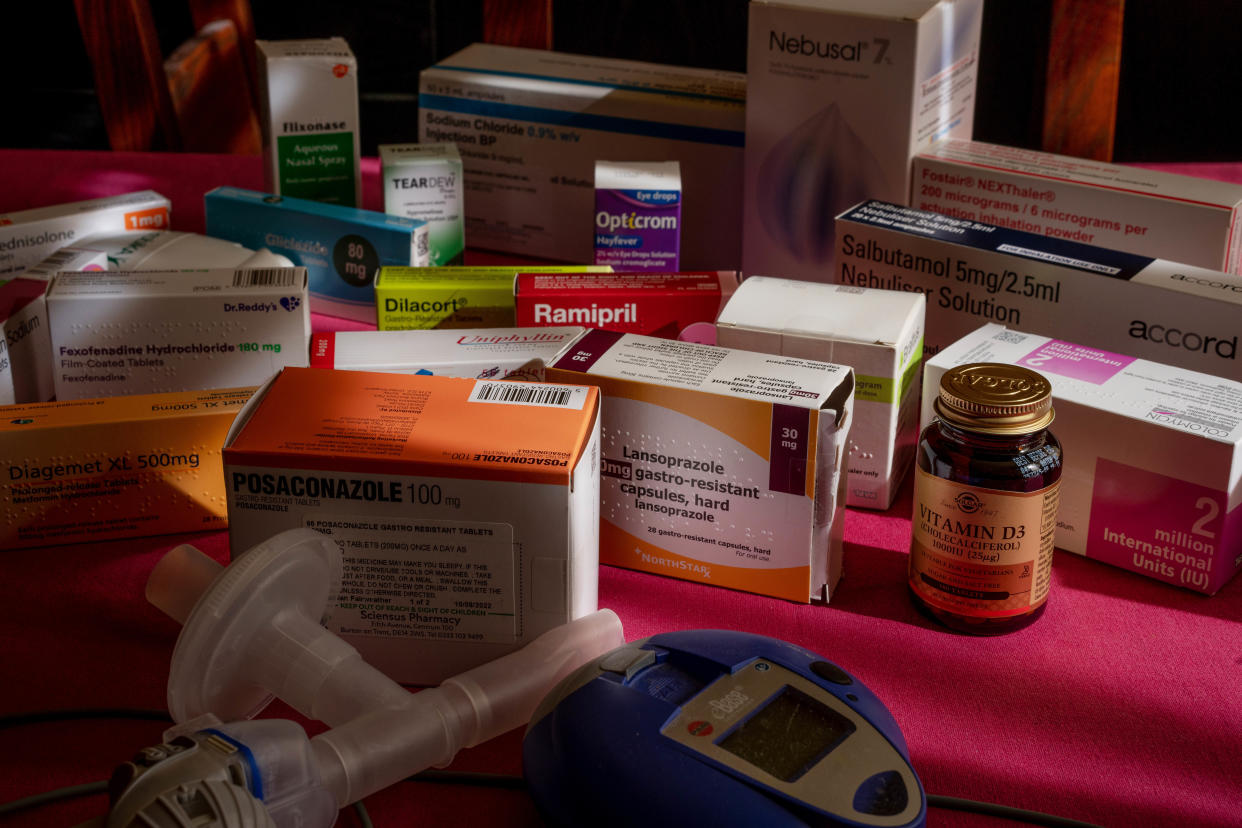

Now 65, Fairweather was diagnosed with aspergillosis, a disease caused by the common mold Aspergillus, in her 20s. The illness can result from an allergic reaction or an infection in the lungs. Over the years, Fairweather has tried medication after medication, switching once side effects get too dangerous or the fungus develops resistance.

Aspergillus and another fungus, Candida auris, are growing resistant to the treatments frequently used to fight them — in particular, a class of drugs called azoles.

"If we lose that drug class because of resistance, we’re in for big trouble," said Darius Armstrong-James, an infectious disease physician at Royal Brompton Hospital in the U.K.

Fairweather has a rattle in her chest that she said feels as if she’s trying to expel a piece of rubber. Sometimes she coughs up blood.

After she developed resistance to an inhaled antifungal medication often considered a last resort, Fairweather started on an intravenous drug cocktail that recently required a two-week stay in the hospital on an IV drip.

"If the intravenous treatment stops working, I’ve run out of options," she said.

Globally, around 4.8 million people have lung disease from allergy-based aspergillosis like Fairweather's, according to a 2013 estimate. The survival rate of chronic lung disease from aspergillosis was 62% at five years and 47% at 10 years, a 2017 study found.

Doctors anticipate more cases like Fairweather's as fungal infections become more prevalent in Europe and the U.S.

Candida auris infections rose more than eightfold in the U.S. between 2017 and 2021, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention — from 171 annual cases to 1,420. In the U.S., the mortality rate of an invasive Candida auris infection ranges from 30% to 60%.

That fungus usually affects people in health care settings. In May, Nevada's state health department recorded Candida auris outbreaks at 19 hospitals and nursing facilities.

The CDC does not track aspergillosis in the same way, so it's hard to know how prevalent cases are. But hospitalizations related to invasive aspergillosis — severe infections in people with weakened immune systems — rose 3% annually from 2000 to 2013, according to one study. A CDC report published Wednesday showed that the U.S. recorded more than 14,000 hospitalizations for invasive aspergillosis each year.

The report highlighted the case of a 65-year-old man who underwent a stem cell transplant. Afterward, doctors prescribed him azoles to ward off a fungal infection, but they detected Aspergillus in his lungs more than three weeks into his hospital stay. A second type of azole also failed to stop his infection, and he died less than a week later.

The report determined that the patient had been infected with an Aspergillus species that’s resistant to azoles — one of the same strains Fairweather has.

Patients with invasive aspergillosis from this drug-resistant strain have a mortality rate of around 60%, according to the CDC.

How fungi invade the body

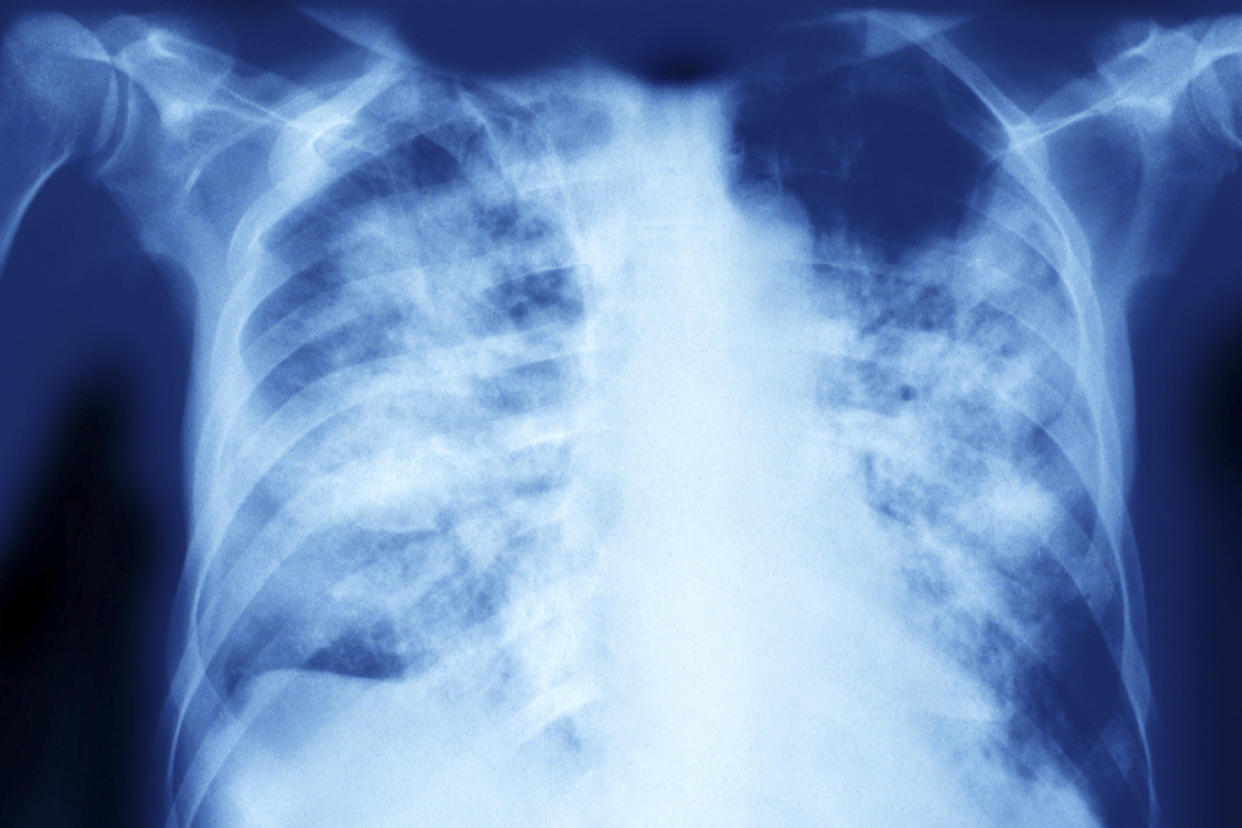

Most healthy people inhale Aspergillus frequently with no consequences. The spores lingers in damp homes, soil, seeds and decaying vegetation.

"You live on Earth and breathe, you’re going to get Aspergillus in your lungs," said Dr. Peter Pappas, a professor of medicine at the University of Alabama at Birmingham.

But in people with weakened immune systems or chronic lung conditions, the fungus is a threat.

Fairweather, who lives in Berkshire, England, had severe asthma as a child, which likely made her more susceptible to aspergillosis. Still, she took corticosteroids and lived fairly normally until her 40s, when she started to get ill frequently.

If she caught a cold, Fairweather said, “I would end up being off work for two weeks and have a chest infection or end up with pneumonia.”

Franklin Dobbs, a 76-year-old patient of Pappas’, also had pre-existing lung problems before he was diagnosed with aspergillosis last year. Dobbs said he hemorrhaged on and off for about a year before getting diagnosed. His case has thus far not proved drug-resistant.

An azole called Noxafil improved his symptoms, Dobbs said, though he still feels weak.

“I’m still having a problem with the strength in my legs,” he said.

Dobbs believes he might have been exposed while planting tomatoes, corn and peas in the garden, or while building birdhouses outdoors.

An April study found that people can get infected with drug-resistant Aspergillus from their home gardens. The researchers collected lung samples from infected patients in the U.K. and Ireland, and matched some of them to drug-resistant strains in the environments nearby.

Sometimes, a single high-dose exposure, such as a cloud of spores released by digging in soil, can be enough to trigger a fungal infection. But in many cases, people are gradually exposed to Aspergillus over months before they become ill.

“This is an extremely concerning superbug-type situation,” Armstrong-James said. “We’re all inhaling this all the time. So potentially, we could all be inhaling resistant Aspergillus on a daily basis.”

Unlike Aspergillus, Candida auris is mostly detected in hospitals, among people who are on breathing or feeding tubes or receiving a central line (an IV catheter that administers fluids, blood or medication).

"When you have one of those medical interventions that are in patients, you become at risk of it getting into your bloodstream or creating an abscess, and that’s when it’s very dangerous," said Luis Ostrosky, chief of infectious diseases at UTHealth Houston and Memorial Hermann Hospital.

More than 90% of Candida auris strains are resistant to the common azole fluconazole, and up to 73% are resistant to another called voriconazole. Some strains also have resistance to the drug Fairweather recently stopped taking.

"You can end up with a patient with a Candida auris infection where you actually don’t have an antifungal to use for that patient. It’s resistant to everything," Ostrosky said. "Basically those patients go to hospice and die, and there’s nothing you can do."

Why mold is growing resistant to drugs

Researchers have pinpointed two main drivers of antifungal resistance: human drugs and chemicals used in agriculture.

Farmers often rely on fungicides, but over time, certain strains of mold become resistant. And since fungicides are chemically similar to antifungal drugs, some mold strains develop resistance to the medications too.

The 65-year-old man who died of invasive aspergillosis, for instance, was infected with a strain linked to agricultural fungicide use, according to the CDC.

"Bulbs and onions that have been dipped in these antifungals so they don’t spoil are almost like time bombs. When they’re planted, the fungicides that are on their surface will leak out into the environment," said Armstrong-James, who co-authored the April study on Aspergillus.

"That could be a key breeding ground for resistance," he added.

Drug use contributes to resistance when antifungal drugs are prescribed too often, or if doctors don't prescribe a high enough dosage or long enough treatment course. That can then put selective pressure on fungi.

“The more you use antifungals or antibacterials, the more resistance that you see,” Pappas said.

Armstrong-James said that hospitals see resistance to Candida auris more frequently than to Aspergillus.

"Every time anyone takes fluconazole, you can get Candida resistance," he said.

Climate change and Covid may each play a role

Climate change may be catalyzing the spread of both Aspergillus and Candida auris.

That's because rising temperatures can lead to more fungicide resistance. Some research suggests that climate change was a key driver of Candida auris’ first appearance in people in 2009.

"Within a very short period of time, you’ve got the emergence of four or five different families of Candida auris more or less co-emerging simultaneously. How does that happen? It really screams if there’s something going on in the environment," Pappas said. "There’s decent evidence that climate change is at least one of the triggers."

Some experts worry that as climate change's effects intensify, even some healthy people could get fungal infections.

"Whilst there’s no evidence for the moment that a perfectly well person could get a severe Aspergillus infection, there’s nothing to say that, with the changing environments, that might not change in the future," Armstrong-James said.

On top of all this came the Covid pandemic, which created new opportunities for Candida auris to spread. A July CDC report found that these infections rose 60% in health care settings from 2019 to 2020.

"Invasive Candida infections just skyrocketed with Covid, presumably because all these patients were sick," Pappas said. "They were given broad spectrum antibiotics. They had lines and ventilators and all the things that you need to generate invasive Candida."

The CDC report found that staffing shortages and lengthy patient stays, among other factors, made it difficult for some hospitals to prevent drug-resistant infections.

"We were having all these traveling nurses that came from different parts of the country that weren’t necessarily attuned to the protocols that the hospital normally has to prevent bloodstream infections," Ostrosky said.

New treatment options could take years

Doctors say they're in a race against time, since current treatments could stop working before new ones become available.

“If we don’t manage resistance right now and if we don’t boost the pipeline for the antifungals, we may very easily end up in a place in five to 10 years where you’re having end-of-life discussions with a patient that has an invasive Candida infection," Ostrosky said. "It's just unthinkable right now that your loved one can go into the hospital and have an appendectomy, and they get a complication, and they end up with a bug that’s untreatable."

Several drugs have entered late-stage studies that could produce results in the next year or two, experts said.

But Fairweather isn’t sure she’ll get a chance to try them.

"How much damage will be done to my lungs before these things come into effect?" she said.

Plus, fungi could develop resistance to new medications over time.

"Once they’re out there, they get overused and then pretty quickly, they’re no longer useful," Pappas said.