Former Miami resident wanted to save strays in Venezuela. Now he’s the one in need of rescue

On the night his life was ruined, animal-rights activist and former South Florida resident Jonatan Palacios, 39, got a call no one ever wants to receive: The SUV carrying his family through a mountainous road in western Venezuela had plunged off a cliff.

The vehicle, which served as an animal rescue ambulance for the non-governmental organization he founded, had fallen more than 200 yards, flipping several times as it plummeted against the ravine wall, violently hurling off most of its six occupants before finally landing upside down.

Witnesses of the Jan. 14, 2021, crash told the Miami Herald that the driver came out of a curve to find two big tanker trucks traveling fast downhill towards him through both lanes of the narrow two-lane road. Fearing his vehicle was about to be squashed, driver Jesus Caicedo, 34, attempted to maneuver out of the way, but ended up turning into the abyss.

Three people died in the crash, including Palacios’ 4-year-old adopted daughter, Giselle. Her mother and Palacios’ romantic partner, Anyelly Parada, 23, survived but sustained severe injuries, as did the other two survivors: Yirenny Villalba, 22, and Abigail Guerrero, 29. The activist, who reached the site hours later that night, was actually the first to reach Giselle’s body after climbing down and searching the area in the dark. The police and rescue officials at the scene refused to do it even though the survivors were screaming, asking for help, from down below.

Stricken with a profound rage and grief, Palacios demanded an investigation in the following days, talking first to authorities and later repeatedly through social media, saying that the tankers not only caused the accident, but that they were not even supposed to be there, given that there was a strict prohibition for cargo vehicles to travel through that road at night.

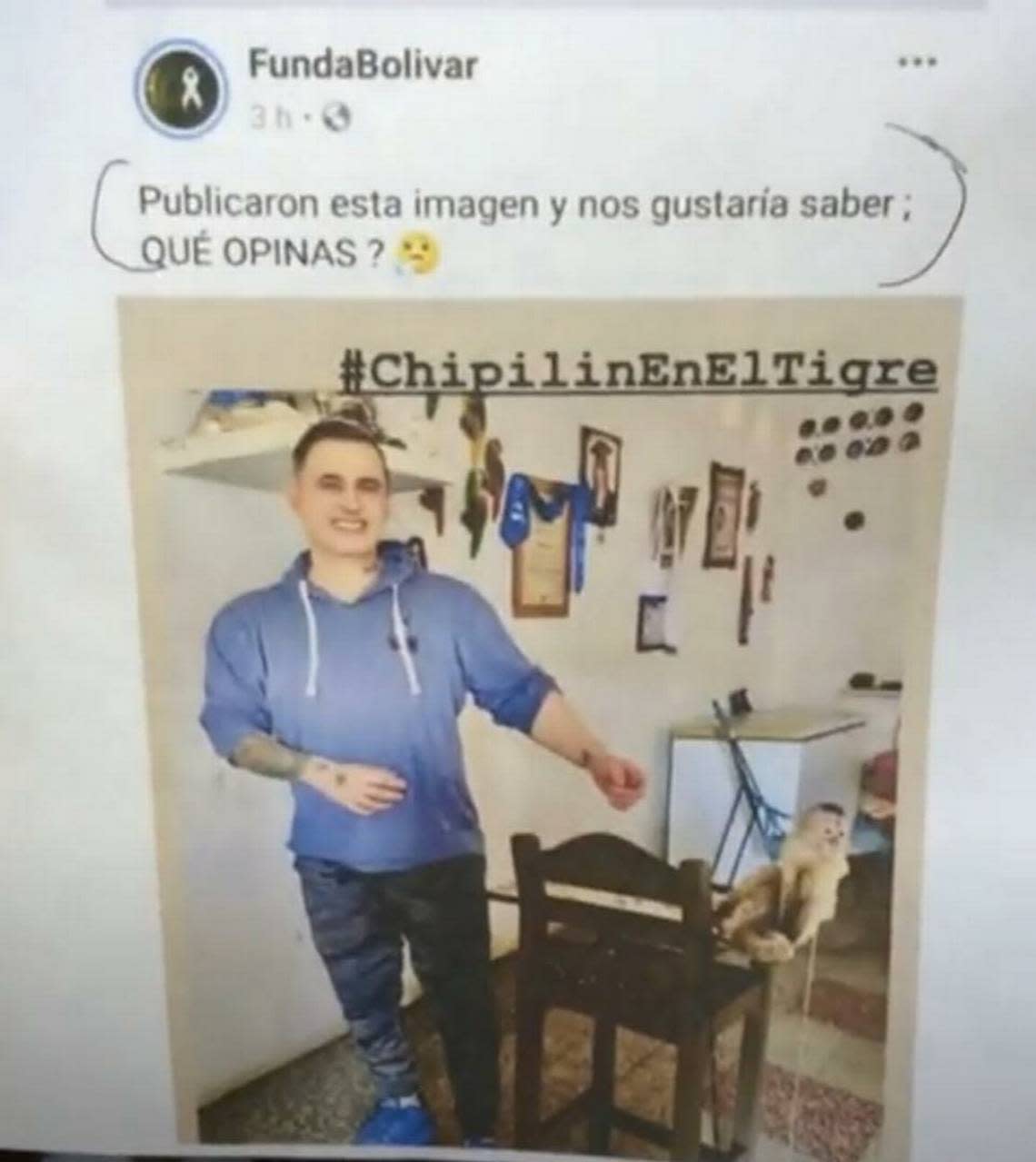

But instead of justice, Palacios’ public denunciations landed him in jail. The reason? The trucks, which belonged to the state-run oil company PDVSA, were carrying fuel for a smuggling ring headed by a high-ranking government official. The final straw was when Palacios tweeted a photo of the country’s attorney general posing next to a monkey, while protesting his lack of action in the case.

The activist, a former South Florida contractor who graduated from North Miami Beach High School, has now been in prison for over two years and is currently held at Centro Penitenciario Occidente CPO2 Santa Ana, in Tachira state, under what he calls hellish conditions. His life is in perpetual danger, he says, given that all Venezuelan prisons are under the control of gangs and inmates die every day.

And yet, he is innocent, says lawyer Raquel Sanchez, who forms part of the Venezuelan human rights nonprofit organization Foro Penal, which watches over and often attempts to provide legal defenses for political prisoners in the South American country.

“There is no real legal basis for his detention,” Sanchez said. “His imprisonment is the result of an act of retaliation after he denounced the lack of investigation of a tragedy where his 4-year-old stepdaughter died, along with two workers of his organization.”

Other people familiar with Palacios’ case told the Miami Herald that the activist was imprisoned for publicly revealing the regime officials behind the fuel smuggling operation.

Palacios, who was born in Colombia, is among hundreds of victims of Venezuelan officials’ blatant use of the judicial system to persecute dissidents or simply those who dare to stand in their way. Wielding total control over the nation’s judges, regime officials are often the ones deciding individual rulings.

“The independence of the judiciary has become deeply eroded,” a United Nations report said in 2021. “Under intensifying political pressure, judges and prosecutors have, through their acts and omissions, played a significant role in serious violations and crimes against real and perceived opponents committed by various State actors in Venezuela.”

The report concluded that the use of Venezuelan courts to jail and torture dissidents is systemic, but Palacios is not political. HIs organization, Funda Bolivar, was dedicated solely to the rescue of stray pets in the bordering Tachira state, often providing a home and medical care for them.

“The work that they were doing is beautiful,” said Nelson Salas, an Orlando resident who regularly donated money to the organization. “Jonatan and his team demonstrated a profound love for Venezuela and for all types of animals.”

According to Salas, Funda Bolivar would rescue and provide veterinary care for animals that had been run over or abused — in some instances, some were hacked with machetes by people attempting to kill them — and provide them with a safe place to live while searching for a new home. They also held vaccination and adoption campaigns and tried to educate residents on the importance of caring for animals.

Depending solely on donations, the organization grew to become the largest of its kind in Venezuela, and by 2021 employed 35 people who cared for the hundreds of animals brought in to their headquarters in San Antonio, Tachira.

At times their efforts to save animals included an element of danger, Salas said. “If they found a place holding either dog fights or cockfights, Jonatan would go there and try to stop them, making sure all of those present were aware they were participating in an illegal activity. He did this at great risk because these are betting events and the organizers normally are not little angels.”

On a dark winding road

Funda Bolivar would also report to authorities when they detected animal abuses.

Palacios was in the process of filing such a complaint on the night of the accident but decided to send his family and other coworkers ahead to their homes in the nearby town of Rubio, because it was already 9:30 p.m., while he waited for the electric company to reestablish their interrupted service in order to meet with police officials.

About an hour and a half later, he got the call. “I was in complete shock, I couldn’t believe what I was hearing,” he told the Miami Herald. Desperate, he grabbed the radio to communicate with members of his animal rescue network, asking for help, and headed toward the area in a motorcycle, stopping to pick up one of his workers on the way.

When he arrived at the scene, he found that the traffic police and agents of the National Guard were already there, but no one was doing anything for the victims. Just then, Palacios heard “a horrible scream” from Parada, who was calling out from the darkness for her daughter.

“I started to yell and tried to jump off the cliff to reach where the vehicle had fallen but the National Guard did not let me,” Palacios said. “I was desperate, I yelled to the National Guardsmen, why don’t we do something? Let’s grab each other by the hands to form a human chain and climb down. But they were not willing.”

Yirenny Villalba, a veterinarian who after surviving and recovering from injuries suffered in the accident was forced to leave Venezuela, said that all but one of the six occupants were thrown from the vehicle and were lying, severely wounded, at different points at the bottom of the cliff but could not see each other in the dark.

Giselle had apparently died almost immediately, but Caicedo, the driver and the organization’s wildlife director, had initially survived and the others heard him crying out before he died, Villalba said. Guillermo Ayala, 62, a gardener who had been hired to maintain the headquarters’ landscaping, also survived initially and cried out for help several times, but died before anyone could reach him. Those who survived suffered multiple fractures that eventually required surgery.

“We spent more than six hours laying there waiting for help. The accident took place around 10:30 p.m. and the first of us they reached was taken out around 4 a.m.,” Villalba said.

Palacios said that he was the one who actually found Giselle. Frustrated by the lack of action from the National Guardsmen, he went to another area on the side of the mountain where people told him he could reach the ambulance. He, with the help of others, searched in the dark among the bushes and jagged rocks and found the little girl after a while.

“She was lying facedown, bleeding from her mouth. I picked her up and she let out a sigh. I thought then she was alive. I picked her up and hugged her, but then felt her body totally destroyed. I moved her away to see her better and realized that her eyes were lifeless,” he said.

Threats and nonexistent trucks

Palacios was infuriated the following days not only for the initial lack of action by the authorities, but by the fact that from the beginning they moved to cover up that the PDVSA trucks had caused the accident. That night he saw a captain of the National Guard cornering a witness and telling him that he should never mention the tankers were there if he wanted to avoid problems. Officials kept pressuring the witness, who afterward decided to leave the country.

The same happened at the clinic where the survivors were being treated. Police investigators told the women they had been either drunk or on drugs because the tankers did not exist.

Palacios decided to go public, which ended up sealing his fate, Salas said. “In Venezuela, one must tread carefully and first know who you are dealing with,” he said. “Jonatan was blinded by the situation and went out to denounce not only those who were responsible, but those who are really behind the fuel smuggling operation.”

Palacios publicly blamed the current governor of Tachira, Freddy Bernal, a former Venezuelan police official who was sanctioned by Washington for providing weapons to Colombian leftists guerrillas and who has strong ties with the armed paramilitary bands closely allied with the regime known in Venezuela as Colectivos.

Government officials controlling the border have for years been involved in fuel smuggling, taking advantage of the low prices for the subsidized product in Venezuela to sell it for huge profits in Colombia. Press reports published in 2021 revealed the participation of Bernal and his Colectivos in Tachira state in a criminal racket that earns them millions of dollars each month.

In a letter sent recently to Colombian President Gustavo Petro asking for help, Palacios said that he was invited in February 2021 by Venezuela’s investigative police, CICPC, to their offices to discuss the events that led to his daughter’s death. Once he entered a room inside their offices, he said, he was beaten without being told why and shoved into a jail cell.

“From that day forward, all my rights have been violated,” Palacios said in the letter to Petro. “I was tortured and my personal integrity has been violated since the CICPC officials not only beat me and used the other prisoners to cause me physical and psychological damage, but my honor was publicly destroyed after Attorney General Tarek Saab published on his social media that I was a Colombian criminal.”

Saab said on Twitter that Palacios was an international swindler and prosecutors charged him with 17 different crimes. For lack of evidence all but one of them were tossed aside. The only one that remained was inciting public hatred when he tweeted a photo of Saab next to the monkey. More recently, he was charged with smuggling after using a cellphone inside the prison to post a video of a blind inmate commenting about his life behind bars.

Cellphones, however, are readily available in Venezuelan prisons for anyone willing to pay for them.

Besides Palacios, officials arrested other members of Funda Bolivar, the organization’s president Yilmar Campo and Parada and tried to intimidate them into falsely testifying against the activist. They were imprisoned for months.

Zair Mundaray, a former Venezuelan prosecutor who is now exiled in Colombia, said he has looked into the Palacios case and believes that even though the activist became a target after he exposed the fuel smuggling operation, it was the photo he posted about Saab that prompted the charges against him.

But the case against Palacios is preposterous, Mundaray said.

“Saab appears as a victim in the case but at the same time he is the prosecutor because he is in charge of the whole prosecutorial system in Venezuela. In the end, he is a prisoner of Saab in a case that legally has no merits,” Mundaray said.