Forensic genealogy breathing new life into unsolved Columbus police homicide cases

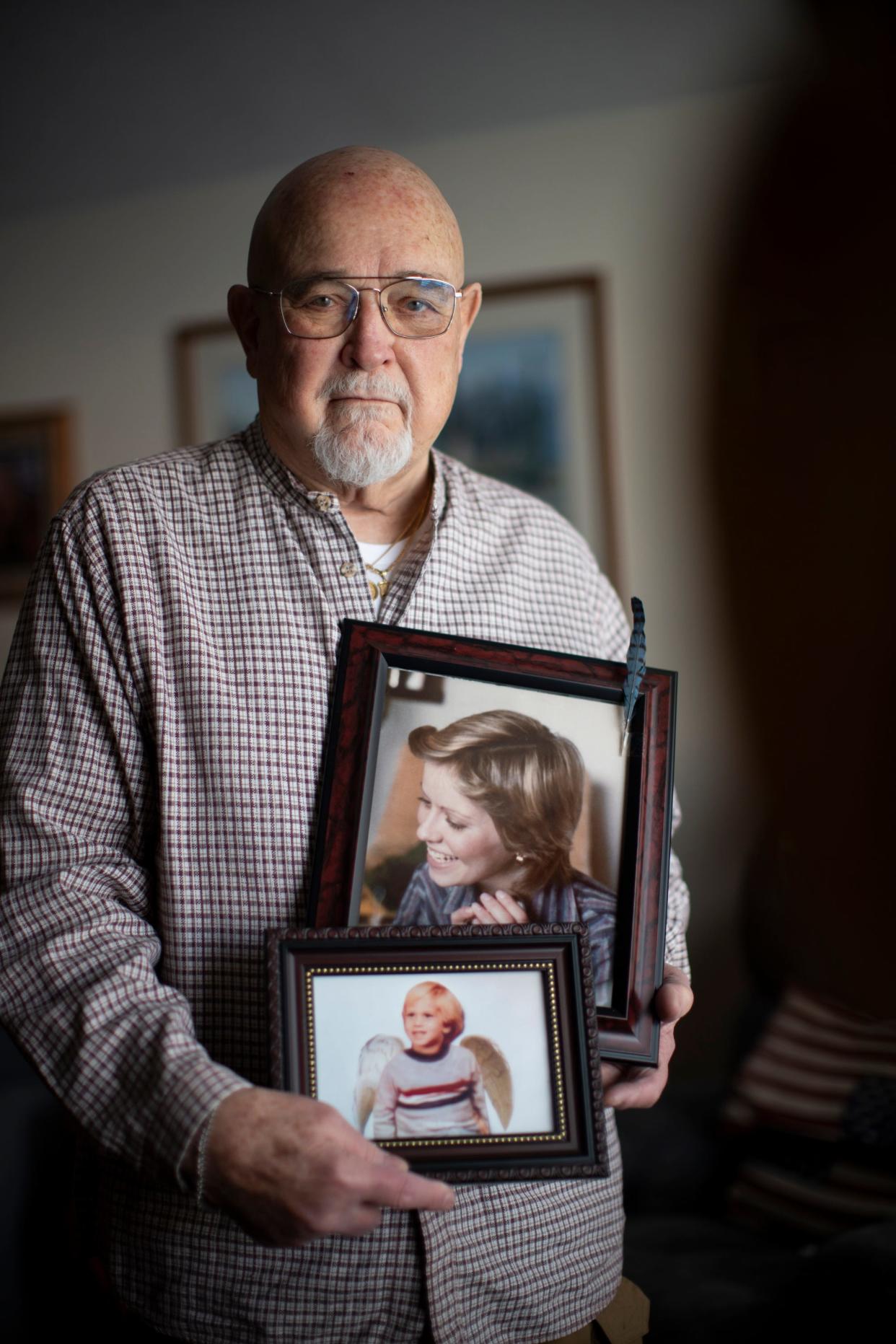

More than 43 years have passed since someone killed his daughter and grandson, and Don Hochuli often thinks about the type of person his grandson, Jeremy Pickens, would have become.

"He'd be 46 years old," the 88-year-old Hochuli said. "You wonder what he'd have been like. How many more great grandkids would I have?"

Jeremy was 2 ½ years old on Nov. 12, 1980, when he was found suffocated in his aunt's car along with 23-year-old Lynn Hochuli Vest, who was strangled to death. The case remains unsolved after more than four decades, one of more than 1,000 unsolved homicides in Columbus police's archives.

Columbus detectives have renewed hope that technology could hold the key to helping people like Hochuli find peace by uncovering who committed some of the city's most violent unsolved crimes.

What is genetic genealogy?

Columbus homicide detectives have identified dozens of cold cases where genetic genealogy might provide renewed hope. The technology has gained popularity in particular because of its use in high-profile cases like the Golden State Killer in California.

A 2023 report from the Institution of Engineering and Technology estimated that more than 400 cases worldwide have been solved because of genetic genealogy.

Among those was the 1982 abduction and murder of 8-year-old Kelly Ann Prosser who disappeared while walking home from school. In 2020, Amanda Reno, a genetic genealogist for Advance DNA, and Sgt. Terry McConnell, who oversees the detectives tasked with reviewing unsolved Columbus homicide cases, announced they used genetic genealogy to identify Kelly's killer.

DNA from the crime scene matched through family DNA to Harold Jarrell, who died in 1996.

Reno and McConnell stayed in touch, consulting on other cases before formalizing the arrangement, and Reno began working part-time for Columbus police in late 2023. She maintains her position at Advance DNA, a private company. She is believed to be the only investigative genetic genealogist working with a police department in Ohio and one of only a handful nationwide.

"It's really becoming the next big thing like CODIS was to DNA and AFIS was to fingerprints," McConnell said. "We didn't want to be bringing up the rear."

Genetic genealogy uses publicly sourced DNA results from websites like GEDMatch.com to provide leads in cases where DNA evidence is available.

More: Columbus unsolved murders of 2 college students to be topic of NPR-owned podcast

Investigators like Reno trace back the DNA from a scene and possible suspect to the point of a match with DNA from a genealogy website then begin tracing family trees for possible relatives. Any potential match is confirmed with DNA testing of a close relative or the actual suspect if they are still alive.

The practice is not without controversy. Popular DNA testing websites Ancestry.com and 23andMe have both been involved in lawsuits about the use of DNA from their online databases being used by law enforcement.

How does forensic genealogy work?

Reno said the process of investigative genetic genealogy, sometimes called forensic genealogy, begins by reviewing the original case file to determine what DNA evidence may exist and whether the case will meet the criteria needed to be eligible for genealogical testing.

The criteria include whether a case was a violent crime, if DNA for a potential suspect already exists in CODIS, the DNA database used by law enforcement, and if the investigation has reached a point where all other leads are exhausted.

Investigators will reexamine the evidence to determine how much DNA remains and only pick a case if there is enough DNA to gather additional samples if needed at a later date or if additional testing is needed. Then, Reno works to identify the specialized laboratory to which the sample will be sent for testing.

Crime labs for Columbus police and the Ohio Bureau of Criminal Investigation don't have the capability to perform the type of genealogical testing required by the process, so Reno identifies an outside lab where the sample goes for additional testing.

Then, the waiting begins.

"It's like Christmas, and the presents are under the tree, and you're sitting there wondering what's in them. That's where we're at with all these cases right now," McConnell said.

The lab testing and DNA extraction process can take weeks or months because of the growing demand for the services and the limited number of facilities to do the testing.

The process of waiting can sometimes end in disappointment, Reno said. If a submitted piece of evidence has too much of a mixture of DNA from multiple people, it may not be able to be used for genetic genealogy.

"Realistically, the technology hasn't gotten to the point today where it can be worked with, and you may not know until you get far enough in the lab process," she said.

However, if a result can be provided to police, Reno said that's when her work really begins.

"We have a list of DNA relatives that will pop up, but they can be any sort of relationship," Reno said. "I have to take that list and sort that into some type of logic."

More: Photos | Cold case: 1970 slayings of Mary Petry, William Sproat

Knowing who killed twin still won't solve 1970 mystery

Finding out who killed 20-year-old Mary Petry and her 22-year-old boyfriend William Sproat at a home near Ohio State University's campus in 1970 would only bring small satisfaction to Mary's twin sister, Martha.

"I really would like to know why," Martha Petry said. "That's much more important than any punishment."

On Feb. 28, 1970, Mary Petry and Sproat were found murdered in a home on West 8th Avenue. Both had been stabbed multiple times and had skull fractures and other broken bones.

Martha Petry said she still has letters that her twin wrote her, every line crammed with information about Sproat, from what restaurant they had eaten at to how the pair enjoyed speaking in French to each other.

Petry said she and Sproat's sister both believe the person who killed their siblings may have known them because of how violent the crime was. The attempt to use new technology to try and find answers about what happened is a blessing for Petry.

"This is not about justice, it's more about mercy," she said. "The mercy is knowing the mystery. It has always been there, but it wasn't something that I could dig into because it had such an emotional weight to it, but during COVID, after I had retired, there was a new sense of asking why."

Should the evidence at the scene yield a potential genealogical match, Petry said she knows it may not give her the answers she's looking for about why her sister had to die.

"My universe is not one that's about an eye for an eye," Petry said. "There may be a reason. There may be understanding of something that I don't understand."

Age not a factor in whether forensic genealogy will work

The age of a case doesn't necessarily preclude the possibility of there being DNA evidence that could be used in forensic genealogy, Reno said. Some of the evidence collected by detectives who had no idea what DNA was, like in Mary Petry and William Sproat's case, may still hold clues.

"Some of the stuff we have ... it might not have been paid attention to at the time because DNA wasn't a big thought, but we have it," McConnell said.

There are also more recent cases that may benefit from genetic genealogy. All new Columbus police detectives undergo training on the technology and what type of evidence has to be collected.

"Why sit around and wait 20 years for it to get cold and be unsolved if we can solve it with something like this," McConnell said.

Detectives are also continuing to review older cases that might be good candidates for forensic genealogy, McConnell said, but families may not always be told the review is being done.

"There's somewhere you have to reach out to them and let them know what we're doing, but it's just not fair to give false hope," he said.

"There's situations that may be setting a family up for a big disappointment," Reno said.

But other families, like Hochuli's, are strong enough to know the process is underway because of all they've endured in the decades since their loved ones were killed, McConnell said.

"They can get the DNA from places they were never able to get it from before," Hochuli said. "I'm always hoping for something to come up."

Hochuli said he doesn't believe whoever killed his daughter, who was so cautious she locked her car in her own driveway, and his grandson is still living.

"Anybody, any criminal that does something like that, somebody has killed them," he said. "People who would do that and live that lifestyle, it catches up with them."

Even if the person or people responsible are dead, Hochuli still wants to know who they were so he knows where to direct his anger and frustration. He said a friend who had also lost a child to violence once told Hochuli that if God could forgive the killer, he could forgive a parent for not forgiving the killer.

"Forgiving him, that's a no," Hochuli said. "Some people say they forgive the person. Them, maybe, but not me."

Anyone with information on an unsolved homicide is asked to call Columbus police detectives at 614-645-4036 or submit a tip through Central Ohio Crime Stoppers at 614-461-TIPS. More information about unsolved Columbus homicides can be found online.

This article originally appeared on The Columbus Dispatch: Columbus cold cases: How genealogy testing may help solve homicides