Foreclosure spree in Black neighborhoods benefited investors, didn’t end code violations

When the city of St. Petersburg began to aggressively foreclose on property owners with outstanding code violations eight years ago, the idea was for the city to get these properties into the hands of new owners who would take better care of them and improve the surrounding neighborhoods.

But the vast majority of properties that were sold to new owners through the city’s foreclosure spree have since been cited for new code violations even after changing hands, a Miami Herald data analysis found.

In many cases, the purchasers were companies not individuals, and they were able to resell the properties for substantial markups.

Roughly two-thirds of all the properties that changed hands as a result of the foreclosure drive accrued at least one violation under new ownership, the Herald found. Some of the properties have incurred dozens, including some bought by companies with roots in Miami.

What’s more, at least half a dozen companies that bought foreclosed properties were themselves the targets of earlier foreclosure lawsuits brought by St. Petersburg over unpaid code fines. That includes some of the most prolific purchasers of foreclosed properties through the program, who have incurred numerous violations since taking ownership.

Not included in the totals are 12 properties that the city itself purchased that had potential infractions that didn’t result in violations formally being issued. While the city’s code department occasionally issued violations to municipally owned properties, citizen complaints about such properties were far less likely to result in formal action than privately owned properties that were the target of similar complaints, the Herald’s analysis found.

A Herald investigation earlier this year revealed that the program in St. Petersburg targeted the city’s majority-Black neighborhoods resulting in the loss of homes that had been in families for generations. These are often referred to as “heirs property.” The private lawyer hired by the city to file the foreclosure lawsuits, Matt Weidner, later signed contracts with numerous other Florida counties and cities to pursue similar efforts.

The investigation found that after inking deals with Weidner, several municipalities turbocharged the number of foreclosure lawsuits they filed. St. Petersburg filed more than 425 after hiring Weidner in 2015 — a vast increase over the number it filed before hiring Weidner. By comparison, the city of Miami, with a population that is 1.7 times greater, has filed fewer than 50 such lawsuits in the same period.

Families lose homes after Florida cities turbocharge code enforcement foreclosures

These increased foreclosures in St. Petersburg and other Florida cities are particularly significant because of stark racial differences in wealth passed down from one generation to the next. The share of Black families that inherit wealth is half the share of white families that do so, according to research by the Federal Reserve. And the average inheritance received by white families is nearly three times the average received by Black families.

A combination of socioeconomic factors and historical discrimination make Black families more vulnerable to the loss of so-called “heirs property,” which has often been passed down between generations without all the required legal paperwork.

When the foreclosure program first began in St. Petersburg, Weidner told the Tampa Bay Times the focus would be on derelict properties owned by real estate speculators hiding behind networks of shell companies.

“They don’t have the reputational risks that encourage them to be good citizens,” Weidner said at the time.

But the effect has been the opposite.

More than half of the suits by the city were filed against individual owners and less than a third were filed against businesses, according to court records analyzed by the Herald.

By contrast, around two-thirds of the roughly 250 foreclosed properties re-sold by the city were snapped up by real estate companies.

St. Petersburg and Weidner, the attorney, did not respond to numerous requests for comment.

Frank Schnidman, a retired professor of urban and regional planning at Florida Atlantic University, said it’s no surprise that investors would be attracted to the program but that the outcomes show St. Petersburg failed to establish proper guidelines for buyers.

“It was the rulebook that needed to be changed,” he said.

‘The rich get richer’

Among the biggest buyers — and code violators — are a series of companies tied to the Babcock Investment Company, once a prominent South Florida development firm.

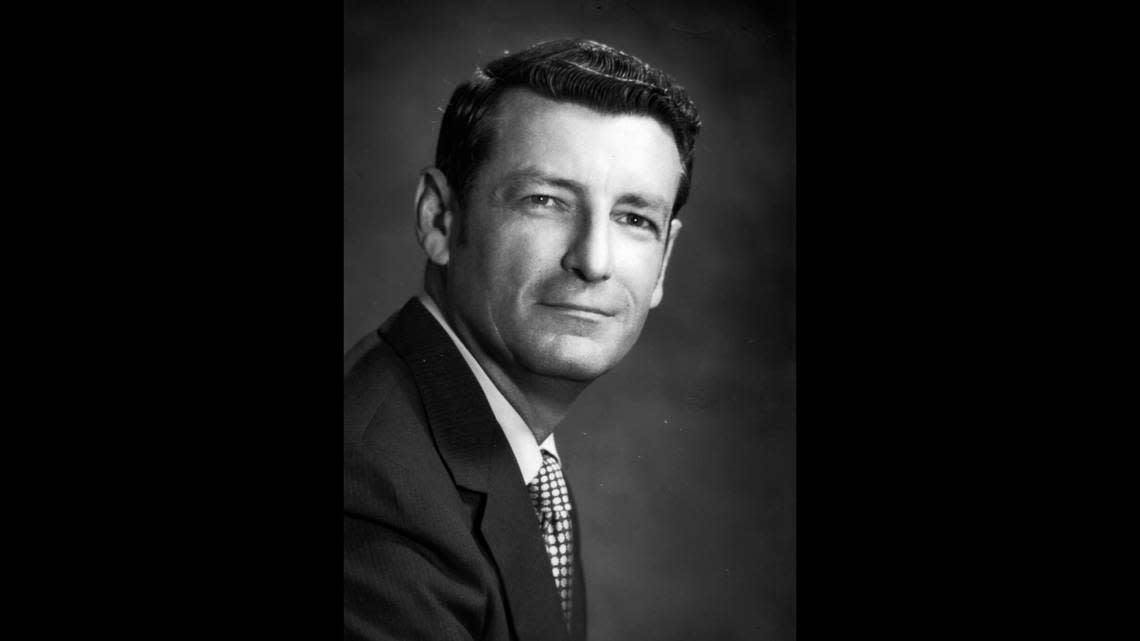

The business was founded by Charles Babcock in Miami right before World War II, the Miami Herald reported in 1984. By the 1970s, the firm had built and developed thousands of homes and commercial projects in South Florida and Charles Babcock’s son, Charles Babcock Jr., became, per the Herald, a prominent figure in the city, serving on the board of governors of The Greater Miami Chamber of Commerce and chairing the Miami chapter of the Salvation Army. In the aftermath of the 1980 riots, Babcock Jr. helped redevelop Liberty City. He was awarded a Spirit of Excellence award by the Herald in 1987.

Babcock Jr.’s son moved his family and the business to Clearwater in the 1980s and capitalized on the real estate market in the Tampa Bay area. A fourth-generation Babcock, Chris, then joined the business and created a South Carolina arm of the firm in 2015. Today the company operates in both South Carolina and the Tampa Bay area.

A network of trusts and shell companies with ties to the Babcocks acquired roughly 20 properties that were targeted in St. Petersburg’s foreclosure drive.

The three main firms behind the buying spree are Reditus Capital, LTCF and Trustee Asset Services. Corporate filings and property records show the involvement of Chris Babcock, Thomas McCormick and James Kasper in all three the companies — though the exact relationship is not clear. Kasper describes himself as a vice president of the Babcock Investment Company on his LinkedIn profile as well as the owner of his own firm, Kasper Modern. McCormick, meanwhile, appears as an officer on numerous corporate filings with Babcock.

The properties purchased by this network of companies have been among the most prolific code violators of any properties sold through the program, the Herald’s analysis found.

The properties bought by the Babcock-affiliated firms racked up more than 100 violations combined. One property in the Harris Park neighborhood was cited for more than a dozen violations, including overgrown vegetation, trash and debris littering the plot and tree branches encroaching onto the sidewalk.

The network of companies continued to buy properties in the program even as one of the companies, Reditus Capital, was named in three lawsuits filed by St. Petersburg for outstanding code fines, with Babcock personally having been served notice in South Carolina in two of them.

While two of the lawsuits were dismissed, one of the properties was ultimately foreclosed upon and sold by the city in 2018, with the city saying it was owed nearly $34,000 in fines and fees.

The buyer?

Trustee Asset Services, which listed Babcock, McCormick and Kasper as three of its officers in corporate records filed earlier that year. The company bought the property for $9,200 at auction — a discount of more than $24,000 from the debt due to the city.

The Babcock-affiliated companies spent just under $540,000 on the properties they purchased and have sold nearly all of them for a combined total of more than $3.4 million. That represents nearly six times what they paid for the properties, though the companies did build new homes on some.

One of those properties was a vacant lot in the Child’s Park neighborhood of south St. Petersburg.

Darien Bell and Manuel Jones had plans to build on the lot and provide affordable housing for veterans in connection with their non-profit group Veterans & Community Resource Center. But the city sued to foreclose in November 2019 in connection with roughly $9,400 in unpaid fines over clearing the lot.

Bell and Jones both filed motions arguing that they hadn’t been properly notified of the suit, but Pinellas-Pasco Circuit Judge Thomas Minkoff signed off on the foreclosure and the sale went through.

The property wound up being bought in June 2020 for $16,900 by a trust associated with LTCF. Months later, the city issued two code violations on the property for overgrowth and trash and debris, but LTCF ultimately built a sleek, three-bedroom house on the lot, with quartz counter tops, custom cabinets and stainless steel appliances and sold it in late 2021 for just under $360,000.

“The rich get richer,” said Bell, a former professional football player who now works in real estate.

Babcock, Kasper and McCormick did not provide responses to the Herald’s request for comment.

Golden opportunity

Also benefiting from the program were companies tied to Clearwater investment guru Tom O’Brien, which bought at least 16 properties that had been targeted by St. Petersburg. All told, those properties were issued roughly 50 violations, according to city records, for violations including overgrowth, junk and inoperable cars parked on the properties.

All those purchases were made after two of the O’Brien companies — 525 Capital Management and Tiger Real Estate Opportunity Fund 1 — were the target of foreclosure lawsuits brought by the city over unpaid property fines. Both lawsuits were dismissed and O’Brien’s companies kept the property.

O’Brien, the host of a daily online radio show and digital broadcast aimed at investors, wrote a book about trading and is the author of two subscription newsletters. One, his weekly Gold Report, helped him make a name for himself as an expert on the commodity, with numerous television appearances on CNBC around a decade ago.

O’Brien hails from south Boston and said he saw parallels between where he grew up and south St. Petersburg, which he thought made it an attractive area in which to invest. The properties he purchased through the foreclosure program were just some of many properties he acquired in the area — including the ones St. Petersburg would sue him over.

“I felt St Petersburg was ready to take off,” O’Brien said. “The goal was to build on them for the next 20 years of my life.”

While O’Brien said he has built dozens of homes in Palmetto Park and other parts of south St. Petersburg, he hasn’t been able to build on all of the properties he bought. The properties he acquired through code enforcement foreclosures all remained vacant during his ownership of them.

They were, however, a good investment.

His companies paid less than $100,000 combined for the foreclosed properties and sold them for many multiples of that amount.

They packaged half of the properties, along with a number of other distressed properties they had purchased, in two separate sales in 2020 and 2021 worth a combined $1.8 million to companies associated with the Austin, Texas-based real estate investment firm Amherst Holdings.

They sold another five properties for nearly eight times what they paid for them. They still own two of the properties they purchased.

‘A lot of history that’s gone’

The city previously acknowledged to the Herald that many of the properties sold in the early stages of the program wound up in the hands of developers and said it took steps to mitigate that, including buying many of the properties itself.

The Herald’s analysis found that while few properties bought by the city were issued code violations, a number of them were the subject of citizen complaints, according to code records.

Of 16 citizen-initiated code complaints about properties owned by the city, only one resulted in a formal violation. That’s a stark contrast with the outcomes for citizen-initiated complaints against privately owned properties.

The Herald’s analysis found that a citizen-initiated code complaint against a privately owned property is more than 50 times more likely to be cited than a city-owned property.

Tony Atwater had been hoping to keep a vacant lot that had been in his family for generations. Located a half mile north of Lake Maggiore in south St. Petersburg, it was next door to his grandparents’ house. Atwater’s grandfather grew mangoes, watermelon and peas on the lot during Atwater’s childhood.

Atwater and his son were the last caretakers of the lot, mowing the grass and making sure the property taxes were paid. Atwater, who works in information technology, thought that the family might build on the property to provide a home for some of his elderly relatives. Atwater said he was told by the city that there were no outstanding issues with the property in 2017, but Weidner filed a lawsuit on behalf St. Petersburg to foreclose on the property in September 2018 over code violations Atwater hadn’t been aware of.

Atwater was told he’d have to pay more than $14,000 to keep the empty lot, which was more than what he thought it was worth. Atwater had hoped to get the property put in his name and try to work out a forgiveness plan with the city, but he ran out of time and four months after the suit was filed, a judge ruled to take away the property.

The city would ultimately build a three-bedroom house on the land, which it sold in 2022 for $335,000 as part of an affordable-housing program. During construction, a neighbor contacted the city’s code enforcement division, saying that the property was an eyesore, “littered with construction trash, concrete boards and siding.” The complaint didn’t result in a formal violation.

Several years later, the property is still a sore subject for Atwater.

“I still ride by the block and see the house,” he said. “That’s a lot of history that’s gone, no longer there.”

McClatchy Washington Bureau’s Amelia Winger contributed to this story.

Methodology

The Miami Herald identified around 430 lien-related foreclosure cases Matt Weidner has filed on behalf of the City of St. Petersburg and built a database recording relevant details about each lawsuit. The Herald then collected data on code-enforcement violations in the City of St. Petersburg for the properties that were foreclosed upon and sold off in auctions from the city’s code compliance online application.

The Herald also used state corporation records, lawsuits, deeds and press releases to map out the networks of the new owners of the properties. The Herald then classified the owners into “company” (limited liability companies, incorporations, limited partnerships and business groups), “individual” (named persons), “trust” (trusts and “TRE”), “city” (City of Saint Petersburg) and “other” (nonprofits and others).

Besides analyzing for violations and complaints by owner and owner-type, the Herald also performed regression analysis to compute the likelihood of a complaint being sustained by different ownership types. (The p-values for the regressions were well below 0.05 — rendering them statistically significant.)

Sources

Pinellas County Court, City of St. Petersburg, Florida Division of Corporations

Edited by

Casey Frank

Graphics by

Sohail Al-Jamea, Gabby McCall, Rachel Handley, Susan Merriam