Football, baseball, basketball ... chess? The legend of Kyler Murray

A few weeks after he led Allen High School to the second of his three straight Texas state football titles, Kyler Murray walked into a Chick-fil-A with some teammates to order lunch.

The employee behind the cash register blurted out, “You’re Kyler Murray!” Then he told the heralded high school quarterback, “Your food is on us!”

Behind Murray in line was Cole Carter, a starting receiver and senior captain on that state championship team. Carter approached the same cashier thinking he too would get a free meal, but what he left with was a bruised ego.

“I freaking had to pay for it!” Carter said with a laugh. “Captain on the state championship team, and I had to buy my own chicken sandwich.”

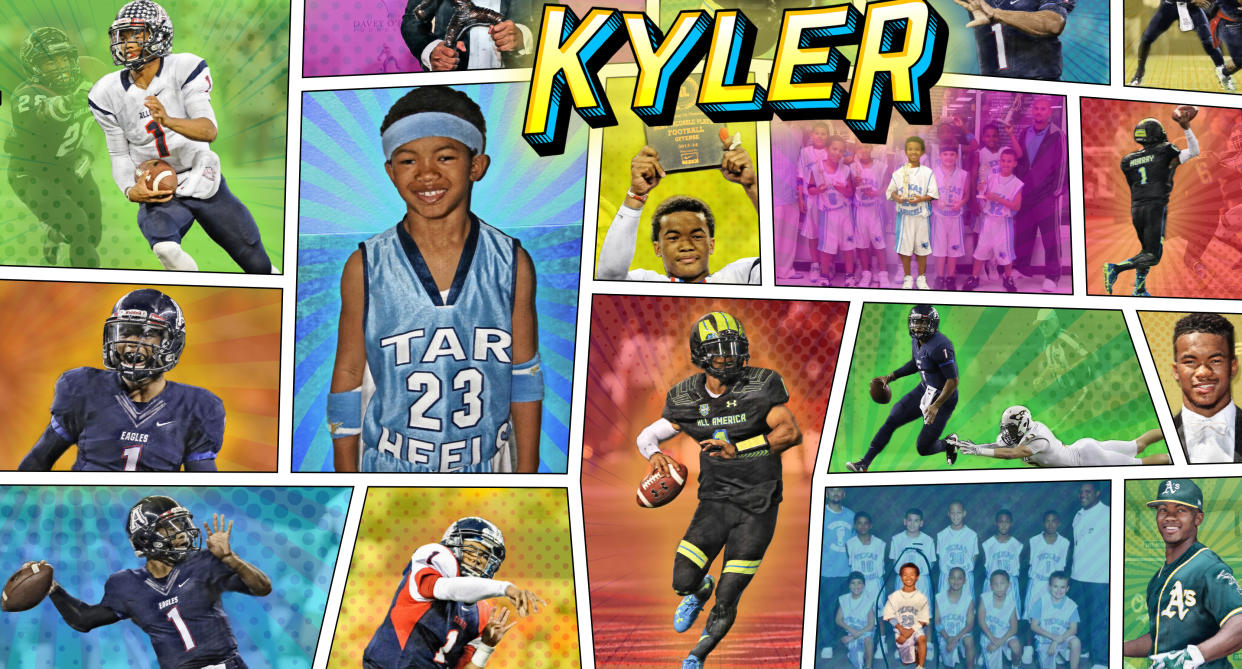

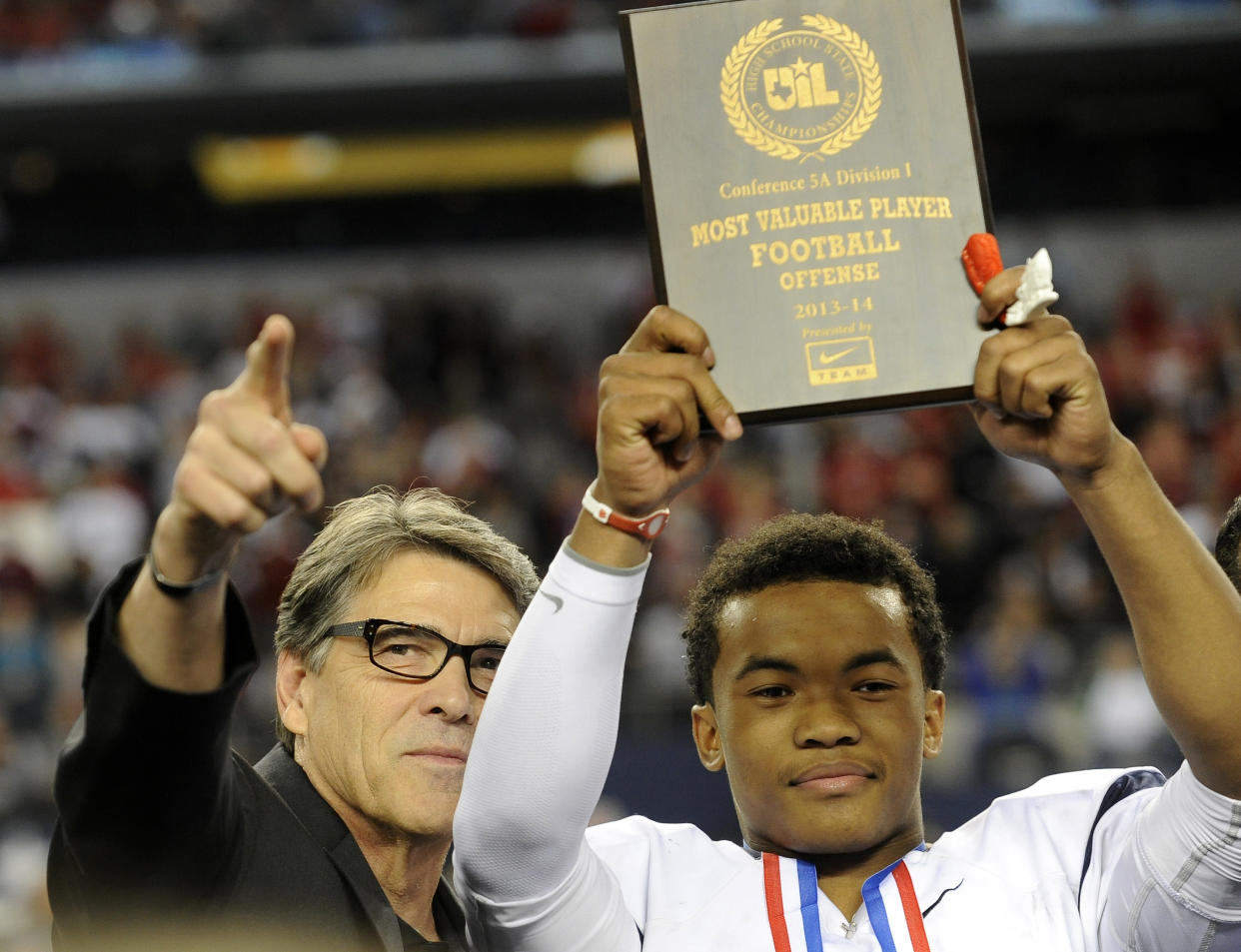

Whereas many NFL stars didn’t become household names until blowing up in college or blossoming as pros, the Murray mystique began to take root far earlier than that. Murray’s rocket arm and slippery feet became the stuff of legend in football-obsessed Texas long before he won the Heisman Trophy at Oklahoma, became the No. 1 pick in the 2019 draft and led the Arizona Cardinals into playoff contention this season.

There was the time that Murray ignored his middle school coach’s signal to punt and dashed 85 yards for a touchdown. Or his unprecedented 42-0 record in three seasons as a varsity starting quarterback. Or the RBI double he delivered with his jersey untucked and his shoelaces untied after showing up in the second inning of a playoff baseball game.

He even boasts a pair of elementary school chess championships in his trophy case.

Everyone who grew up with Murray, played with him or coached him has a favorite story. Here are some of the best:

When Kyler was 5

In the fall of 2002, the president of a suburban Dallas youth football league received a phone call that stoked his curiosity.

A friend urged Kyle Nelson to go see a quarterback who was piling up touchdowns in the 5-6 age group with astonishing ease.

When Nelson arrived at the football field and asked which kid was Kyler Murray, other spectators pointed to a 5-year-old who was smaller than many of his teammates. Nelson questioned whether he had the right kid until the game began and Murray lined up in a shotgun formation.

“The very first play, he swept to the outside, took off and left everybody by 20, 30 yards,” Nelson said. “I'll never forget that. I kept thinking, ‘Man, this kid is 5.’ ”

Murray scored five first-half touchdowns that day, a dominant performance that wasn’t out of the ordinary for him. In seven years in the Lewisville Football Association, Nelson recalls Murray’s teams losing only a single game.

The coach of those teams was Murray’s father, who starred at quarterback for Texas A&M in the mid-1980s and has since established himself as one of his state’s best quarterback instructors. Kevin Murray had his son running a spread offense, displaying textbook footwork and drawing comparisons to Michael Vick by the time the boy was 9.

“I've been out here 20 years, and he is the best kid to come through our program by far,” Nelson said. “Nobody could stop him. He was that special.”

Kyler as an eighth grader

The talent gap between Murray and his peers hadn’t decreased much by middle school. He was a threat to score whenever he touched the ball — sometimes even against his coach’s wishes.

One time during Murray’s eighth-grade season, his team faced a rare fourth-and-long deep in its own territory. Huffines Middle School coach Heath Naragon hadn’t bothered to install a punt formation while he had Murray under center, but he had his dynamic quarterback practice quick kicks in case of fourth-and-long emergencies like this one.

Naragon called for the quick kick from the sideline. Murray responded with a confused look.

“Punt the ball! Punt the ball!” Naragon shouted. This time, Murray appeared to understand.

Murray caught a shotgun snap, took a couple steps backward to give himself room to kick like he and Naragon had practiced and then paused to survey the field. It was then that Murray disobeyed his coach and began to freelance, juking one defender, then another, then a third, before bolting for an 85-yard touchdown run.

When Murray got to the sideline, Naragon couldn’t decide whether to scream at his quarterback or to hug him.

“What the heck were you doing?” Naragon asked. “Didn’t I tell you to punt the ball?”

“Yeah, but I knew I could at least get a first down,” Naragon recalls Murray responding.

“Do what I tell you to do next time,” Naragon concluded. “But great job, man. Heck of a run.”

Hoping to prepare Murray for the pass-happy offense he’d run at the next level, Naragon installed a base version of the Air Raid system that coach Dick Olin used at Lewisville High School. Every week, Olin and Naragon would challenge Murray by adding a few more wrinkles from Lewisville’s varsity playbook. Every week, Murray would show he grasped the new concepts and ask for more.

“By the end of the season, we were running an offense that was varsity-level,” Naragon said.

“I was a 22, 23-year-old guy coming out of college, and I was thinking, ‘Wow this coaching deal is pretty dang easy.’ Now I know that Kyler was an anomaly. It takes most kids years to be able to understand those concepts, let alone execute them.”

Kyler in Little League

When Murray wasn’t weaving through defenders on Lewisville’s football fields, he often could be found terrorizing pitchers on the town’s baseball diamonds.

As early as Little League, he flashed hand-eye coordination at the plate, athleticism in the field and sprinter’s speed on the base paths.

There was no such thing as a routine ground ball off Murray’s bat. Infielders learned they had to charge the ball to have any hope of throwing him out at first.

“One time we were playing in a Perfect Game tournament and he hit a two-hopper back to the mound,” said Sam Carpenter, Murray’s travel ball coach with the Dallas Mustangs. “The pitcher fielded it cleanly and he still beat it out.”

It got only tougher for pitchers if Murray reached base. He’d often steal second. Then third. It wasn’t unheard of for him to seize the chance to steal home either.

“I was always one of the faster kids on every team I played on, and he could run circles around me,” said childhood friend Josh Abalos, a youth baseball teammate of Murray’s from age 8-12. “It didn't look normal for a kid that age to move that fast.”

Murray’s speed was reminiscent of his uncle, a former first-round draft pick of Cleveland in 1989 and the San Francisco Giants in 1992. Calvin Murray tallied more than 50 stolen bases in a single season twice in the minor leagues and later spent parts of six seasons in the majors because of his speed on the base paths and ability to cover ground in the outfield.

Said Carpenter, who coached both Murrays, “At an early age, you could see [Kyler] was going to be at least Calvin.”

Kyler on the basketball court

As Murray piled up touchdowns and base hits, word of his athleticism spread to coaches in other sports.

Nate Brewer, coach of the Texas Tar Heels basketball program, began showing up to Murray’s youth football games to try to persuade the then-7-year-old to give hoops a try.

Murray was a defensive menace from the start in Brewer’s full-court press, but not every aspect of his transition to basketball was an instant success. He’d careen down court so fast after stealing the ball that his fast-break layup attempts would carom wildly off the backboard and bounce toward mid-court.

“He was full-go, all the time,” Brewer recalled with a laugh. “I had to teach him how to slow down to make a layup. That was like our first month of practice.”

In three years with the Texas Tar Heels, Murray blossomed into a point guard with an explosive first step to the basket, active hands and a ferocious competitive streak. He’d vie for rebounds against the tallest kid on the floor, skid across the court diving after a loose ball and sob uncontrollably anytime his team suffered a rare loss.

Basketball was always Murray’s third sport, but he never treated it that way. In fact, he once pushed back against his father when Kevin Murray suggested he miss a basketball game that conflicted with a baseball tournament.

“Dad, we’re in the championship,” Brewer recalls Murray saying. “I’m not missing the championship. I'm missing the baseball game, and I'll get them to the championship game tomorrow.’”

While Murray made a shrewd choice focusing exclusively on football and baseball after middle school, Brewer wonders how far his former pupil could have gone had he ever seriously pursued basketball. Brewer is adamant that Murray would have played Division I basketball at minimum — maybe high-major Division I if he added a consistent jump shot to his repertoire.

“He was probably the best pure athlete I've ever had,” Brewer said.

Kyler playing chess

Two of the most meaningful victories of Murray’s childhood didn’t happen on the football field or the baseball diamond.

They came with Murray behind a chess board inside the library at Degan Elementary School.

When Murray was in fourth grade, science teacher Michael Staten invited him to join Degan’s chess club. Once a week after school, Murray tried to outwit and outmaneuver his classmates in chess as decisively as he did defenses on the football field.

Murray brought the same enthusiasm and competitiveness to chess that he did to every sport he played. Though the chess club had more than 100 members, Murray won its end-of-the-year single-elimination tournament as a fourth grader and then defended his title as a fifth grader.

“I was the chess club adviser at that school for 18 years, and he's the only kid who ever pulled that off,” Staten said with a chuckle. “He was really interested in chess and he was really good too.”

Murray could think three or four moves in advance like every good chess player, but where he excelled was improvising when his plan went awry. The ticking clock never fazed Murray. He’d calmly survey the board, rethink his strategy and make a logical move.

Anytime anyplace. 🥋 pic.twitter.com/X6c4hRixs9

— Kyler Murray (@K1) August 2, 2020

Now a dozen years removed from elementary school, Murray still regularly plays chess. His former chess club adviser says that the aggressiveness and anticipation Murray displays in chess mimics how he attacks defenses on the football field.

“Whatever the situation, he could figure it out,” Staten said. “He was a very good reactionary chess player.”

Kyler as a freshman

As good as Murray was at most everything he tried, football remained his calling.

Seldom was that more apparent than the night he threw for more than 500 yards while leading Lewisville’s freshman team to a rout of overmatched Plano East.

The way Olin remembers it, Plano East’s coach was mad that Murray kept throwing deep into the fourth quarter. Olin says he told him, “Coach, I apologize, but the one thing you have to understand is we were doing you a favor by throwing it on every down.

“If Kyler is throwing the ball, maybe your secondary might knock down a ball or maybe one of our receivers might drop it. But if he takes off and runs, you have no one who can catch him.”

The summer after Murray’s freshman year at Lewisville High, his family moved to another Dallas suburb. Not only was Allen closer to many of the quarterbacks that Murray’s father trained, it was also home to a high school football powerhouse only four years removed from its first state championship.

When Murray introduced himself to some of Allen High School’s receivers, he caught them by surprise with his confidence that he’d win a starting job as a sophomore. Cole Carter remembers thinking, “This kid doesn’t quite know what football is like over here.”

Everything changed when Murray threw to his receivers for the first time. It soon became clear that the slender, undersized newcomer wasn’t so delusional after all.

“The first time I caught his balls, he almost ripped my head off with an out route,” Carter said. “It was pretty apparent even then that this kid was a little different.”

The stage for Murray’s varsity debut was high school football’s equivalent of Broadway. More than 22,000 people filled Allen High School’s new $60 million stadium in 2012 to watch the home team take a crack at reigning Texas state champion Southlake Carroll.

The Allen coaches intended to have Murray enter the game for only a series in each half until an injury to the starter altered their plans. Murray responded with poise and confidence and helped Allen finish off a 24-0 shutout even though he’d met his teammates only a few weeks prior and he still didn’t know many of the signals or formations.

“It was then that we realized there wasn't anything that was going to bother this kid,” former Allen offensive coordinator Jeff Fleener said. “It just shows he’s wired differently than other kids.”

Kyler becomes a leader

The opening drive of Murray’s junior season ended in catastrophe.

One of Murray’s first passes bounced off his receiver’s chest and into the arms of a Southlake Carroll defender. The defender sprinted down the sideline for a pick six, giving revenge-minded Southlake Carroll an early lead in a rematch of the previous year’s season-opening showdown.

With Allen’s receivers moping, Murray seething and the opposing sideline in a frenzy, Fleener feared the nightmare start could snowball. He struggled to find the right words to restore his offense’s confidence until Murray stood up, crumpled his water cup and brazenly announced, “These guys are trash. If we don’t throw for at least 400 yards on them, I’m going to be pissed.”

“Every receiver on the other side of me perks up and hops off the bench,” Fleener said. “Sure enough, he did exactly like he said. He threw for like 420 yards and rushed for another 100 and we won the game [49-27].”

That sideline exchange between Murray and Fleener was symbolic of a subtle change that occurred between the quarterback’s sophomore and junior seasons. No longer was he the quiet newcomer who deferred to older players. This was now his team to lead.

Seldom did Fleener speak first during his weekly Monday morning meetings with Murray. The quarterback had already studied film of the upcoming opponent and would tell his offensive coordinator which cornerback he thought he could target or which safety had a tendency to bite on play-action.

Murray never needed a pregame speech or a pump-up playlist to psyche him for a game — and he couldn’t understand why any of his teammates did either. This was a kid who would be livid the rest of practice if the offense lost to the defense in a 7-on-7 drill.

Fleener also didn’t have to worry about scolding a player for loafing in practice or committing a foolish penalty during a game. Murray would get in their face right away to make sure they knew that wasn’t acceptable.

“If a kid didn't run hard enough or didn't run a route right, Kyler was going to let him know — and I mean he was going to let him know in all the interesting and colorful ways you can,” Fleener said.

Kyler to the rescue, Part I

The narrowest escape of Murray’s high school career required an unfathomable fourth-quarter comeback.

Allen trailed DeSoto by 15 points with eight minutes left in the 2013 state semifinals. The situation was so bleak that on Allen’s side of Mesquite Memorial Stadium, fans clad in red and blue streamed toward the exits.

Having surrendered more than 100 rushing yards and two touchdowns to Murray in the previous year’s state semifinal, DeSoto entered the rematch determined not to let the quarterback beat them a second time with his legs. DeSoto coach Claude Mathis ditched the 3-4 scheme that his team had used all season and switched to a new defensive look intended to eliminate Murray’s rushing lanes and prevent him from escaping the pocket.

In addition to loading the box with eight defenders, Mathis ordered his interior linemen to stay in their lanes and his defensive ends to stay outside. Mathis also used a linebacker as a spy, meaning that his responsibility was mimicking Murray’s actions and tackling him if he took off to run.

“What we wanted to do was form an umbrella,” Mathis said. “We wanted to take the running lanes away from him, but at the same time still rush him.”

The new look confounded Murray for most of the game. He had prepared to attack a traditional 3-4 scheme, and now he was facing something else entirely.

The game changed when Fleener realized that DeSoto’s free safety was also keeping an eye on Murray even though his responsibility was to cover the deep middle. Murray hit receiver Jalen Guyton on a deep post pattern, and all of a sudden Allen was back within one score.

Murray exploited the free safety once more in the game’s final minute. He dropped back with his eyes to the right to draw the free safety that way, then escaped the pocket left and found only green grass between him and a go-ahead touchdown.

“It was one of those moments when you knew this kid was something special,” Fleener said. “After that, I think our kids knew we were never out of a game as long as we were snapping to him.”

Allen eliminated DeSoto from the playoffs again Murray’s senior year, this time on a go-ahead field goal in the game’s dying seconds. To this day, Mathis maintains that Murray cost his team at least two state championships.

“Those last two for sure,” Mathis said. “He’s the best quarterback I ever faced.”

Kyler to the rescue, Part II

Students from rival schools eventually grew sick of Murray tormenting them on the football field year after year.

As a result, they would pack the bleachers for baseball games against Allen in hopes of seeing Murray chase a high fastball or flail at a slider in the dirt.

“Student sections would come out in droves just to heckle him,” Allen baseball coach Paul Coe said. “Two for four is a really good day in baseball, but they had a lot of fun the two times they got him. If he struck out and grounded out, that's all they remembered.”

Of course Murray had plenty of fun at the expense of his opponents during baseball season too. The muscle Murray added during high school helped him blossom into a home run threat to go along with his elite speed on the basepaths.

“He hit one of the hardest balls I've ever had hit right at me,” said Abalos, who played shortstop for a rival high school. “It damn near knocked my glove off. I had to take my glove off and shake my hand afterward. It hurt that bad.”

The at-bat that left Murray’s high school baseball teammates awestruck occurred during a win-or-go-home playoff game in May of his senior year. Murray arrived at the baseball diamond in the middle of the second inning after taking his SAT.

“By the time he got there, we were behind by one run,” Coe said. “He stopped to talk to people in the parking lot, and we're out on the field like hurry your butt up!”

Murray changed into his baseball uniform in the dugout, but he didn’t even have time to tie his shoes or take any practice swings before it was his turn to bat. Undaunted, he drove the second pitch he saw for an RBI double off the wall, sparking an onslaught of 10 consecutive Allen runs.

“His shoes are falling off as he’s running to second, and he acted like it was no big deal,” Carter said with a laugh. “It made the rest of us who are out there taking batting practice and stretching our butts off feel really good.”

Kyler threads the needle

The play that Murray’s high school football coaches say typifies his success probably isn’t one that most outsiders would expect.

It happened during an innocuous blowout victory, and on the surface it looked like Murray had made a mistake.

Late in a 44-10 victory over Hebron High, Fleener called a play that allowed Murray to choose between one receiver running a wheel route and another running a skinny post. The wheel route was wide open, but Murray lasered the skinny post pass into tight coverage instead.

“Why in the world would you try to jam the ball in there when you know we have the wheel route wide open?” Fleener asked Murray during a film session a couple days later.

Murray responded that Allen was already up four touchdowns and that extending the lead didn’t matter that late in the game. He preferred to take the opportunity to see if he could beat tight coverage on the skinny post because that’s what he’d need to do against DeSoto, Euless Trinity or another potential playoff opponent.

“I was playing checkers, and he was playing chess,” Fleener said. “He realized we were up 28 points and he was getting a live rep against another defense that was better than what he was going to see against a scout team. Why not use that time to see if he could make that throw? I was like, ‘Who is this kid?’ His maturity and understanding were off the charts.”

More from Yahoo Sports: