Are These Foods Actually from Where Their Name Says?

Brussels sprouts? Scotch eggs? Swedish meatballs? Which food names can you trust?

Are the following foods actually from the country referenced in their names?

1. Brussels Sprouts

Kind of

The ancestors of modern-day Brussels sprouts were likely first cultivated in ancient Rome, not Brussels. Although the first written record of these miniature, cabbage-like vegetables came in 1587, present-day varieties are thought to have been growing in Belgium’s capital since the thirteenth century, and the vegetable is popular in Belgium, but Belgium is not one of the leading world producers of Brussels sprouts.

Depending on which style guide you follow, the B in “Brussels sprouts” can be capitalized or lowercase. The Chicago Manual of Style recommends lowercase because Brussels sprouts often aren’t from Brussels, so their editors don’t view “Brussels” as being used literally to refer to the city, but the AP Stylebook says to capitalize “Brussels.”

For our first ruling, this one is kind of waffle-y. Brussels sprouts didn’t originally come from Brussels and the city isn’t a big supplier of the little cabbages, but they probably got their name because they were so popular in Brussels. If forced to choose, we’d have to say the name isn’t fake.

2. Scotch Eggs

No

The Scotch egg is a dish made from a hard or soft-boiled egg that is encased in sausage, coated with breadcrumbs, and deep fried or baked. Dotting the aisles of English supermarkets and gas stations, Scotch eggs are an undoubtedly British staple, though they do not hail from Scotland as their name suggests.

The treat has varying origin stories; one states that the Piccadilly outlet of the English department store Fortnum & Mason created the snack for its wealthy customers to munch on as they traveled. One theory is that officers of the Scots Guards who were stationed near the store particularly liked the dish, and that’s where it got its name. Another theory claims that the egg dish was created in Yorkshire at a restaurant called William J Scott & Sons where it was originally called “Scotties.”

Some people speculate that the family name “Scott” may be the origin of the name “Scotch eggs.”

According to food historian Annie Gray, a likely origin of the snack is that it may be an alteration of nargisi kofta, a dish that was brought to England either by soldiers returning from India or by the British Raj. Nargisi kofta is similar to Scotch eggs in that they’re made from hard-boiled eggs that are covered in minced meat and laid over gravy. The “Scotch” in this food name is fake since the dish has nothing to do with Scotland.

3. Belgian Waffles

Sort of

First introduced to the United States at the 1962 World’s Fair in Seattle, Belgian waffles did not rise to prominence until two years later, when the Vermersch family began selling their homemade Brussels waffles at the 1964 World's Fair in New York.

The Vermersch family, who hailed from Belgium, first referred to their waffles as “Bel-Gem” waffles, because they did not think that Americans knew where Brussels was. So this dish isn’t from Belgium, but was popularized by Belgians. We’ll call it not quite real and not quite fake.

4. Kiwi Fruit

No

Though many of us know it as a delicious fruit, the word “kiwi” has several different meanings. The term can describe New Zealand natives, the New Zealand dollar, or the furry, brown bird that shares a similar appearance to the fruit so many of us love. Despite association with New Zealand, this juicy fruit is actually native to China, and was originally called the “gooseberry.”

Kiwis were first planted in New Zealand in 1906, after Mary Isabel Fraser brought back seeds from the city of Yichang, China. The seeds were then planted in Wanganui by nurseryman Alexander Allison, and the first Oceanic kiwi fruit grew in 1910. We'll call this one fake since the fruit didn't originate in New Zealand.

5. French Toast

No

The first known French toast-like dish appeared in “Apicius,” a cookbook featuring recipes from the first through fifth centuries A.D. The French don’t call this dish “French toast.” Before acquiring its current name, “pain perdu” or “lost bread,” the French originally referred to French toast as “pain a la romaine”—“Roman bread.” So where does the “French” in “French toast” come from?

A widespread—though uncorroborated—tale is that Albany, N.Y. innkeeper, Joseph French created the recipe in 1724 and named it after himself. There are many other competing and equally unverified origin stories, but none of them puts the origin in France, so we’ll call “French toast” another fake food name.

6. French Dressing

No

Although the oil and vinegar base of French dressing is popularly used in vinaigrettes in France, what Americans refer to as “French dressing” is definitely not French. American French dressing is a zesty, creamy sauce and ranges from orange to red in color.

It consists of mayonnaise, ketchup, paprika, pepper, and that oil and vinegar base, and although this is anecdotal, a scan of online comments suggests the French people find this dressing disgusting. The origin of the word “French” in the name is a mystery, but you can add French dressing to our list of fake food names.

7. Russian Dressing

No

Russian dressing (often confused with its sweeter cousin, Thousand Island dressing) is a red-orange, creamy blend of various spices. Created in the 1910s by New Hampshire native James E. Colburn, Russian dressing is tangy, often containing mayonnaise, horseradish, and chili sauce or ketchup.

Some food historians believe the dressing was deemed “Russian” because early versions contained caviar—a Russian delight. Others hypothesize that pickles, an entirely different, and much less expensive ingredient, were the source of the Russian component.

Perhaps the simplest theory is that the dressing was created simply to accompany Russian salad — a potato salad dish popular in Russian cuisine. Since the salad dressing is at best loosely associated with Russia, we’ll call this another fake food name.

8. Swedish Meatballs

No

If you have nibbled on meatballs after browsing through home decor at IKEA, köttbullar, as they’re called in Sweden, may seem like a Swedish classic. However, these meatballs are actually Turkish.

Sweden’s official Twitter account tweeted that the dish had been a favorite of King Charles XII, who likely discovered köttbullar when he fled from Russia to the Ottoman Empire after an invasion gone wrong.

The tweet caused a social media uproar and many Turks petitioned Sweden to begin calling its meatballs by their rightful name: köfte. It’s a great story, but now we have to add “Swedish meatballs” to our list of fake food names.

9. Vienna Sausages

Probably no

In the United States and other English speaking countries, Vienna sausages are soft sausages made of beef and pork that are packaged in broth filled cans. The European versions of these sausages are uncanned and have conflicting names.

In Austria, they are called “frankfurters,” after the city of Frankfurt, Germany. In Germany, they are referred to as “weinerwurst” or “wieners,” the term for residents of Vienna. The first entry in the Oxford English Dictionary for the Anglicized version, “Vienna sausage,” is from 1958. So, which city actually created the Vienna sausage? It’s hard to say.

One theory is that a Frankfurt butcher created the first frankfurter but later moved to Vienna, where residents paid homage to his German roots—hence the Austrian term, “frankfurter.” Since it’s hard to definitively tie the origin of Vienna Sausages to Vienna, we’ll put this one in the “probably fake” category.

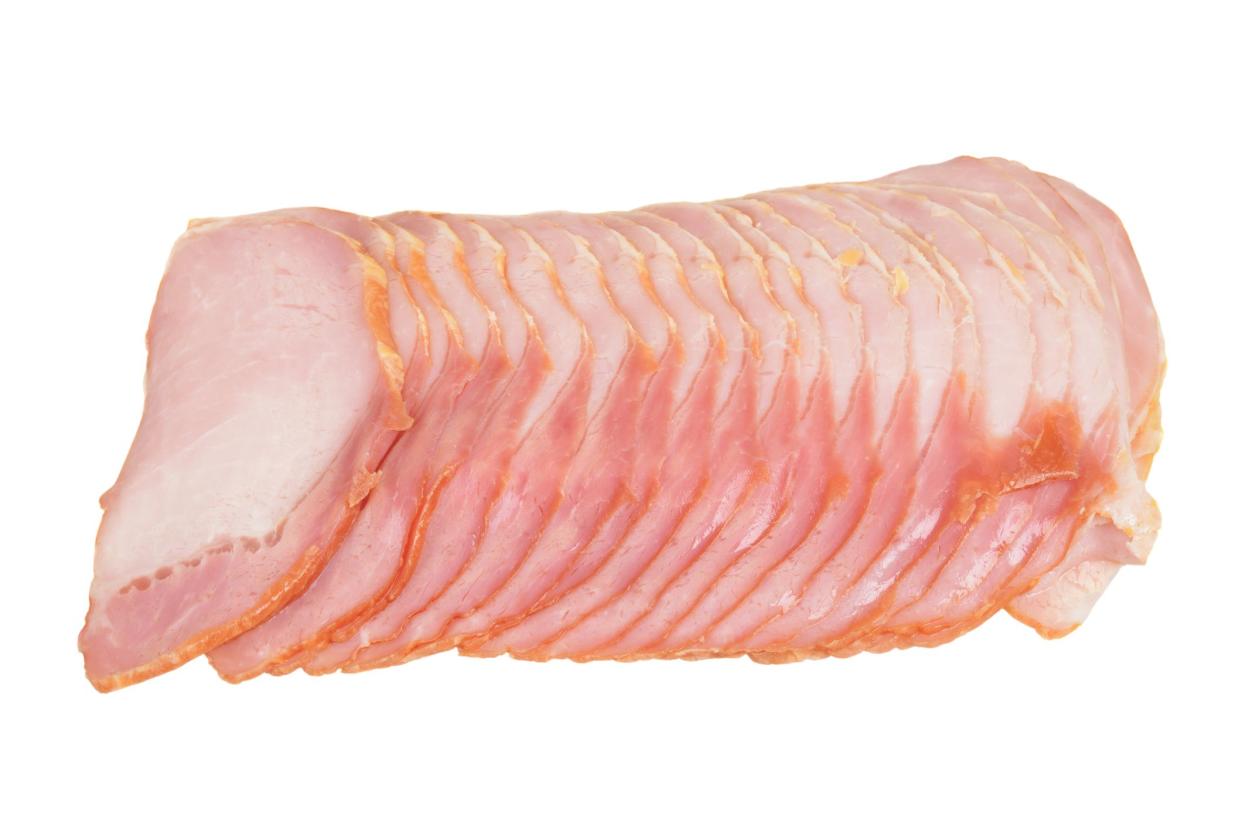

10. Canadian Bacon

No

In the United States and Canada, the term “bacon” refers to a type of thinly sliced, salt cured, often smoked meat usually cut from the sides of pigs. So what exactly is “Canadian bacon” if our Canadian counterparts eat the same bacon as we do?

“Canadian bacon” or “Canadian-style bacon” is meat cut from the backs of pigs and looks a lot like ham. In Canada, this meat is called “back bacon” and is sliced into thick circles. And with that, we end with another definite fake food name because Canadian bacon isn’t exclusively from Canada and didn’t originate there.

Reference.com speculates that Americans call back bacon “Canadian bacon” because there was a shortage of regular bacon (the strips cut from the sides of pigs) in the mid-1800s, and back bacon was brought in from Canadda to meet the demand.

11. Buffalo Wings

Yes

Omnipresent at fast food restaurants and tailgates across the nation, buffalo wings are a definitively all-American appetizer. Created in 1964 by Teressa Bellissimo, these deep-fried chicken wings are tossed in a red-orange sauce that is sure to pack a punch.

Bellissimo is said to have served the first batch of wings “with a side of blue cheese and celery because that’s what she had available” — a coincidentally perfect contrast to the spicy sauce on the wings.

The Bellissimo family disputes why the wings were invented; one story states that they were resourcefully created to make use of chicken wings, while another claims that they were made as a late night snack for Teressa’s husband.

We know that this messy food is made from chicken not bison; the "Buffalo" in this real food name comes from Buffalo, New York, where Teressa Bellissimo invented and first sold the wings.

12. Worcestershire Sauce

Yes

This difficult to pronounce sauce was accidentally invented in the early 1800s when nobleman Lord Sandys enlisted chemists John Lea and William Perrins to recreate a sauce he had come across on a trip to Bengal.

Much to the chemists’ dismay, the sauce did not turn out to be tasty, so they stored it away in their cellar in, you guessed it, Worcester.

The duo rediscovered the jars a few years later, and were pleasantly surprised to find that the mixture had aged into a delicious sauce.

While this liquid is produced by many brands today, the exact ingredients that Lea and Perrins used “remains a closely guarded secret and only a privileged few know the exact ingredients.”

13. Sriracha Sauce

Yes

Sriracha sauce gets its name from the coastal city of Si Racha, Thailand. According to his great-granddaughter, Gimsua Timkrajang was the first person to create the chili-garlic condiment, craving a sauce that combined all of the sweet, salty, and sour flavors he encountered on work trips to Myanmar, Cambodia, and Laos.

The sriracha that most Americans eat today is derivative of Timkrajang’s recipe, likely westernized to fit American tastes.

This article originally appeared on QuickAndDirtyTips and was syndicated by MediaFeed.