Florida’s a battleground but not for votes. It’s the civil rights left vs. anti-woke right

As protesters marched to the Florida Capitol on Wednesday for the second rally in three weeks to oppose what they say is Gov. Ron DeSantis’ “assault” on Black history, the state’s battle over the future of education started to take shape as a war over the future of civil rights in America.

On one side is DeSantis and the Republican-led Legislature — with coaching from Christopher Rufo of the conservative Manhattan Institute. They vow to move the nation to a pre-1960s America with “a new conservative counter revolution.” Their goal: ending what they say is a “neo-Marxist” focus on “wokeness” in education, corporate America and government that discriminates against individuals.

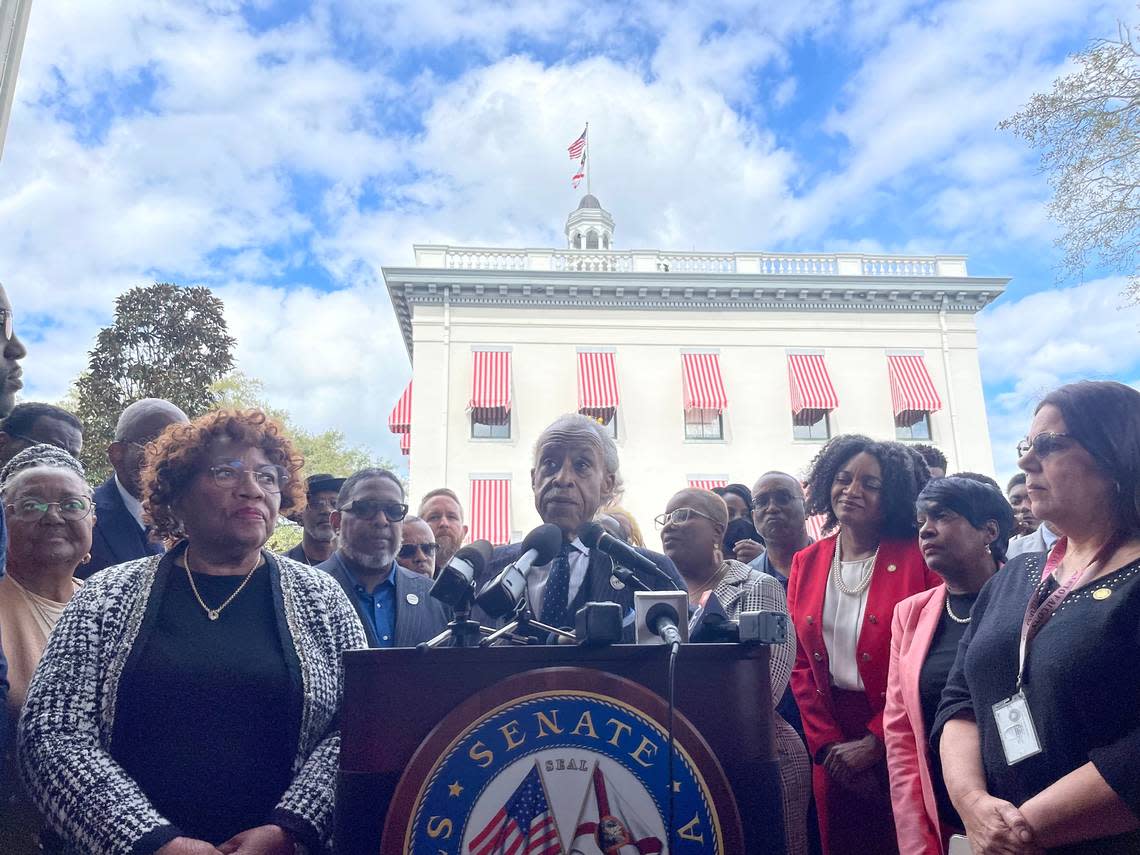

On the other side are Florida’s Black leaders and national civil rights activists like Al Sharpton. They vow to ignite voter energy and unleash a grassroots movement to remind people that “this is not 1963. It’s 2023.”

Their goal: halting what they see is the effort to reverse the gains of the civil rights era, particularly as it relates to education and voting — which they have long viewed as the two pillars of a multiracial democracy.

The conflict could have national implications but, right now, DeSantis has the upper hand, and the Black pastors who assembled on the Capitol plaza with hundreds of their supporters took note.

“We are here today to serve notice on you that we will not stand for it,” bellowed the Rev. Rudolph McKissick Jr., pastor at Bethel Church in Jacksonville, within shouting distance of the governor’s office. “We are not just marching, but we are coming to affect change. ... We’re not going to let you determine how our story gets told.”

The leaders talked about voter registration drives and get-out-the-vote efforts. They threatened legal challenges and suggested Black athletes could boycott Florida universities. They vowed to teach “truthful Black history” in churches, community programs and college clubs. And they warned of a national effort to have their supporters protest wherever DeSantis goes if he launches a presidential campaign, as expected.

Sharpton, the talk show host and civil rights activist, told the crowd that Florida may be DeSantis’ “domain” but he could face “a real fight” with a broad coalition of opponents outside of his home state.

“He needs to understand that he will have resistance all over this country if he keeps messing with Blacks, LGBTQ and women,’’ he said.

Fighting against a regression in civil rights

The leaders pointed to what they say is DeSantis’ history of being anti-Black: his strong-arming the Legislature to pass a redistricting map that eliminated two congressional districts held by Black Democrats; his push for legislation aimed at criminalizing peaceful protests; his plan to ban colleges and universities from offering diversity, equity and inclusion programs; his ban on critical race theory; his law restricting the instruction of race relations in classrooms; and his rejection of the College Board course on African-American studies.

“This governor is trying to turn back the hands of time,’’ said Ben Frazier, a Jacksonville activist and president of the Northside Coalition as he spoke to protesters gathered at the Bethel AME Church in Tallahassee. “He’s a one-man wrecking machine.”

While DeSantis may have one of the highest profiles in the battle, he is not the only Republican leader who has engaged in the fight.

According to the UCLA School of Law’s tracking project, at least 183 local, state and federal government entities across the country have introduced bills, resolutions, executive orders, opinion letters, statements or other measures to roll back equity and inclusion measures and block discussions about race and systemic racism.

“This is not just a Florida problem,’’ said state Sen. Shevrin Jones, D-Miami Gardens, at a Jan. 25 rally to announce a threatened lawsuit against the governor. “Florida is just a petri dish. But people from across the country should be concerned. ... If it can happen in Florida, it can happen in Tennessee. It can happen in Colorado.”

A new Florida export

Exporting Florida’s initiatives to other states, especially Republican-governed ones, is precisely the plan for Rufo and other DeSantis allies.

Shortly after DeSantis named Rufo, a conservative activist who is an architect of the anti-woke crusade, to the board of the New College of Florida last month, he quickly posted a video titled “The Conservative Counter-Revolution Begins in the Universities.” In it, Rufo explained how he will use the “strategies” of Marxist theorists of the 1960s and change public policy from the top down to “recapture institutions” from “bureaucratic morality.”

“It starts with this hostile takeover of the New College of Florida and on the beaches of Sarasota,’’ he declared. “And if we are to be successful, I think that we’re going to create a model for red state governors all over the country.”

In March 2021, Rufo acknowledged the desire to create the code words for the movement that could be used to reflect common grievances of Americans. He began with the term: “critical race theory.”

“The goal is to have the public read something crazy in the newspaper and immediately think ‘critical race theory,’ ” he wrote on Twitter. “We have decodified the term and will recodify it to annex the entire range of cultural constructions that are unpopular with Americans.”

Critical Race Theory is “a euphemism for equity, social justice, diversity and inclusion and culturally responsive teaching,’’ Rufo argued in another video, and those are things embedded in our institutions. He suggested that the changes to public education are intended to “put guardrails on what kind of values and ideologies you can transmit” and to “exclude certain ideas — like one race is inherently superior to another race, or you should feel guilty on behalf of your ancestry or your racial identity.”

Those who study the discipline of critical race theory, however, say the goal is not to suggest individuals are racist but instead to shift the emphasis to public-policy tools that can be used to create equity and freedom for all.

“Rufo, the Heritage Foundation, the Manhattan Institute, all have a rhetorical strategy that tries to broadly reframe civil rights remedies as themselves a threat to civil rights,’’ said Jonathan Feingold, a history professor and expert on anti-discrimination law at Boston University. “If you are comfortable with inequality, and would prefer a system that retreats to the hierarchies of old, then it makes sense to try to villainize and delegitimize modest efforts to account for all the ways in which race and racism continue to operate in American society.”

If there is a rallying cry for this revolution, however, it is DeSantis’ declaration on his reelection night that Florida is “where woke goes to die.”

What does ‘woke’ really mean?

The governor has used “woke” to describe the Advanced Placement African-American Studies course, the College Board, Walt Disney Co., the NCAA, math books, Hillsborough County State Attorney Andrew Warren, school boards, universities, cruise ship companies and businesses that offer diversity, equity and inclusion training.

But what the governor means precisely is open to interpretation.

Like Rufo, DeSantis equates “wokeism” to Marxism, the political and economic theories that formed the basis of communism. But he offers no examples.

“I think what you see now with the rise of this woke ideology is an attempt to really delegitimize our history and to delegitimize our institutions,” DeSantis said last year as he signed into law the Stop W.O.K.E. Act, which restricts race-based conversations in schools and businesses. “And I view the wokeness as a form of cultural Marxism.”

But civil rights leaders say it is DeSantis who is delegitimizing history with conduct that parallels what happened during the era of Jim Crow by reversing progress.

After the Civil War and slavery was abolished, Blacks were elected to state and local offices and, for the first time, made strides in business and education. But the movement to “deconstruct reconstruction” reversed their gains as state and local Jim Crow laws legalized racial segregation and suppressed Black voting.

Jim Crow laws were outlawed in 1964, with the signing of the Civil Rights Act and the 1965 passage of the Voting Rights Act. But the intense and sustained backlash against Reconstruction, which lasted nearly a century, “was a period of unrivaled racial terrorism and your rights were determined by the state you were in,’’ Feingold said.

“We see the same thing happening now with this governor and his attack on things that are Black,’’ said Frazier, the Jacksonville activist.

Feingold suggests that DeSantis is trying to wrap together the public’s frustration with racial divisions when he uses the term “woke.”

That became clear when Ryan Newman, the governor’s general counsel, was asked under oath what “woke” meant. Testifying in the court case brought against the governor by the ousted Hillsborough County state attorney, Newman answered: “Generally, the belief there are systemic injustices in American society and the need to address them.”

“Newman placed DeSantis on the side of injustice,” Feingold wrote in an essay for The Conversation. Feingold said DeSantis could be called an “injustice denier.”

DeSantis says America is opportunity, not systemic racism

The DeSantis camp not only denies that institutional racism and systemic injustices exist in the United States, it argues that the remedies to racial inequities — such as programs that encourage diversity, equity and inclusion — are themselves violations of anti-discrimination laws and other civil rights protections.

In an April 2021 interview with Laura Ingraham, DeSantis was asked if he thought systemic racism exists. The governor quipped that it was “a bunch of horse manure.”

“I mean, give me a break,’’ he said. “This country has had more opportunities for people to succeed than any other country. It doesn’t matter where you trace your ancestry from.”

Jones, the state senator, echoed the words of many Black leaders when he described the governor’s policies as intended to roll back advances in racial justice in America as the country becomes increasingly less white and more racially diverse.

“It’s not just about AP history,’’ Jones said. “The fight is against this strong uprising of racism from people who are seeing the shifting of America.”

Herald/Times Tallahassee Bureau reporters Ana Ceballos and Lawrence Mower contributed to this report.

Mary Ellen Klas can be reached at meklas@miamiherald.com and @MaryEllenKlas