Flashback to the Detroit Stars: Baseball baron lived large, died suspiciously

One wet, sloppy afternoon in Depression-era Detroit, Tenny Blount reportedly lost his balance and tumbled down a flight of basement stairs — a fatal plunge that serves as a kind of metaphor for his own fall from grace in the early years of Negro League baseball in Detroit.

The snazzy numbers racketeer is an obscure historical figure in local baseball circles. But in palmier days as the owner of the Detroit Stars, Blount oversaw one of the few stable franchises in Rube Foster’s Negro National League. Moreover, as league vice president, he served as Foster’s chief lieutenant, helping to make the circuit an important symbol of Black success in Jim Crow America.

“I agreed to take some of the players and start a ballclub in Detroit,” Blount would later tell the Chicago Defender, describing his initial association and eventual falling-out with Foster. “I had honor and character and believed most of the men possessed the same. Crookedness of heart had never crossed my mind.”

John Tenny Blount was born in Alabama in 1873 and moved to Chicago as a young man. There he gained notice for restoring an old dance pavilion, which he used as a front for gambling activities. He moved to Detroit in 1914 to manage the Union League clubhouse on Grand River, overseeing many high-stakes card games. At the same time, he established himself as a major player in Detroit’s numbers racket.

Numbers, also known as policy, was an illegal daily lottery especially popular in Black neighborhoods. At 600-1 odds, a winning dime bet paid $60, about equal to the usurious monthly rents many residents were paying their white landlords. Most folks just bet a penny or two, but those pennies added up for Detroit’s policy kings.

Numbers racketeers, euphemistically called “sportsmen” or “realtors,” were a source of capital in the Black community. John Roxborough, for example, co-managed heavyweight champ Joe Louis during his climb to fame and was well known as a numbers kingpin.

Instant success

Blount’s proven management skills, reputation for honesty, and liquidity attracted Foster as he was preparing a trial run for his league in 1919. But his background in baseball is fuzzy. He doesn’t appear to have played organized ball at any point in his life, though he may have booked games in the past at Mack Park, the venue at Fairview and Mack Avenue that the Stars would call home throughout the 1920s. His involvement was more of a moneymaking proposition — a business, not a passion.

Blount agreed to invest with Foster in placing a team in Detroit, though his percentage of ownership is unknown. As part of their agreement, Blount was obligated to pay Foster 10% of the gross receipts of all games played by the Stars. This was on top of the standard 10% all teams paid into the league operating fund.

Foster, who, for years, had owned and managed one of the top independent clubs in the country, stocked the Stars with several players from his Chicago American Giants.

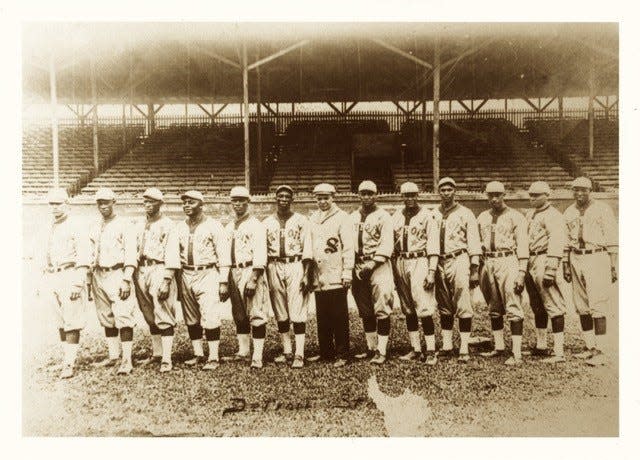

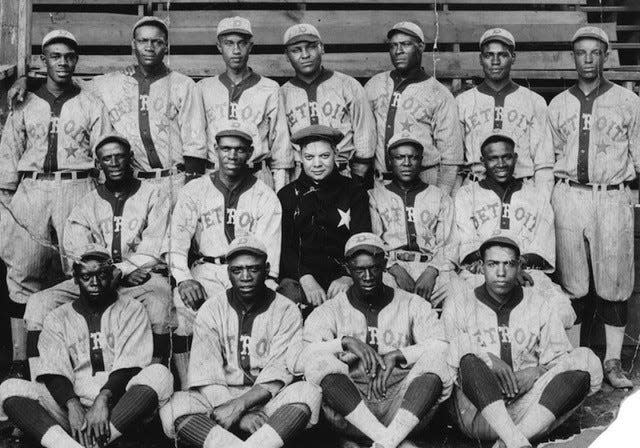

The Detroit Stars opened the 1919 season by defeating the city’s semipro champs, the Maxwells, on Easter Sunday. Although no formal records were kept, the Free Press stated that the new team in town had racked up 44 victories “against some of the best clubs in the country.”

After this successful test run, the Negro National League was formally organized in February 1920. The Stars thrived under Blount’s management, playing competitive ball and turning a profit every season. The roster featured two future Hall of Famers, outfielder Turkey Stearnes and pitcher Andy Cooper.

“Five years ago Tenny Blount was unknown in the baseball world,” the Defender noted in 1924. “Today he is one of the best known and most popular owners that the game has produced. In five years he has built up a most powerful baseball machine.”

During his 20 years in Detroit, Blount always stayed close to Gratiot and St. Antoine, in the heart of a vibrant strip of cabarets, theaters, restaurants, and clubs known as Paradise Valley. He lived large. He was especially partial to “sparklers,” the large diamonds that adorned his fingers and necktie, and fast cars. He owned racehorses in Kentucky and attended prizefights and derbies around the country. Blount often entertained Foster at his well-appointed apartment on Gratiot.

‘Tired of giving my money away’

But in 1924, their once convivial relationship soured. Although Blount had bought out Foster and now owned the Stars outright, he was still beholden to their original agreement. The booking fee was tolerable when things were going well. But a series of disastrous rainouts, competition from the crosstown Tigers (who had just expanded Navin Field), and his recent wedding caused the cash-strapped Blount to protest.

Foster, in failing health, was irritable and irrational. When Blount arranged a boxing match and other events at Mack Park to recoup his losses, Foster threatened to cancel all of the Stars’ remaining league games if Blount didn’t pay the booking fee. Blount caved in, though Foster had nothing to do with arranging the events.

Late that September, Blount announced he was through. “I am not going any further,” he told assembled players. “I am tired of giving my money away.”

At a subsequent league meeting, he was formally stripped of the franchise and his position as NNL vice president. In 1931, the circuit collapsed, done in by Foster’s death and the Great Depression. The Stars, operating under a string of new owners, managed to survive until the very end.

No longer needing to juggle his baseball and gambling operations, Blount concentrated on the “office” he kept on Beacon Street, close to where Comerica Park now stands. The two-story frame dwelling actually was a warren of partitioned rooms offering illegal activities of all types. It was periodically raided by the vice squad, but payoffs and connections kept Blount out of jail and in business.

On Dec. 22, 1934, Blount went to his office to check on a pile of holiday foodstuffs he intended to distribute at Christmas. A short while later, a passerby heard moans coming from an open cellar door. Looking in, he discovered Blount laying at the bottom of the stairs.

Blount was rushed to Receiving Hospital, where he died of a cerebral hemorrhage without ever regaining consciousness. Some speculated that in searching for a light switch, he’d slipped and fallen.

But rumors circulated around Paradise Valley. There were bruises on Blount’s hands that looked like defense wounds. His fractured skull could as easily come from a club as a hard tumble down the stairs. It was possible he’d interrupted a robbery in progress or been targeted by one of his many enemies.

Police didn’t look too hard and in any case nobody was talking. Others quickly moved in to take over Blount’s action. Meanwhile, the man eulogized as a “baseball mogul” was laid to rest in Chicago.

It has been 90 years since Blount took a spill. Perhaps more on his curious death will one day surface. But as the old policy king himself might caution, don’t bet on it.

Richard Bak is the author of “When Lions Were Kings: The Detroit Lions and the Fabulous Fifties.”

This article originally appeared on Detroit Free Press: Detroit baseball baron lived large, died suspiciously