How the First Female Newscaster in Anchorage Kept the Town from Falling Apart During the Great Alaska Earthquake

Genie Chance was typing a letter to a friend when her 13-year-old son, Winston Jr., called Wins, appeared at her bedroom door. He needed a ride into downtown Anchorage to buy a copy of the Red Cross lifesaving manual for swim class the next day. The bookstore didn’t close until six o’clock, he told Genie. It was almost 5:30 p.m. They still had time.

Genie set her letter aside. “You’ve known for a week you had to have it,” she complained as they headed downstairs.

Genie’s 11-year-old son, Albert, was watching television in the living room. “We shouldn’t be gone more than five minutes,” Genie told him. Her husband, known to all as Big Winston, was still at work, and Genie’s youngest, 8-year-old Jan, was at the neighbor’s house. Genie pulled on her boots and parka and marshaled Wins into the car.

This wasn’t the first time that day, March 27, 1964—Good Friday—that Genie had been in town. She had set out for the city’s Public Safety Building about 7 a.m., as she did every morning, to sift through the police department’s overnight logs and booking slips, looking for news stories.

In her year and a half at KENI, one of Alaska’s top radio stations, Genie had transformed herself into an industrious roving reporter, covering crime, the courts, and city hall.

Sometimes she handed her copy to a male announcer to read, but often it was her own voice on the air. The 37-year-old, lithe with short, wavy blond hair, was said to be the first female newscaster in the state. In Anchorage, one of her coworkers wrote that everyone knew that “when something happens, their Genie will be right there telling them all about it.”

A working mother wasn’t supposed to be so driven. Many of the men at KENI dismissed her as stuck-up or dramatic. Genie did her best to defuse their discomfort. At the conclusion of a dogsled race a month earlier, she had signed off by thanking two male colleagues “for allowing this little gal to be a part of the broadcast crew.”

Snow was falling as Genie turned right on C Street. The city was quiet. Most people had already left work for the start of the Easter holiday weekend. The Salvation Army had just concluded its Good Friday worship. Volunteers at the Third Avenue Elks Lodge were coloring Easter eggs for their upcoming hunt.

It was 5:36 p.m.

The traffic light turned red as Genie and Wins approached the intersection of C Street and Ninth. The car started bucking as soon as Genie’s foot touched the brake. “Oh no,” she said. She assumed she’d blown a tire.

For a moment, they bounced violently without speaking a word. The shaking relented. Then came a forceful, heaving jolt. It knocked the traffic lights out. The electrical lines overhead started snapping like whips.

“What is it?” Wins asked.

“It must be a hard wind,” Genie said.

Across the street, a line of cars parked at the service station were bouncing into one another and separating again. They looked like a grotesque accordion opening and closing, Genie thought.

A man and two women came out of the liquor store to her left. They did not seem to be walking, exactly, but lurching. Then they fell down. When they got back on their feet, the man tried to protect the two women by hugging each one to the wall of the building they’d just stumbled out of. But then the building swayed away from the three of them—the building itself moved! Genie watched it bending left, then right. And as it did, she saw a crack open in the masonry over the man’s head and then close again.

Through the windshield, Genie watched the road roll away from the car. The pavement didn’t break apart; it was still solid. But it rolled, wavelike, as though some humpbacked shadow creature surged under its surface. As Genie’s car hopped more ferociously, leaving the ground and edging into the adjacent lane, she found the words to explain the chaos: “This is an earthquake!”

The onset of the quake unfolded like this for many people. The mayor of Anchorage stared at a raven outside his car window, watching it try to land on a thrashing streetlight for several seconds until, finally, the bird gave up and soared off. A woman watched her cast-iron pot of moose stew hop autonomously off the burner.

The earth yawned open and swallowed cars. One woman, watching hers vanish, said “good” out loud—she’d never liked that car. But then the ground thrust upward and ejected the vehicle again. Another woman found herself jumping over three-foot-wide crevasses as they split open in front of her, escaping to momentary safety again and again, cradling her baby the whole time. She noticed, fortuitously, that each new rupture was preceded by an audible warning that sounded as if “you dropped a dish and it didn’t break, just bounced,” she later explained.

The Great Alaska Earthquake, as it would come to be known, was the most powerful earthquake ever measured at the time and remains the second most powerful one to date. Its magnitude hit 9.2 on the Richter scale; its epicenter was 75 miles east of Anchorage and shallow, only about 15.5 miles underground.

The earthquake was so violent it reshaped the surface of the planet as it went. An uninhabited island southeast of Anchorage was knocked nearly 70 feet from its original position. Most of the landmass of North America momentarily jostled upward, in some places by as much as two inches. In Baton Rouge, Louisiana—4,000 miles away—a homeowner noticed his swimming pool jiggle.

The quake lasted nearly five minutes, long enough for some people to question whether it would ever stop.

Genie and Wins raced back home. Their stout, wood-shingled duplex was still standing, though the chimney had crumbled. As they pulled up, Jan and Albert shot out of the neighbor’s house. “You ought to see the inside of our house,” Albert shouted. “It’s a mess!”

Safe and reunited with each other, the Chance children understood that Genie would be leaving again to report on the situation. She hugged Albert and asked, “Are you sure you’re all right?”

“Don’t worry about me,” he said. “Go on and do your job.” Genie hugged him again and ran out to her car.

It was nearly six o’clock when Genie parked downtown and slammed the car door behind her. The true scope of the horror and destruction now hit her. On D Street, Genie stopped short in front of a slab of something in the snow. She stared at it, mesmerized and repulsed, but couldn’t place what it was. Finally a man explained: It was half a woman. He’d seen her get struck by the falling debris.

Genie, feeling nauseated, moved on quickly. On Fifth Avenue, the roof of the new J. C. Penney had slumped inward and massive swaths of the five-story exterior had collapsed, spilling plaster, lumber, and concrete up and down the block. It looked as though someone had stepped on the structure and its insides had slopped out. Volunteers were clearing debris off a flattened car with their bare hands. A 55-year-old woman was inside, her neck and arm broken. But she would survive.

Genie turned the corner onto Fourth Avenue and took in that impossible panorama. While one side of the city’s main thoroughfare seemed untouched by the earthquake, the other side of the street had simply dropped. For two whole blocks, everything was 11 or so feet lower than it had been, wedged in a ragged chasm that had ripped open under the street. Some of the buildings still appeared to be intact down there. Cars were lined up beside their parking meters.

The D&D Bar, the Sportsman’s Club, the Frisco Bar and Café, the pawnshop, the Anchorage Arcade—they were all now below ground level. In the immediate aftermath, men had emerged from the front doors of those sunken bars unharmed, many still clutching their drinks, and looked up like stunned miners.

After briefly returning home again to check on her family, Genie called in to the station on her car’s two-way radio while still parked in her driveway. She was prepared to make an initial report about the destruction she’d witnessed downtown. Though the station had been knocked off the air for a time, it was back on. “Go ahead, Genie,” the on-air announcer said.

Genie was ready, but how to proceed? She felt obligated to shield KENI’s listeners from the horror she’d witnessed. She intuited that if she described that body in the snow or the woman in the car, listeners would rush to assume it was their missing mother, wife, sister, or daughter. “A description of blood and gore could cause panic,” Genie would later explain. “We could not have panic.”

Speaking fast between sharp, quick breaths, Genie told those listening, “It has become obvious that the earthquake that struck Anchorage was a major one. A great deal of damage has been done throughout the city.” She advised people to check their supplies and keep their doors closed to retain the heat in their homes since the temperature would be in the high 20s. “But, uh, now another thing,” she continued. She was making it up as she went along, warning about as many hazards as she could remember from when she had dashed through downtown: Avoid tall buildings, which may still be susceptible to aftershocks; stay clear of power lines; stay put. And most of all, don’t panic. “Check on your neighbors. See if they have transistor radios. If they don’t, maybe they could move in with you and share one for the night. It seems like it’s going to be a long, cold night for Anchorage, so prepare to batten down the hatches, and stay tuned to KENI.”

Another tremor struck just as Genie finished. There would be 52 separate aftershocks over the next three days, 11 of which measured higher than 6.0. When the aftershock subsided, Genie drove back downtown. It was just after 6:40 p.m. Only one hour had passed since the quake.

“For the next 30 hours,” she would say later, “I talked constantly.”

When Genie arrived at the Public Safety Building, she told Anchorage’s fire chief, George Burns, and police chief, John Flanigan, that they were free to use her two-way radio to broadcast announcements. Instead, Chief Flanigan off-loaded that job to Genie. She would essentially be the city’s de facto public affairs officer, feeding the public information.

Genie was caught off guard. Shouldn’t authority figures such as the police chief and city manager be speaking to residents themselves? The citizens might trust those male voices more than hers.

Flanigan didn’t have time to discuss it. He was worried about people streaming into the downtown area to find loved ones, or just to gawk. Genie would need to tell the people of Anchorage that it wasn’t safe to travel around the city just then.

While colleagues reported the general earthquake news from the studio or a mobile unit, Genie relayed messages from law enforcement from inside her car parked just outside the Public Safety Building. “City police report that a high-voltage power line is down on Northern Lights Boulevard,” she said in one announcement. “State police report that there is a large crevasse in the Seward Highway about two miles south of the city limits of Anchorage. It is impassable at that point,” she relayed in another. In fact, “Both highways out of Anchorage are closed to through traffic … You are urged to stay home. Do not drive around to see the sights. Stay in your places and await further instructions.”

Soon, volunteers and city employees were rushing out of the Public Safety Building and appearing beside Genie’s car with more announcements to broadcast. She listed the locations of public shelters opening up for the displaced and started directing equipment and personnel around the city. “A first aid station is being set up at the old First Federal Savings and Loan Building,” she reported. “A doctor is needed there as soon as possible.” An assistant fire chief came to tell her, with some aggravation, that his men were seeing lit candles in people’s windows all over town. “This is a fire hazard,” Genie explained on the air. “If you are using candles, please light them only when it is necessary, and then use them with extreme care.”

Something else was happening that Friday night—people separated from family members were coming to Genie and asking her for help. They were desperate to know whether somebody they loved was safe or to let loved ones know that they were safe. They were eager to find one another, to shout across their fractured city in the dark. They hoped that Genie might amplify their voices with her own.

Genie had moved inside the building by this time, and among the first to come to her, around 9 p.m., was a couple.

“Mr. and Mrs. Fisher have lost their children,” Genie said, relaying their message over the air. “They said they will be waiting at the home of Charles Ball.” More people came. And as the telephone lines in the Public Safety Building reopened, many more called in. “Mel Fleeger,” Genie said, “we’ve received a call here at the fire station. Mel Fleeger who lives on 86th Avenue: The fire department dispatcher said it sounded like children calling, and they said please come home … Howard Forbes would like it to be known that he will be at Mike Whitmore’s … A message to Walter Hart: Lee Hart is fine … Jim Murphy and Bill Sarville at Point Hope: Your families are A-OK.”

In the ensuing years, after the rubble had been cleared and the city rebuilt, Genie went on to have a successful broadcasting career and serve in the Alaska legislature. She died in 1998 at the age of 71. But during those tense hours on the air that Good Friday night, Genie couldn’t help wondering how she wound up in the role of communicating instructions and hope to the public. As it turned out, she was the perfect person for the job.

While miraculously only nine people died in Anchorage—115 throughout the state—more than 1,400 properties were significantly damaged and over 900 homes destroyed. The electrical grid was down. Most phone lines were dead. People were cut off from each other.

One man who had fallen to the sandy bottom of a pit later said, “You just wonder, Where are you? You don’t know if anybody else is alive. Maybe you’re the last man.”

So it was reassuring to hear another voice on the radio, talking to you—especially a familiar voice.

“Genie Chance,” one listener explained, “was telling everyone, ‘You’re not alone.’ ”

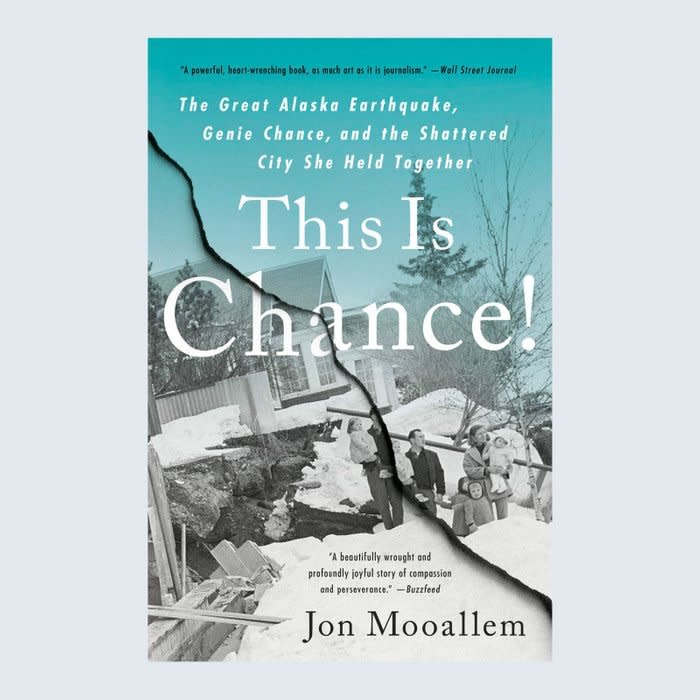

To read more about this story, purchase a copy of Jon Mooallem’s book, This Is Chance!: The Great Alaska Earthquake, Genie Chance, and the Shattered City She Held Together.

The post How the First Female Newscaster in Anchorage Kept the Town from Falling Apart During the Great Alaska Earthquake appeared first on Reader's Digest.