First coaches of brand-new Dolphins, Panthers, Marlins and Heat felt pain. Who were they?

The Miami Dolphins have a new head coach this season. So do the Florida Panthers. The Miami Marlins have a new manager. Meanwhile, the Miami Heat’s head coach has started his 15th season.

But who were the very first leaders of these teams when they started play decades ago?

In some cases, not who you might think. Don Shula was not the first coach of the Dolphins when the expansion team started play in 1966. Jack McKeon was not the first Marlins manager. And Pat Riley was still with the L.A. Lakers when the Heat was born.

Let’s take a look through the Miami Herald archives for a look at the first coaches when South Florida’s sports teams first came on the scene.

READ MORE: A look back at Dolfan Denny, the Dolphins’ original super fan

Miami Dolphins

First coach: George Wilson

By Greg Cote

Published Jan. 27, 2020

The players who formed the nucleus of the NFL’s single greatest team of all time were stunned to learn that their Dolphins head coach was prone to laziness and long, boozy lunches. He was a man who once stood before his team and, slouching, said, “Well, I’m hoping for a 7-7 season” - as his guys looked around at each other, dumbfounded.

This was before the arrival of Don Shula, we must hasten to mention.

The NFL itself anointed the 1972 Perfect Season Dolphins No. 1 among the best teams ever as part of its 100th season celebration that will culminate with the Chiefs-49ers Super Bowl, fittingly in Miami.

But how did a Miami franchise only born in 1966 get from nothing, from the comical dysfunction under first coach George Wilson, to being the greatest ever in such short order? It happened because of Shula, who arrived in 1970, but it started before him, during the expansion years.

It started with one man, a man long lost, a man so essential yet so egregiously forgotten in Dolphins history. His name was Joseph Henry Thomas. He left the windfall of talent that Shula spun into historic gold.

Joe Thomas was owner Joe Robbie’s first key executive hire, in 1965, as director of player personnel. Robbie called him “the keenest judge of player talent I have ever encountered.” The cantankerous, mercurial owner would fire Thomas after the ‘71 season, so he wasn’t around to enjoy the back-to-back Super Bowl wins he arguably had as much to do with as Shula or any one player.

“He was very overlooked,” says Larry Csonka, the Hall of Fame fullback. “Joe Thomas put together four-fifths of that ‘72 team. Shula’s biggest surprise was how much talent [he inherited].”

The treasure trove that awaited Shula included future Hall of Famers Bob Griese, Csonka, Larry Little, Nick Buoniconti and Paul Warfield, as well as future Dolphins greats Jim Kiick, Manny Fernandez, Dick Anderson, Bill Stanfill and Mercury Morris - among others.

By drafting or trades across a three- to four-year flurry, “Joe Thomas put all that together,” says Anderson.

The Dolphins, for the lack of recent glories to celebrate, have become a franchise that pays inordinate homage to its halcyon days, especially the 1972-73 pinnacle. Even now, nearly 50 years later, “What we have is earmarks from Joe Thomas,” as Morris puts it.

Thomas worked for the Vikings before coming to Miami and toiled with the Colts and 49ers afterward, finally ending his career back in Miami in 1979-82 as the Fins’ vice president assigned not to personnel but to the minutiae of player contracts.

He would die suddenly of a heart attack in his Coral Gables home in February 1983 at age 61, his career never duplicating the lightning he somehow lassoed for the pre-Shula Dolphins, or enjoying the credit for it.

One could argue Thomas should be in the Pro Football Hall of Fame in Canton, Ohio, as a contributor/executive if only for his work with the expansion Dolphins. One could argue even more forcefully that he should be on the Dolphins’ in-stadium Honor Roll.

Griese, the Dolphins’ first star, first future Hall of Famer to wear the uniform, recalls how he met Thomas ... although they didn’t meet, exactly.

This was Jan. 2, 1967, in the postgame locker room, after Griese had quarterbacked Purdue to its first Rose Bowl title, over Southern Cal. Players, still in uniform, were celebrating. Griese kept noticing a man in a suit watching him from afar. No, observing him.

A few months later the Dolphins made Griese their No. 1 draft pick, fourth overall, and the quarterback learned the man watching him celebrate that day had been Thomas.

“It was part of my study,” Thomas told him. “If I’m going to take a guy in the first round I want to see his attitude and approach after a game. Is he taking all of the credit or is he saying I could have played better?”

Those were different days. It was before the NFL/AFL merger. Dolphins road-trip rooming assignments were still segregated by race. A minimum rookie salary of $9,000 didn’t come along until 1970. Many of the expansion-era Dolphins had second jobs. Anderson sold insurance. [”He had this big Karl Malden car and a phone the size of a suitcase,” says Morris, laughing.]

Csonka first met Thomas during his senior year at Syracuse. In the winter.

“I said I hate the cold weather,” recalled Csonka. “He said, ‘You know the weather in Miami?’ “

He was grinning when he said it.

A few months later Csonka, the bulwark fullback, was Miami’s No. 1 pick in the 1968 draft.

“Joe wanted to know about you,” Csonka says. “You can look at the tape, but Joe studied it deeper than that. He had spoken with some of my high school coaches, my junior high principal. Wanted to know my grade-point average and attention span. If I could grasp things. Sometimes he’d get so revved up [talking football] that he almost stuttered sometimes.”

After the ‘68 season, in the throes of a terrible concussion, Csonka wondered if he could go on with this fledgling career. Miami’s offensive line was that bad, or, as Zonk put it, “Not necessarily an All-Pro entity.”

He was at the old Eglin Buick dealership in Miami one day having work done on a car.

“I open a door and run into a wall,” says Csonka. “The wall was Larry Little.”

Little, a Miami guy from Booker T. Washington High, was a backup guard for the San Diego Chargers at the time.

Csonka left the dealer in a rental car, headed straight to 330 Biscayne Blvd. and up to Thomas’ third-floor office.

“I said, ‘Joe have you ever heard of Larry Little? I can hide behind him!’ “

Of course Thomas had. He tried to get Little as a free agent only to learn he had signed with the Chargers one day earlier. So Thomas worked a deal. San Diego got a little-known and short-lived defensive back named Mack Lamb. Miami got a future Hall of Fame guard who would pave Csonka’s path for years, in one of the most lopsided trades in NFL history.

Back in those few years, Midas wanted Thomas to touch him.

The expansion Dolphins were losing big but stockpiling enormous talent all over the field.

If only the coaching staff knew that, or knew what to do with it.

To be fair, Wilson, who would die at age 64 in 1978, had his day. As a player he had been a four-time champion as a two-way end for the Bears in the 1940s. His Lions won the 1957 NFL championship in his first year as a head coach.

But the last stop on his career, Miami, found him aging, tired and coasting toward retirement.

“I was so much better prepared in college [at Colorado] than when I came to the Dolphins,” says Anderson, the great safety. “As a rookie I thought to myself, ‘This is professional football?’ “

Little recalls one especially hot day, “And George says, ‘Oh what the hell. Go jump in the pool. No practice today!’ “

“We’d go swimming like it was summer camp!” says Morris.

Once, with the coaches ostensibly behind closed doors in a staff meeting or studying film, a player walked in to find Wilson and his buddies playing cards. Gin was the preferred game. With liquor, it was Manhattans and martinis.

The drinking was an open secret, betrayed with a whiff of breath.

Wilson and his crony-filled staff would break for lunch “for two or three hours,” recalls Anderson - lunch being a relative term there.

“They were coming and having three or four drinks to have practice,” Anderson says.

Griese recalls Wilson and his coaches making a routine of “lunching,” between practice sessions, at long-defunct Johnny Raffa’s Restaurant & Lobo Lounge on Biscayne Boulevard.

“They’d have a couple of martinis or whatever,” says Griese. “This was George Wilson at the end of his career. We had an expansion team. We weren’t going to win.”

Well, they weren’t going to win like that.

Something had to happen. And something did.

Donald Francis Shula happened.

Miami Marlins

First manager: Rene Lachemann

By S.L. Price

Published Oct. 24, 1992

Rene Lachemann took over Friday as the first manager of the Marlins. He tugged on an aqua cap, held up his jersey for the cameras. He announced the hiring of his brother Marcel as pitching coach. It was all very anticlimactic.

Then he opened the floor to questions.

Then it became clear that running a team in South Florida will be different than anywhere else.

The fact that he has had some embarrassing moments as a third-base coach? Not an issue. Yes, Lachemann, 47, was asked about his three-year contract guaranteeing close to $1 million, his brother, his managing style. But over and over, it was his cultural credentials that received the most intense scrutiny.

A man asked, Will any of your coaches be Latin? Another said, Will you go after any Latin free agents? Then this: Do you want Jose Canseco here? Will you discriminate against Latins? Another reporter began, Latins are different, they want to win quickly, so . . .

“I think Latins are the same as anybody,” Lachemann said. “They want to win just like anybody else.” Only he wasn’t speaking English.

Perdoneme, he said. Pero mi espanol es muy malo. Translation: Sorry, but my Spanish is very bad. But in his first test in a place where pressure comes wrapped in two languages, Lachemann still managed to say all the right things - bilingually.

His four coaching vacancies? “I’m looking at people who are qualified, who can do the job,” Lachemann said. “I think a Latin coach can do the job. But it depends on their availability. I’m not going to bring in friends, people who will play golf with you. I’ve got to bring in people who can work.

“I definitely have a list. Latin Americans coaches are on that list. I’ve had phone calls now that run up and down from Venezuela, Puerto Rico to San Pedro - in California, not in San Pedro de Macoris. I know we’ll be getting them all.”

Hispanic players? “What we’re looking at is bringing in the best players in we can get,” Lachemann said. “Venezuelan All-Stars, Puerto Rican All-Stars -- I don’t care. I just want to get the best.”

Lachemann talked about his experience managing a team composed entirely of black and Hispanic players at Triple-A San Jose in 1977 and ‘78. He spoke of his experience managing six years in the Latin winter leagues -- from Puerto Rico to Venezuela to Mexico. He was asked about his six years with Canseco in Oakland.

“Me gusta mucho,” Lachemann said. I like him very much. But I can’t talk about him because . . . “como se dice -- Tampering?”

The line got a big laugh -- and clearly was the kind of thing Marlins management hoped for when they decided on Lachemann last week. One reporter opened her questioning of Marlins General Manager Dave Dombrowski by saying, “He speaks Spanish. Very impressive.” Dombrowski looked delighted.

But while a factor, Lachemann’s ability to entertain en espanol wasn’t the main reason Dombrowski and Marlins President Carl Barger chose Lachemann over 61-year-old Pirates coach Bill Virdon.

“I see him as a manager who can take us from one level to the next,” Dombrowski said. “You look at Bill, his age. Could I imagine him managing in 10 years here? I don’t think so. But Lache is 47. Can I envision him being here in 10 years? Yes, I can.”

Such long-range thinking for an expansion manager is unheard of in baseball - as Lachemann well knows. He compiled a 207-274 record with Seattle and Milwaukee in 1981-84, and was fired twice in two seasons. He hasn’t managed since, serving as an assistant coach in Boston for two years and then in Oakland for the past six seasons.

But despite the fact that first-year expansion managers don’t last too long, Lachemann isn’t interested in losing and leaving.

“I’m not looking to turn it over to anybody else,” he said. “I’m not here to be the person to build it up and then see-you-later. But I know the territory a manager walks in. Sooner or later you’d better win or you’re gone. But I’m not scared of that.”

Dombrowski said he never consulted with Lachemann’s former employers in Seattle and Milwaukee. Instead, he relied heavily on the evaluation of A’s manager and close friend Tony La Russa and A’s General Manager Sandy Alderson.

“I asked them both why Lache was more prepared now than before, and they said: ‘No comparison,’ “ Dombrowski said. “In the past, some said he was too close to his players. He’s learned from that.

“I asked Sandy, ‘If you lost Tony La Russa as manager, would he be someone you’d consider?’ And Sandy said, ‘Most definitely.’ And the next day, he called back and said, ‘When I think about Marcel being pitching coach, I don’t know where you’d get a better combination. You can’t get a better manager than Lache and when you put the two together you can’t beat it.’ “

That, of course, was the day’s most charming aspect. Marcel, 51, has spent the past 11 seasons with the California Angels, in summers meeting his brother only on the other side of the field. The two haven’t worked together since they were teammates on the Iowa Oaks in 1972. This should please their 92- year-old father, William.

“He always used to worry when we played each other,” Marcel said. “And my mother, when she was alive and he was with Milwaukee and I was with California - she’d wear two hats to watch the game. I think this is going to make it easier for him.”

For now, though, Lachemann is already thinking ahead to next month’s expansion draft, to piecing together his staff from a list of 120 names, to planning for spring training and the months of tension ahead. But if Opening Days mean anything - and they usually don’t - then Lachemann has won over at least one member of a difficult audience.

“You were a star today,” said Barger as he shook Lachemann’s hand. “An absolute star.”

Miami Heat

First coach: Ron Rothstein

By Dave Hyde

Published July 12, 1988

Ron Rothstein, the Miami Heat’s first coach, is no stranger to expansion teams and the uncomely trials they bring. Fact is, in the fall of 1966, Rothstein’s first head coaching job was with another expansion team in another league.

he team was Eastchester (N.Y.) High School and the league was the Southern Westchester Interscholastic Athletic Conference. The job description, however, was eerily similar to today’s with the Heat: Kick-start a program, perhaps suffer early, but come out a winner.

To be sure, Rothstein succeeded completely. Eastchester High never finished lower than third in the eight-team league over Rothstein’s final 10 years until he left for the pros in 1983. He was “in his own orbit as a coach” and “loved by his players,” remembers Eastchester Athletic Director Dominic Cecere.

But in 1966? The expansion year? “It wasn’t what you’d call a high point,” said Cecere, Eastchester’s junior varsity coach and Rothstein’s assistant at the time.

0-36.

That was the record. The situation was painfully similar to today’s reality. He had to build excitement in a town with no history of basketball. He had to build a team from an undermanned lineup. Eastchester was 12 miles north of New York City, had an enrollment of 400 and a frontline in 1966 that measured 6-0, 6-0 and 5-11.

And, if the program’s foundation was weak, so was the gym’s. It was built in 1927, had a dead spot at midcourt and two feet between the basket and the wall. It had yellow, suspended lighting and smelled, like most old gyms, like canned sweat.

But, most of all, that first year the gym had an 0-36 team.

“He was very patient, very professional and there was only one time that he really got frustrated,” Cecere remembers. “It was the last game of the year against Harrison High. We were up by 12 with about five minutes left and I said to him, ‘Ronnie, we finally won one.’ He said, ‘No, no, don’t say that.’

“Well, at that time I had to go in the locker room and make sure (the junior varsity team) was ready. When I came out there were 11 seconds left and we were only winning by one.

“They had a kid that went the length of the court and threw up an underhand layup from the foul line and banked it in. A real Hail Mary. Well, as you might expect, Ron was dejected. He said something like, ‘I don’t know if I was meant to do this.’

“It’s the only time I remember Ron ever saying anything like that.”

But, as Cecere remembers, Rothstein took his wife for vacation in Puerto Rico after the season and “came back talking basketball again.”

Nothing unusual there. He was always talking basketball, his peers at that time remember. As a point guard at the University of Rhode Island from 1960 to 1964, Rothstein “was 5-8 physical specimen who played 6-10. He had a mind for the game no one else on the team had.”

He also had a heart for the game like no one else.

“We were married right around the same time so we would take our wives out together to celebrate our anniversaries,” Cecere said. “One time he had us take them to (Madison Square Garden) for a basketball game. The guy loves the game.”

While at Eastchester, Rothstein made friends one summer with some young, bright coaches named Hubie Brown and Mike Fratello at the Five Star Basketball Camp in New York. He was soon moonlighting as a pro scout for Brown and would eventually leave Eastchester to become Brown’s assistant at New York and Fratello’s at Atlanta before moving to Detroit.

But if, as in life, coaches’ first years set a noteworthy pattern, here’s some of the things Heat players can expect:

- Dressing up. “The kids had to dress up the day of a game - wear a shirt, tie, sports jacket, the whole bit,” Cecere said. “He really insisted they looked first class. And all uniforms had to be kept on a hanger in the locker.”

- Fiery talks. “His halftime speeches were always interesting,” said Jerry Hanchrow, an assistant under Rothstein and now Eastchester’s basketball coach. “He is a very dynamic person and always tried to get the kids fired up. Sometimes he got me more fired up than them.” Said Cecere: “At his practices, I usually closed the door. He would flare up when kids didn’t give effort.”

- Organization. “He was super-organized,” Cecere said. “Every practice was planned down to the second, which at the time was considered revolutionary. He would go to clinics out in Detroit or in New York or wherever and come back with loads of ideas.”

- Defense, defense, defense. “At Eastchester, believe me, he won with his defense,” Scott said. “With a frontline of 6-0 and 6-1 he couldn’t power the ball inside. But he had constant pressure defense. He became known for that all over Westchester County.”

And, of course, all over the NBA as well.

“I think Ron’s one of the top two or three defensive minds in the NBA,” said Heat expansion draftee Scott Hastings, a 6-10 center who played with the Atlanta Hawks for two seasons when Rothstein was an assistant there.

“We may not have as much talent as other teams, but there are two things we can do every night and that’s play hard and play good defense. I know we’ll do both of those under Ron.” Whatever next season brings, it is, as Cecere says, “a Cinderella story. When you think of where he started . . .”

At 0-36? Do they every discuss that season?

“No, we don’t talk about it,” he said. “We only joke about it.”

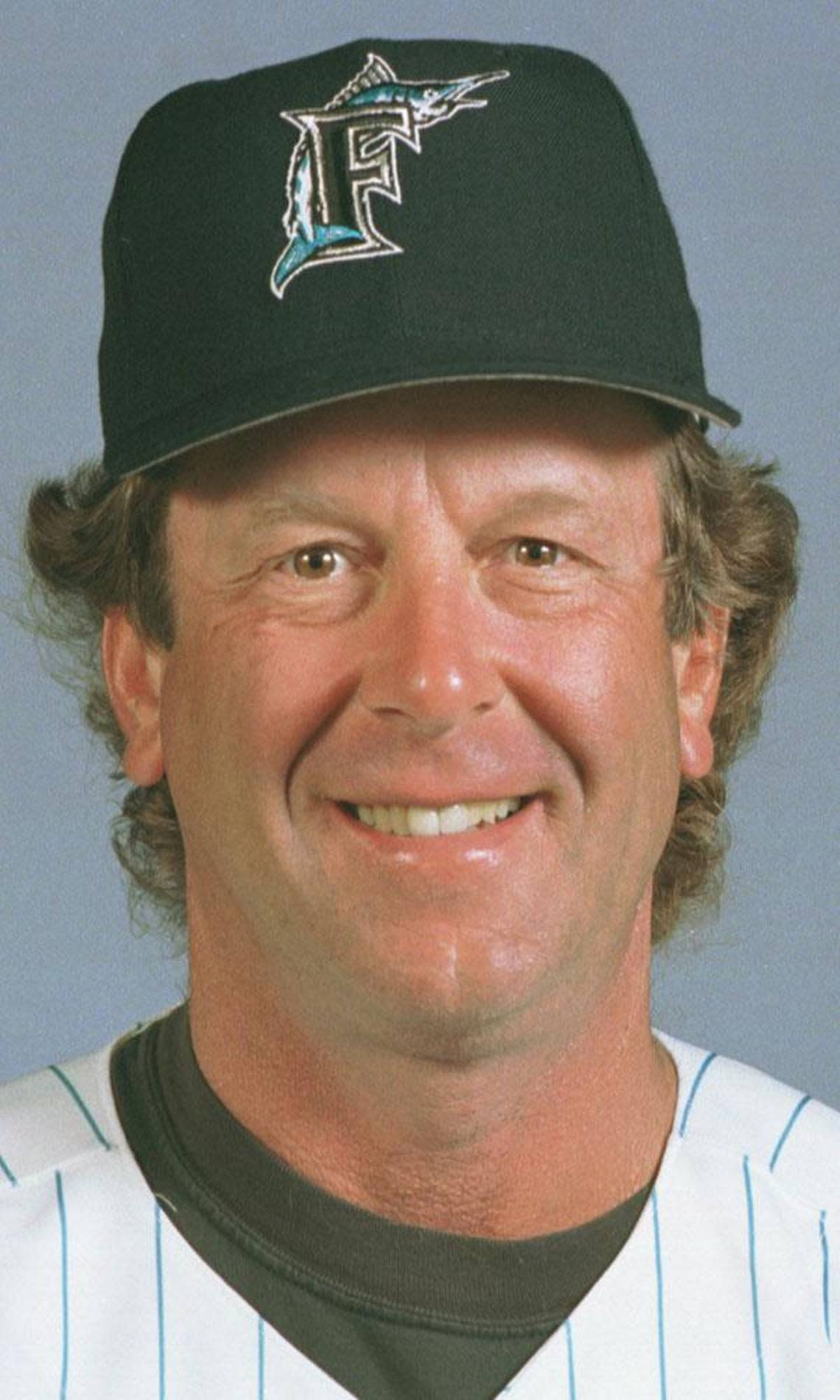

Florida Panthers

First coach: Roger Neilson

By S.L. Price

Published June 3, 1993

There was a river below, gray water rushing. Roger Neilson stared. He had some sort of strap around his waist, he stood on the edge of a cliff 200 feet up, and what once was a good idea suddenly had its . . . drawbacks.

This was five months ago. He is 58 years old.

“But all the guys I was with said they wanted to go, so I said, ‘Mmmm,’ “ Neilson said. “ ‘If I can do the Rangers, I can do this.’ “

So Neilson jumped. And though his beloved dog Mike had died and he’d just been fired and now he was in New Zealand, as

far from hockey as possible and trying to forget -- and though, seconds later, he certainly looked like a man at the end of his rope - this wasn’t an act of desperation.

Neilson had been through all of it before. Dog dead, job gone, future unclear. He knew something would turn up. That is how it works for the hockey lifer. Something always turns up.

On Wednesday, the Florida Panthers officially named Neilson the expansion franchise’s first coach, signing him to a three- year contract with an option for a fourth. Someone asked if he considered it a risk. “Hey, I’ve been with seven different teams,” Neilson said. “So risk is not even a consideration.”

Not for the Panthers. With his teaching background, history of making bad teams better, willingness to innovate and emphasis on defense, Neilson was a choice pick for a team that doesn’t exist yet. He is blunt, and he can be entertaining. A decade ago with Vancouver, he shook a white towel in mock surrender; Canucks fans then waved thousands of them like banners through the team’s stunning run into the Stanley Cup Finals.

He is, like President Bill Torrey and General Manager Bobby Clarke, an anomaly in the new age of Sun Belt hockey. With even purists preaching that goonism must end for the NHL to become a prime-time sell, Neilson is an unrepentant throwback.

“I don’t think people want to see brawls, but people like a good scrap now and then,” Neilson said.

“I don’t think that hurts anything. The way it’s set up now, each team has two or three guys and there’s the odd fight; everybody stands back and hardly anyone gets hurt. . . . If you don’t want to fight in the NHL, you don’t have to. But every time I’ve seen a fight in the NHL, people stand up and cheer. It livens up a dull game sometimes.”

Don’t get the wrong idea. He has been coaching hockey since 1966, but Neilson is no dinosaur. He was the first NHL coach to use video as a teaching tool, and his coaching clinics have become mandatory for many NHL assistants. He coached the New York Rangers to two Patrick Division titles, leading them in 1991-92 to their best regular-season finish ever (50-25-5).

And yet, Neilson’s tenure in New York ended in acrimony, a bitter feud with superstar Mark Messier, and the club’s quest for its first Stanley Cup since 1940.

“It’s different in New York,” Neilson said. “People don’t come up to you and say, ‘I’m hoping you have a great year.’ All they say is, ‘You’ve got to win the Stanley Cup.’ A guy says, ‘I’ve been waiting 50 years!’ and he’s only 28 years old. I’ve never been around anything like that. It’ll be a relief to get away from that. That was crazy.”

More unsettling, though, was the way it ended, in a power struggle with Messier that he had no chance of winning. After a blissful co-existence the year before, last season Messier grew impatient with Neilson’s physical, defense-oriented approach, Neilson accused Messier of relinquishing his leadership role, and the season unraveled.

On Jan. 4, Neilson was fired, just one more coach who violated the cardinal rule of modern sports: Get along with your stars. “I just don’t think a player can ever move up to another level when he’s still a player,” Neilson said. “The player has to stay at the player level.”

Of course, that isn’t the way in the NBA or major-league baseball anymore, and it won’t be in the NHL for long. But with this team, Neilson shouldn’t have to worry. There won’t be any superstar Panthers any time soon.

One thing is sure: Neilson will give the Panthers all of his time. He is not married. For the past 14 years, he took his mixed-breed Husky Labrador, Mike, everywhere he went. For the past four years, Mike lived in a doghouse at the Rangers’ practice facility in Rye, N.Y.

“When you’re single, you’ve got to talk to somebody,” Neilson said.

But three days after Neilson was fired by the Rangers, Mike died of old age. Neilson loaded him up in his car, drove back to his home on Chemong Lake in Ontario and buried him there. “After he was gone, I’d say something and he wasn’t there,” Neilson said. “A dog’s a good listener. You miss him.”

Neilson grins as he says all this, because he knows it is odd. But there it is, as much a part of him as the quiet wariness he carries like baggage. Someone told him Wednesday that he looked nervous, and Neilson shrugged, “Naw, I always look this way.”

It is the look of a lifer, with a face formed by knowing that nothing lasts forever -- certainly not a job. Coaching is a dog’s life, and no one knows this better than he.