Finding Myself in the Beautiful Queerness of Nature

"Hearst Magazines and Yahoo may earn commission or revenue on some items through these links."

In 2021, I became aware of two truths. The first was that I was transfixed by biology; I wanted to learn everything about the world around me. The second was that my biology was not my own.

I was a few years into my role as editor-in-chief of Atmos, a nature magazine I co-founded, and I was newly out as a trans woman. There was a voice in my head that told me those two identities could not coexist, that they were at odds with each other: the result of a lifetime’s worth of hearing bigoted rhetoric about trans people—and queer people at large—being unnatural. This is often rooted in bioessentialism: the idea that gender is determined by one’s birth sex, an immutable dictate by nature. But for me, transitioning was about accepting my nature after a lifetime of wrestling with it: the person I had always felt inside.

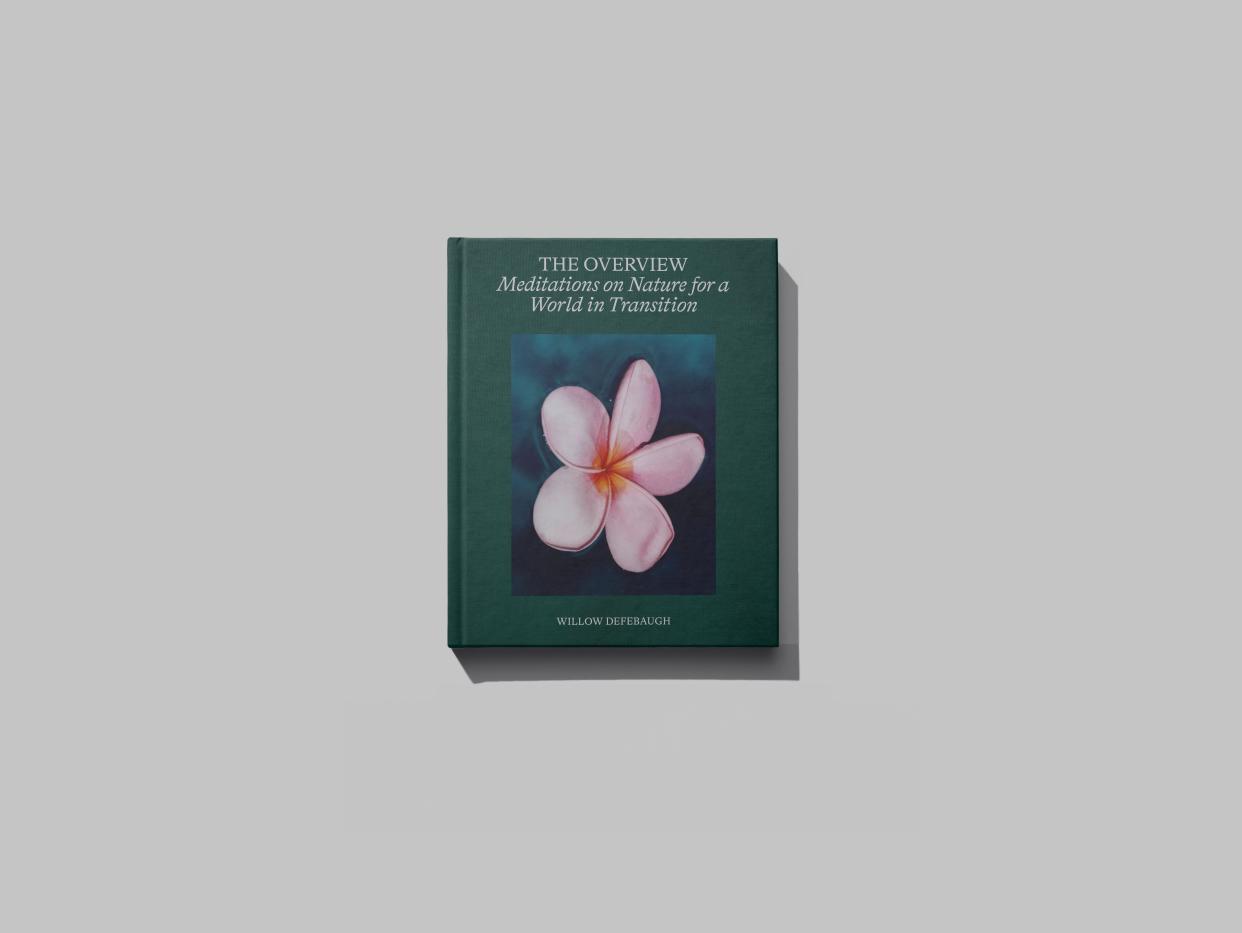

In doing so, I made my biology my own. Through hormone replacement therapy (HRT), I watched over years as my body bloomed and slowly began to take a shape that more closely aligned with my internal knowing. While navigating such immense change, I turned to nature for grounding and wisdom. I started writing a weekly newsletter in which I would turn to a different species or earthly phenomenon for some human insight I could hold onto. Now, one hundred of those essays are being released as a hardbound book, The Overview: Meditations on Nature for a World in Transition.

The Overview: Meditations on Nature for a World in Transition

Atmos

$60.00

Included among the organisms I attempted to wax poetic on were those that challenge our binary notions of sexuality and gender. The burgeoning field of queer ecology seeks to disprove the idea that LGTBQ people could ever be unnatural by breaking down human exceptionalism and highlighting the ways in which nature itself is inarguably queer.

As Lee Pivnik, founder of the Institute of Queer Ecology, once told Atmos: “The project of queer ecology is to free other species from the script of the history in which they’ve been written about mainly in a white/European, straight male, context, and kind of giving everything from other species to the people that are working in this practice—the agency to tell stories themselves.”

The most obvious example of this is that the animal kingdom teems with homosexual behavior; such behaviour has been observed in over 1,500 species and groups including primates, dolphins, lions, giraffes, starfish, bats, and snakes. And it’s about more than just sex: it can also involve cuddling and courtship through songs and signals. Some non-human animals including penguins have even been known to mate in monogamous homosexual relationships, such as Elmer and Lima, two male penguins who became fathers at New York’s Rosamund Gifford Zoo in 2022..

Transexuality swells in nature as well. Clownfish—all of which are born male—live in schools with one dominant female. When she dies, the dominant males turn female so that the school can reproduce and create new offspring. Hawkfish are even more fluid, changing back and forth between male and female. And then there are male cuttlefish, who adopt the coloring of females to appear non-threatening to other males during courtship. I found comfort in learning about these aquatic creatures—in the knowledge that my own fluidity was reflected under the sea.

There are more colorful displays of gender nonconformity in nature, too. Males and females of a number of animal species take on distinct appearances from one another, varying in size and coloration. Gynandromorphism is a phenomenon that occurs when an organism displays characteristics of both. In some birds and butterflies, that can even look like coloration that’s split right down the middle, with one half of their body appearing male and the other female. Written on their wings is a reminder that some might consider a mutation is no less beautiful.

The list goes on, with simultaneously hermaphroditic slugs that can get each other pregnant and snakes that reproduce asexually. And it’s not only the animal kingdom: plants and fungi display vibrant sexual diversity as well. There are cosexual trees that possess both male and female reproductive parts in the same flowers, plants that change sex during their lifecycle, and certain species of fungi that have over 23,000 variations of what we would consider sex. Fungi are known for decomposing matter; for me, they broke down our binary ideas about identity.

So where did these binary notions of biological sex and gender come from? In her book Bitch: On the Female of the Species, biologist Lucy Cooke traces this back to French embryologist Alfred Jost’s Organizational Concept, which attempted to divide mammalian sex into oppressive binary and hierarchical categories, with male being the dominant and female the passive default.

Cooke disrupts this theory by highlighting examples from the natural world that confront our cultural considerations of what it means to be female. This includes female spotted hyenas with clitorises that become erect and are larger than their male counterparts’ penises; female moles with gonads and spider monkeys with phalluses; female South American bats and blue whales that are larger and more dominant than the males; and female frogs with XY chromosomes.

And so I have come to understand myself as part of a sprawling tree of organisms that expands, not shrinks, our ideas of what it means to be a woman. To say that I am abnormal is to reinforce human exceptionalism—the idea that our species is somehow exempt from the natural world, the very same thinking that has allowed the climate and ecological crises to unfold as it has.

Biology is often weaponized against queer and trans people, but how can we ever be unnatural when all of the facets that give shape to our sprawling identities can be found in other species? Now more than ever, it’s imperative we question narratives around what is natural, because bigoted beliefs can become law. My book arrives amidst attacks on trans rights and access to life-saving healthcare being at an all-time high. As of the end of last year, the ACLU had tracked 510 anti-LGBTQ bills in the United States. There are expected to be even more in 2024.

As I write in The Overview: “While conservatives cling to bioessentialism, nature sings of beautiful biodiversity. For too long, Western ideas about gender and sexuality have been imposed upon the human and nonhuman worlds. Any arguments which claim that LGBTQ people are unnatural stem from the same thinking that separated humans from the rest of nature in the first place. Humans are queer just like nature is queer, because we are nature.”

You Might Also Like