US cities’ mansion taxes see mixed results

When Los Angeles voters approved an extra tax last year on home sales over $5 million, officials projected annual revenue of $700 million to help alleviate the city's rampant homelessness crisis.

But a year in, LA's “mansion tax” has fallen far short of expectations — generating barely a quarter of the promised revenue — and has arguably put a chill on high-end home sales as wealthy homeowners stay put rather than pay the six-figure tax bill.

"Given the high-interest rate environment we find ourselves in and now this exorbitant tax on top, if you don't need to sell, why would you?" Jon Grauman, founder of Grauman Rosenfeld, a luxury real estate firm in LA, told Yahoo Finance.

All the while, homelessness has worsened.

There’s now a movement to repeal LA's mansion tax in November, and similar measures around the country are meeting mixed results. Chicago voters recently rejected their mansion tax, while Berkeley has found some success in the policy.

A handful of municipalities — spread across California, New York, Illinois, Connecticut, Maryland, and New Mexico — have implemented some form of a mansion tax. But what once seemed a promising populist answer to worsening home affordability could now be compounding the problem.

Read more: Mansion taxes are on the ballot. How do they work?

Los Angeles sellers pull back from high taxes

The city’s mansion tax, known as the United to House LA (ULA) measure, imposes a 4% real estate transfer tax on properties selling for between $5 million and $10 million and 5.5% on properties selling for over $10 million. That means home sellers pay a one-time tax of $200,000 on a $5 million property sale.

The ballot measure passed with 58% voter approval last April. But since its implementation, transactions for homes in this price range cratered. Only 230 homes over $5 million have sold in Los Angeles since ULA was enacted, a 60% decline from the 570 homes sold in the previous 12-month period, data from Redfin shows.

The demand for housing remains — it’s the sellers’ unwillingness to list their homes that caused the decline. The number of home listings over $5 million declined 27% in the past year to 800 properties.

“Most people just think that it's incredibly unfair and inequitable,” Grauman said. “I sit down with homeowners almost every day in their living rooms and walk them through this and illustrate for them the impact that this is going to have on their bottom line.”

“[City officials] have created a massive disincentive for homeowners to sell,” Grauman added.

To be clear, even someone selling for less than what they paid would be liable for the tax.

Eric Sussman, adjunct professor at the UCLA Anderson School of Management, questions how taxing more would reduce housing affordability when similar policies haven't worked in the past.

"It's a terrible rule. It was just another nail in the coffin with the higher rates,” said Sussman, noting that the city previously funded more than $1 billion to reduce homelessness.

Both experts also questioned setting the threshold at $5 million, arguing that these homes are only sometimes a luxury in Los Angeles and definitely not mansions.

"It's sort of weird and crazy to think that a $5 million home is not ultra-luxury. It isn't," Sussman said. "In Los Angeles, a million dollars gets a shoebox."

Current listings show that nearly 1 in 5 listed homes is priced over $5 million. The median home sale price is around $1 million for 1,330 square feet, according to Realtor.com.

Read more: Why are home prices so high?

Berkeley declares rare win on homelessness

Cities typically set mansion tax thresholds above their median home prices in order to exempt average households. Berkeley, Calif., passed a progressive mansion tax in 2018 that adjusts for market fluctuation annually. It tracks and taxes the top third of the highest-dollar transactions.

Berkeley has seen signs of its initiatives working. The city's homeless population dropped 5% for the first time in 2022, according to its latest official count. Mansion tax revenues provide an average of $10 million in funding annually, supporting services like permanent housing, improved street conditions and hygiene, and emergency shelters.

One major drawback is that the housing market is volatile, and the revenue stream could dry up during a bad year. But Andy Boardman, a local policy analyst at the Institute on Taxation and Economic Policy, remains optimistic.

"Mansion tax can be a way to achieve a better overall balance when the economy is growing, inequality is growing, and folks at the top are doing really well, and you are able to capture that," Boardman told Yahoo Finance.

Sussman countered that taxing 33% of home sales is “doing a disfavor to the state.” Californians already pay the highest state taxes in the country, driving some people and businesses to leave.

“We're still running a deficit,” Sussman said. “We can keep taxing, taxing, taxing, thinking that's going to get us out of this. No, it's not.”

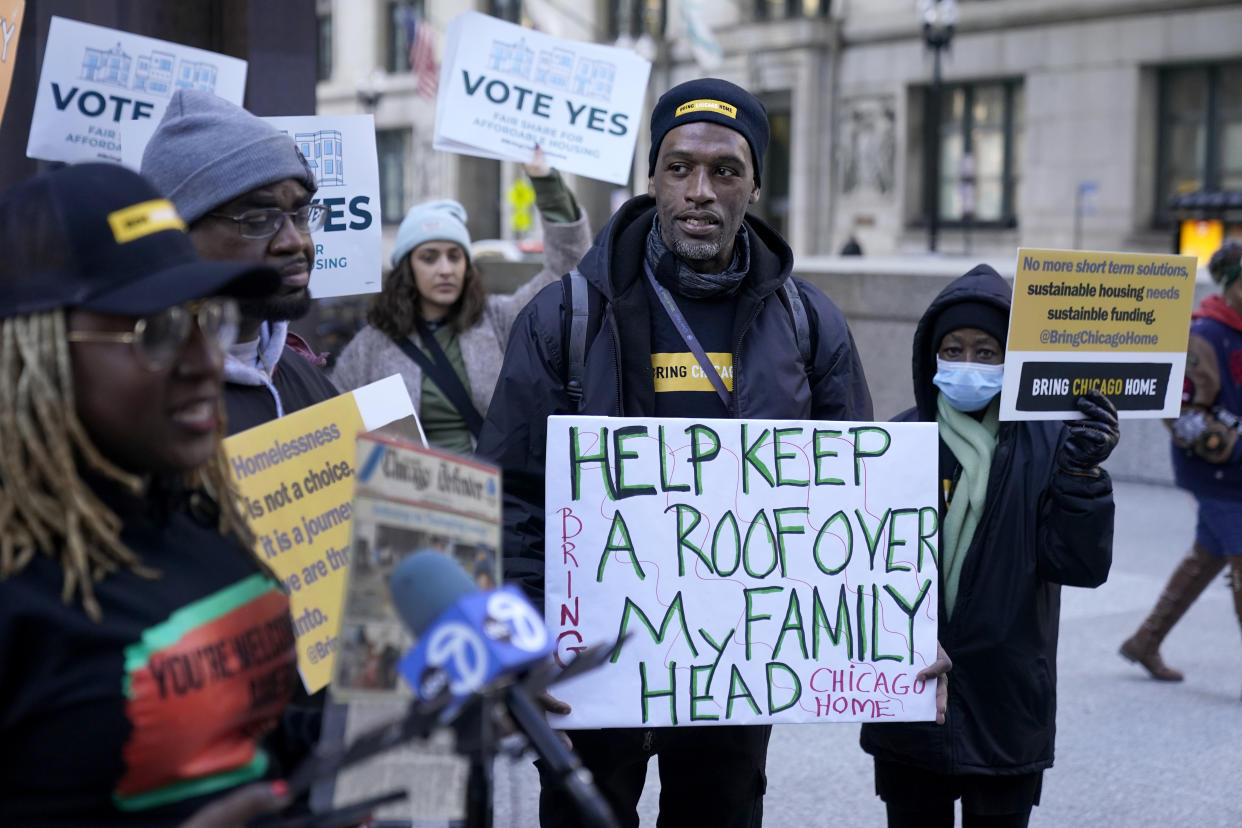

Chicagoans reject the referendum

Fourteen US cities enacted the mansion tax starting in 2014, an explosive trend compared to six cities over the previous 40 years. Multiple communities in Massachusetts, including Boston, are eyeing similar adoption.

Yet just last month, about 53% of voters in Chicago rejected the city’s proposed 2% real estate transfer tax on properties over $1 million and 3% on properties over $1.5 million.

Many voters feared that a new tax would have a negative ripple effect — the extra costs would intensify commercial real estate’s financial stress, forcing the government to pass off revenue burdens on residents by raising property taxes without solving the city's affordability problem for the middle class.

“Our concerns about growth, housing stock, and our dwindling supply of affordable housing — which, in my ward, is largely built by private developers — resonated with voters," Bennett Lawson, a Chicago councilman, told Axios.

Rebecca Chen is a reporter for Yahoo Finance and previously worked as an investment tax certified public accountant (CPA).

Read the latest financial and business news from Yahoo Finance