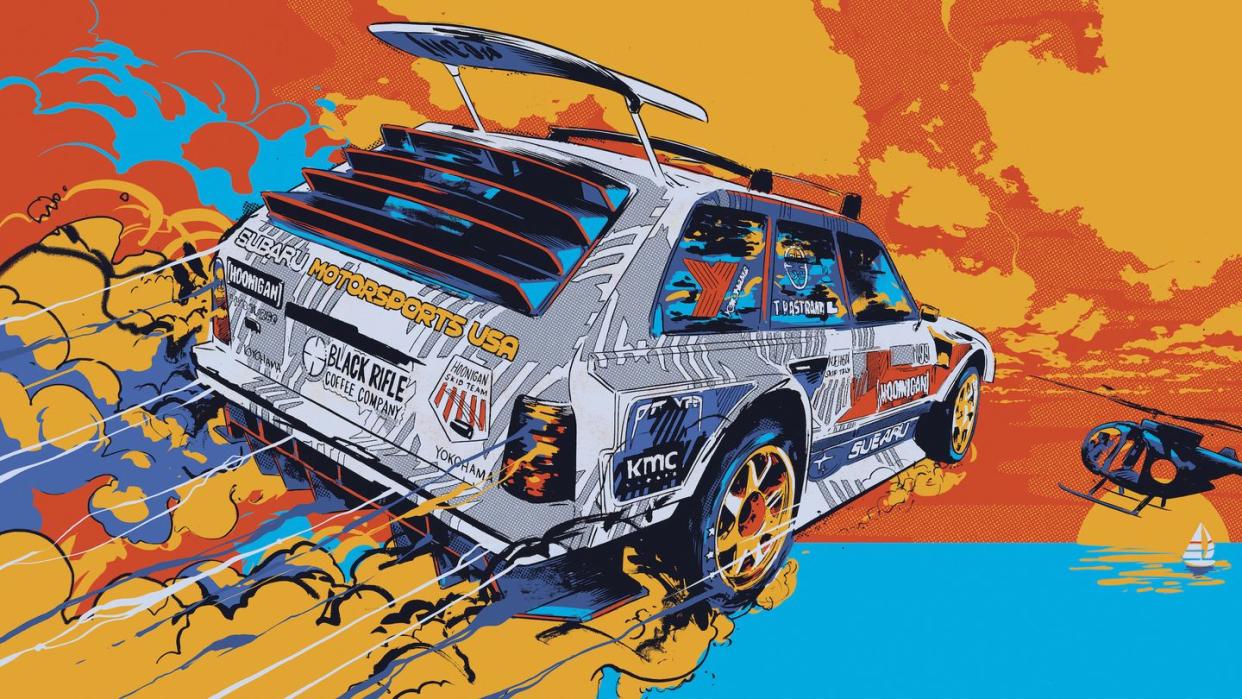

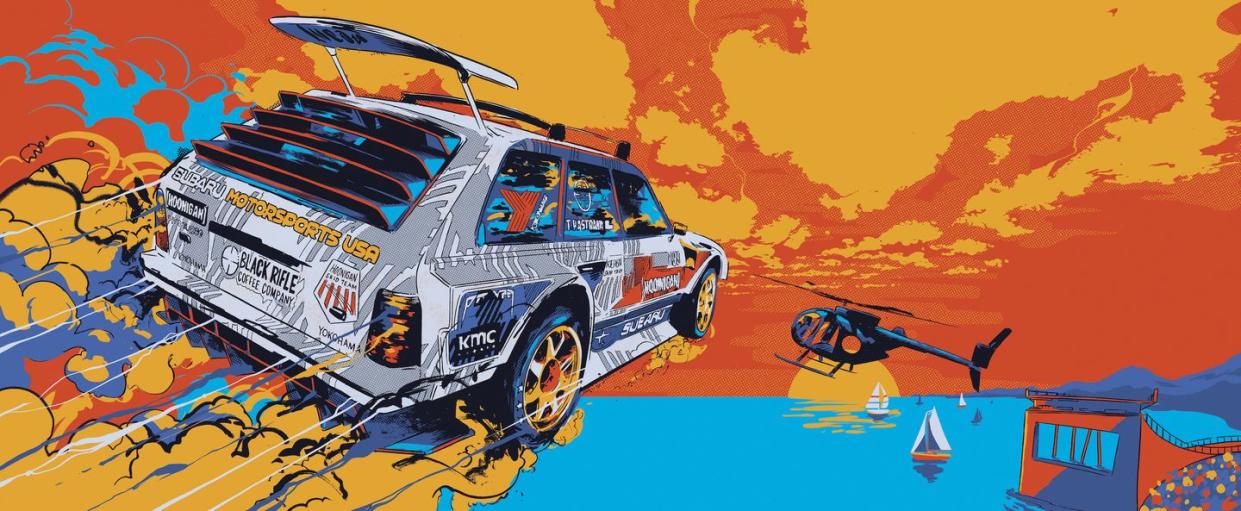

Let Travis Pastrana Tell You What It's Like to Jump a Car

Travis Pastrana has spent a preposterous amount of time in midair: as a kid, jumping a BMX bike into a sand pile; as a teen Moto X Freestyle phenom, nailing high-flying Superman seat grabs; as an adult, sending a Subaru rally car 269 feet across Long Beach Harbor. He’s tossed himself out of a Cessna without a parachute. He landed a groundbreaking double backflip at the X Games in 2006 and stuck a barge-to-barge backflip on London’s River Thames with such ease that you’d swear it was a matter of evolutionary adaptation instead of mere skill.

This story originally appeared in Volume 21 of Road & Track.

Exactly how Pastrana achieves human flight—minus wings—sits at the nexus of applied physics and the mystery of human performance. For those of us who seldom slip the surly bonds of earth, except to fly coach, hearing Pastrana relate the experience is kind of unsatisfying, like a giraffe explaining what it feels like to eat those leaves way up there.

“It’s like a golfer hitting a ball, except we’re the ball,” he says. “You know how far each iron and each club is going to get you and how much power you’re going to need.”

Having long since passed the axiomatic 10,000 hours to master a skill, Pastrana brings a unique suitability for flight, combining raw instinct and a deep understanding of his environment. “Travis has the knowledge and air awareness,” says Nate Wessel, who’s built many of the ramps for Pastrana’s antics. “Travis can get on something that’s never been touched before and know the speed, and he can take a lot of the risk factor out of it.”

“I don’t think there’s anybody else I’ve ever worked with who has that talent,” says Dave Mateus, who started collaborating with Pastrana as a marketing manager at Red Bull more than a decade ago. He’s kept detailed accounts in a notebook documenting every jump he and Travis have done together, and he refers to it when they’re planning new attempts. “We’ve already done it in practice, so if it’s all the same based on what we’ve surveyed, muscle memory takes over, and he nails it,” Mateus says.

To Pastrana, transparent repetition may have endowed him with a sixth sense, but to a physicist, the science of jumping stuff begins with math. “At the very basic level, it would be just your standard projectile-motion problem,” says Rhett Allain, PhD, an associate professor of physics and a science writer. “If you know the initial velocity [of an object] and the initial angle, you can find out where it’s going to go. With car jumping, I know the angle of the ramp. I know how fast it’s going. I can calculate its position every second after that and find out where it’s going to be and where it’s going to land. That’s the first-level approximation.”

Air resistance also plays a role, and a vehicle’s speed contributes to its effects. “We found that 70 miles per hour is your number,” Pastrana says, referring to the speed at which, according to his experience, air resistance has a negligible effect on a jump. “If you’re hitting a 200-foot jump [at that speed], and you do it in a golf cart, and on a dirt bike, and in a school bus, and in a semi truck—they all fly the exact same distance.”

That sounds reasonable to Allain, with a caveat: The shape of an object matters. “If you ignore air resistance, these things all move the same way,” he says. “The gravitational force depends on mass, and the change in velocity also depends on that same mass, so the mass cancels. That’s why if you drop a bowling ball and a golf ball, they have the same acceleration. It gets really complicated when you add in the air resistance. If you have a golf cart going 200 miles per hour, it’s not going to jump as fast as a different car going 200 miles per hour because the effect of air on those two will be different.”

Still, getting to the heart of Pastrana’s long career in flight—he turned 40 last year—and his instinctual relationship with physics means going back to where he started. His sprawling home in Davidsonville, Maryland, is just a few minutes from where he was born. It’s a playground of huge ramps and winding trails he calls Pastranaland. His property was also featured in his first starring role in the long-standing Gymkhana video series in 2020, in which he launched an 862-hp Subaru WRX STI nicknamed “the Airslayer” into the air at 150 mph down a tree-lined, two-lane country road.

Pastrana lives in the air above the property as much as he does on the ground.

“Among the trees out there at Travis’s house,” Mateus says, “is the history of freestyle motocross and flight. If those ramps could talk, they’d tell a story of Travis in the air. Along those trails, there’s all this history of ramp evolution, jump evolution, and creativity.”

“We base our motions off our world,” Allain says. “We started off as toddlers, we fell down, and we learned this does this and this, that does that. I don’t know the physics of falling over. I just know that if I don’t put my foot here, I’m gonna fall. [Pastrana] has been on a motorcycle for a long time. So you kind of build up that instinct.”

[image] stripped

A car-lover’s community for ultimate access & unrivaled experiences.JOIN NOW ' expand='' crop='original'][/image]

You Might Also Like