Jay Powell is trying to avoid the fate of a 1970s predecessor. Biden and Trump are making that harder.

Fed Chair Jerome Powell is facing intensifying pressure as hotter-than-expected inflation complicates his coming interest rate decisions.

The fact that both Joe Biden and Donald Trump weighed in this past week isn't making it any easier.

The situation has a historical parallel: the acute persuasion and coercion that Powell's predecessors faced during twin bouts of inflation back in the 1970s.

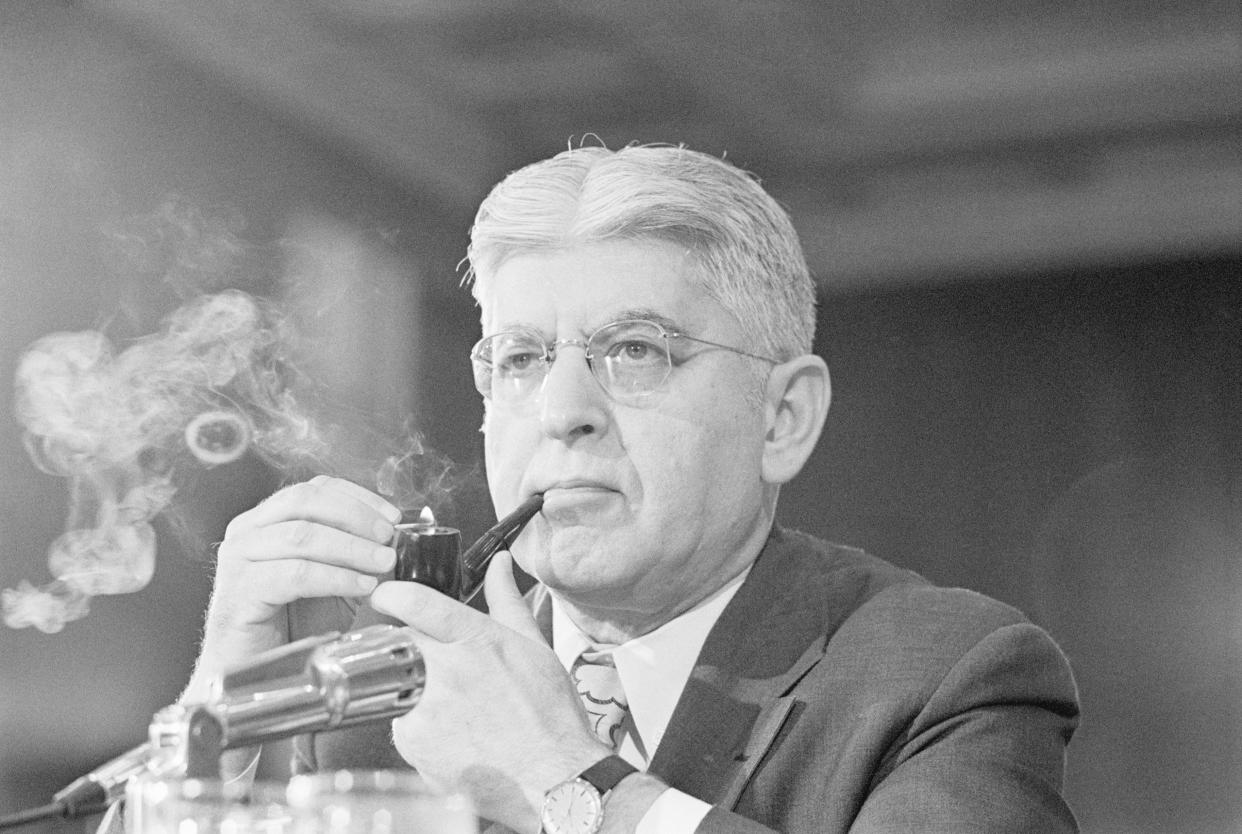

Those pressures tarnished the legacy of Arthur Burns, the Austrian-born economist who led the Fed from 1970 to 1978. The central bank's 10th chairman is often remembered as having been too susceptible to political calls for lower rates.

It's a fate Powell is clearly trying to avoid.

"It doesn't matter what the election calendar is saying," he said in a recent speech. "We are going to do what we are going to do and we will do it for economic reasons and that's it."

An array of parallels

Fed watchers have been studying the 1970s for decades in an attempt to learn both economic and political lessons from the era.

“Political pressures on the Federal Reserve were an important contributor to the rise in inflation in the United States in the 1970s,” posited professor Charles L. Weise in a 2012 paper. Weise and others also note that economic miscalculations led to some of that decade's troubles.

Former St. Louis Fed president James Bullard went into greater detail on those perceived economic errors, which he posited were why Burns "got behind" inflation.

He says the central bank of that era was perhaps too heavily focused on nonmonetary factors impacting inflation like budget deficits and oil prices and didn't move aggressively enough on interest rates as a result.

But, in any case, both the 1970s and our current era demonstrate that political pressure can be strikingly bipartisan depending on who stands to benefit.

Both periods feature presidents keen on expressing their preferences.

As Burns was being sworn in, then-President Richard Nixon even joked that the applause he was receiving was "a standing vote of appreciation in advance for lower interest rates and more money."

He added a further jibe that he respected Burns's independence but "I hope that, independently, he will conclude that my views are the ones that should be followed."

This time around, Powell has also faced years of pressure.

Trump, while serving as president, constantly pressed Powell to lower rates and even argued for negative rates when they were at zero.

Biden has been more circumspect since taking office but has proven willing to offer public commentary as of late.

Just this past week, Biden repeated a prediction that rate cuts could be in the offing this year in spite of the recent inflation news, adding the new data "may delay it a month or so, I'm not sure of that."

Pressure from Capitol Hill has also been notable.

Earlier this year, Powell appeared before Congress and faced multiple questions from Democrats about whether he should lower rates.

"Interest rates are too damn high," Congresswoman Ayanna Pressley of Massachusetts told him in one colorful moment.

The pressure in the 1970s was even more overt and in one case took the form of a congressional resolution urging the central bank to "pursue policies in the first half of 1975 so as to encourage lower long term interest rates."

The resolution was sponsored by Rep. Thomas Rees, a California Democrat, and it passed both chambers of Congress by wide margins including a unanimous 86-0 tally in the Senate.

The pressure for lower rates is a feature Fed chairs often confront and one that, for Powell, could change in November only insofar as who is doing the pressuring.

Republicans from Trump on down are currently adamant that Powell keep rates high. "The Fed will never be able to credibly lower interest rates," Trump posted to social media this week, charging that Powell was trying to "protect" Joe Biden.

But few expect Trump to keep that posture up if he wins in November and finds himself in a position to benefit politically from looser monetary policy.

A desire to be remembered as a Volcker, not a Burns

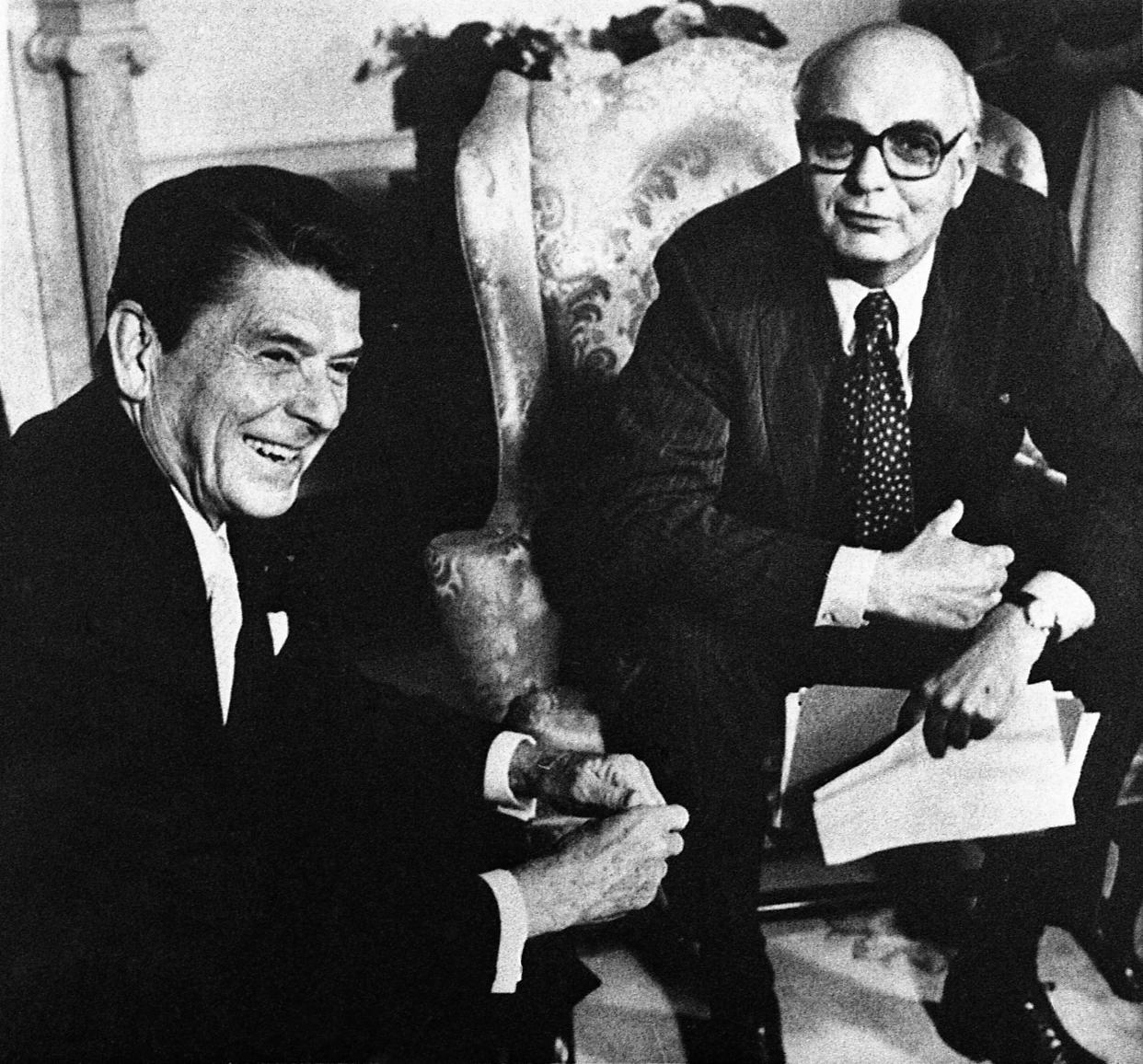

Powell is clearly hoping to have a legacy more akin to Paul Volcker, who chaired the Fed from 1979 to 1987 and tends to be remembered as the leader that finally broke the back of inflation.

But even Volcker faced an array of political pressures.

Interest rates went up and down for years after Volcker took the reins in August 1979. He immediately had to navigate a 1980 election season before he was able to raise interest rates to 20% by 1981, still the all-time high.

But even then the pressure for lower rates was just around the corner. In 1984, Ronald Reagan and his chief of staff, James Baker, summoned Volcker to the White House and — according to the telling in Volcker's memoir — ordered him not to raise interest rates before that year's election.

"I was stunned," wrote Volcker, but he added that he was able to not escalate the episode, as "I wasn't planning tighter monetary policy at the time."

Instead of responding one way or another, Volcker says he simply left the meeting without saying a word.

He guessed — in an echo of the still-recent Watergate scandal — that the meeting had taken place in the White House library instead of the Oval Office because Reagan didn't want to be caught undermining Fed independence and that the room "probably lacked a taping system."

Ben Werschkul is Washington correspondent for Yahoo Finance.

Click here for politics news related to business and money

Read the latest financial and business news from Yahoo Finance