American workers are slowly regaining power

American labor lost out during the last 40 years. Union membership fell by half, millions of manufacturing jobs went to China, the middle class shrank, and wealthy Americans captured most of the income gains.

Workers may finally be regaining power, due to a combination of factors: President Joe Biden’s pro-worker policies, protectionism in both political parties, labor shortages in some industries, and shifting economic priorities in society as a whole. The gains are fragile, for now, and might not last. Voters may not even care that much, and they could unwittingly usher in a reversal.

Yet every week, some small development seems to signal that ordinary workers are catching a break. On April 23, for instance, the Federal Trade Commission (FTC) banned noncompete agreements, or NCAs, for most workers, which could make it easier for some 30 million people to leave one company for another in the same business.

Noncompetes evolved as a way to keep senior executives with deep corporate knowledge from taking legally protected trade secrets to a competing firm. But businesses began to apply NCAs to ordinary workers with no special knowledge, effectively preventing them from job-hopping for better pay. The FTC now plans to ban NCAs except for senior executives.

The business lobby is suing to block the ruling, which could delay it or kill it. If Donald Trump ousts Biden in this year’s presidential election, he’d probably roll back the rule as a part of a renewed pro-business, deregulatory push. But several states have been imposing their own bans on NCAs, and it feels like progress to see the federal government attempting to set a national standard for a practice with limited applicability that employers have been abusing for more than 20 years.

The Biden administration also recently changed the federal rule for overtime pay so that more middle-income workers qualify. Business groups seem certain to challenge that change too, and both issues could make it to the Supreme Court in coming years. But even that would give the issue of worker rights more prominence.

It’s worth noting that Biden failed in his first effort to forgive student debt for more than 40 million Americans when the Supreme Court shot down the whole thing last year. But Biden came back with a series of smaller, more targeted debt relief plans designed to fare better against legal challenges. Altogether, Biden’s follow-up plans now forgive some debt for nearly 30 million people, not far from the original goal. That in itself leaves workers more take-home pay to spend on housing or other priorities.

Drop Rick Newman a note, follow him on Twitter, or sign up for his newsletter.

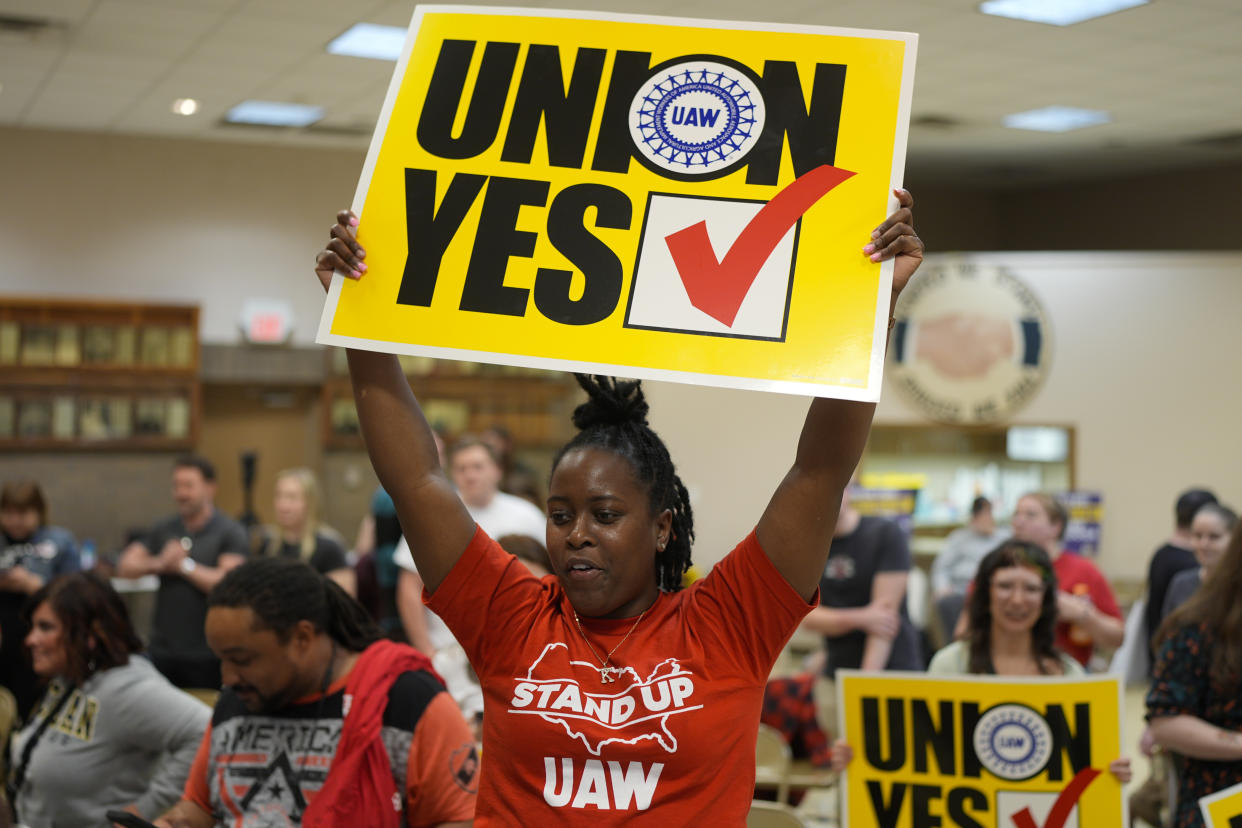

Not every workplace change stems from government action. This month, the United Auto Workers (UAW) successfully unionized Volkswagen’s plant in Chattanooga, Tenn., the first auto plant in the South to vote for union membership. The history is important here. The UAW tried to unionize the VW plant twice before, in 2014 and 2019. It failed both times.

What changed? A couple of things. First, the UAW scored its first big victory in years last fall when it won big pay and benefit gains from General Motors (GM), Ford (F), and Stellantis (STLA) (formerly Chrysler). That followed bitter union losses after GM and Chrysler declared bankruptcy in 2009, and a long period of union soul-searching. Part of the union’s recovery included a sharp improvement in public approval of unions, from a low of 48% in 2010 to 67% in 2023. Americans increasingly see unions as a way to redress economic trends that have disfavored workers.

Biden gave the UAW a bit of an assist last year when he was the first president ever to show up on a picket line and advocate for striking workers. Or maybe it will be the other way around, with the union giving Biden an assist. Biden basically had the foresight (or good luck) to guess right about the outcome of the UAW strike and line up with the winning side. With the UAW now vowing to target other southern states for unionization, Biden appears to be aligned with the national mood on an important workplace trend.

A manufacturing renaissance could be one trend that withstands a change in political leadership. Trump tried to boost US manufacturing during his own presidency, mainly through tariffs that made imports more expensive. The main result, however, was a shift in imports away from targeted countries — mainly China — to other countries, such as Vietnam and Mexico, not subject to Trump’s tariffs.

Biden has taken a different approach, signing into law major incentives for building more key technologies in the United States, including semiconductors and green energy equipment. That effort is working. Manufacturing construction began to skyrocket in 2022, with spending on factory construction up 128% during the last two years. Once those factories open, a boom in manufacturing employment is sure to follow, with many of those jobs being higher-skilled advanced manufacturing positions that pay well.

All of this comes with the economy in a three-year boom that continually defies forecasts of a recession. Employment growth since the COVID pandemic receded in 2021 has been the strongest ever in a three-year period, and the demand for workers has benefited many left out of prior booms. Wage growth during the last few years has been strongest among the lowest-paid workers, for instance.

So American workers must feel elated, right? Um, anything but.

Americans are notoriously gloomy, with some consumer confidence surveys near recessionary levels and 75% of Americans feeling dissatisfied with the direction of the country. Biden’s approval rating has been stuck around 40% for two years, a remarkably weak rating for an incumbent amid low unemployment and record job growth.

It’s possible that workplace improvements making news headlines still feel intangible or elusive on the job or are too minor to improve the national mood. Other improvements have been hard to come by. While some states and localities have raised their minimum wages, for instance, the national minimum is still a paltry $7.25 per hour, and it hasn’t been raised in 15 years.

It’s also true, as some conservatives point out, that a vibrant economy propelling workers forward isn’t something the government can just dial up through rules or laws. A careful balance between regulation and innovation is crucial, and too much of one can mean too little of the other.

If a manufacturing renaissance or a workplace revival really is underway, we’re probably at the early stages, with further progress depending on future decisions. A Joe Biden reelection would keep the workplace regulations flowing, while a second Donald Trump term would probably mean fewer rules on businesses, more tariffs on imports, and an uncertain impact overall. If workers are truly ascendant, they may still need a helping hand to climb the next rung or two.

Rick Newman is a senior columnist for Yahoo Finance. Follow him on Twitter at @rickjnewman.

Read the latest financial and business news from Yahoo Finance