What Is 'Film Noir'? A Guide to the Classic Movie Genre

Barbara Stanwyck and Fred MacMurray in film noir classic 'Double Indemnity.'

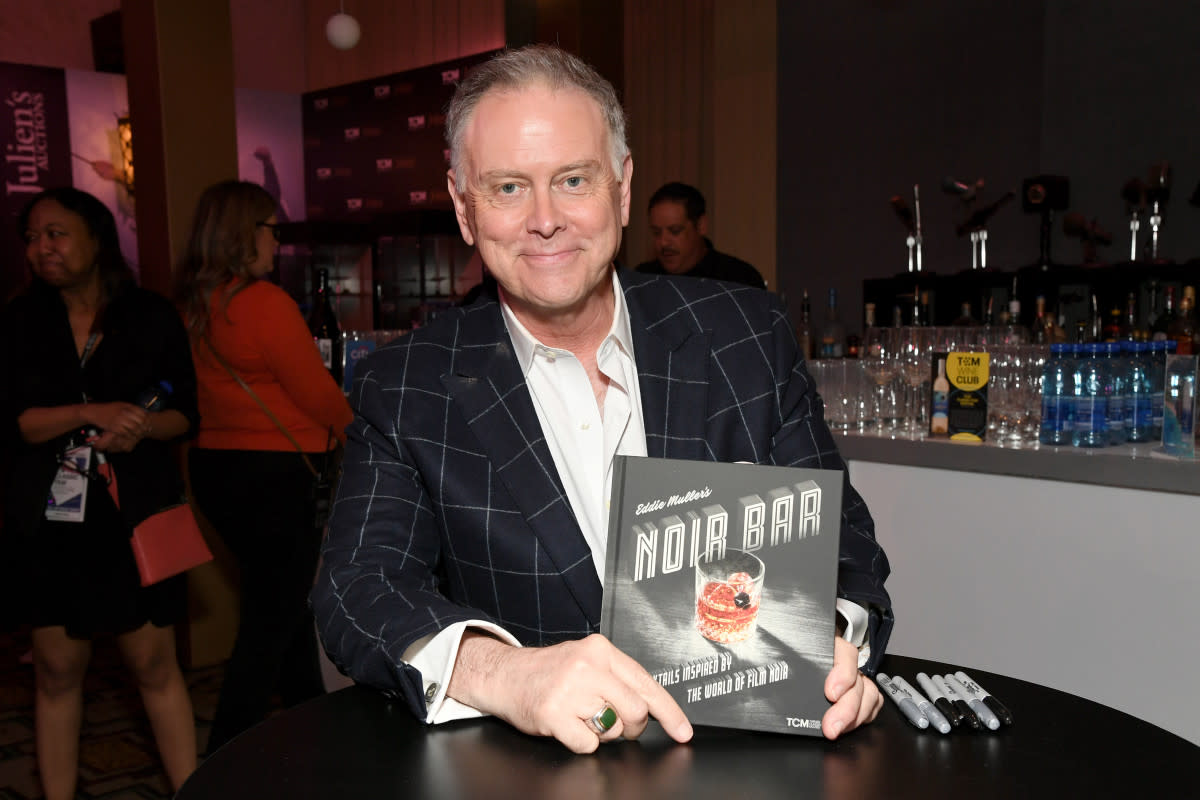

Eddie Muller likes his coffee the same way he likes his movies: unsweetened and dark.

Muller, 64, the host of Noir Alley on Turner Classic Movies, is taking a wake-up sip of morning joe in his California home. Fans of TCM know him as the host of the network’s weekly series all about film noir, retro-stylish Hollywood crime drama with cynical guys, dangerous dames, risky liaisons and dark, dirty deeds. Viewers tune in each week for his “guided tour through the crime-infested streets of classic cinema.”

Photo by Jon Kopaloff/Getty Images for TCM

Just as with Muller’s mug of black coffee, there isn’t much sweetener in noir, either. Noir is “technically the French word for ‘black,’ but it’s used to mean darkness,” says Muller, who has written 11 books on the subject, including Eddie Muller’s Noir Bar, with cocktails inspired by noir movies, and his first “kid noir” book, Kitty Feral and the Case of the Marshmallow Monkey.

How dark is noir? There are long shadows, shady characters, gloomy streets, inky nights and dimly lit rooms. In fact, classic noir movies, from the 1940s and ‘50s, were almost always filmed in black and white, providing stark visual contrasts—and unmistakable metaphors for right (light) and wrong (dark). And characters frequently surrender to dark desires that detour them into places where bad things can happen, and do.

Related: The 75 Best Psychological Thrillers of All Time, From 'Gone Girl' to 'The Lost Daughter'

All that darkness, Muller says, represented the disillusionment and disenchantment of Americans—specifically filmmakers—who’d lived through the dismal days of the Great Depression, only to transition into another period of bleakness with World War II, then finally come out on the other side with an all-new set of anxieties, fears, doubts and dread. During those days, things looked dreary for a lot of people, and movies began to show it.

Most of Hollywood’s biggest stars of the era—Humphrey Bogart, Lauren Bacall, Robert Mitchum, Orson Welles, Barbara Stanwyck, Marilyn Monroe, James Cagney—made noir movies, many of which are considered classics today. And you’ve probably seen noir, but maybe didn’t realize that’s what you were watching.

"You might very well love the films," says Muller, who runs the Film Noir Foundation, a nonprofit created to study, explore and preserve noir movies, but “not know this very special term that applies to them” or that this genre is alive and well in modern times. Nightcrawler (2014) starring Jake Gyllenhaal was definitely a bleak, new-noir thriller. Guillermo del Toro’s Nightmare Alley (2021) with Bradley Cooper was another.

How did noir get started?

Photo by Warner Bros./Getty Images

Before WWII, there were crime dramas—movies about gangsters, cops and robbers and notorious ne’er-do-wells like Al Capone, Babyface Nelson and Bugsy Malone, or crusading fictional crime busters including Dick Tracy and Charlie Chan. But during the war years, filmmakers felt a sort of patriotic duty to make uplifting, rah-rah, good-guy, “apple pie” movies. “Hollywood kind of saw it as its duty to get us through that,” Muller says.

But as the 1940s unfurled into the ‘50s, there were other dark days ahead. The atomic bombs that ended WWII ushered in an era of Cold War paranoia, followed by McCarthyism and the Red Scare. At the same time, many talented German filmmakers came to America and “brought their particular, darker styles with them,” Muller says.

When the war ended, filmmakers, novelists and screenwriters were emboldened “to write things that didn’t have happy endings, that could be a little edgier and say things about the culture that weren’t always positive,” he says. “Noir represented a very crucial moment in history, when America started to lose its innocence.”

French critics took notice and dubbed these new American crime dramas noir for their dark views on life. The name stuck, and the genre grew in the 1950s with films like The Night of the Hunter (with Robert Mitchum), Orson Welles’ Touch of Evil, director Billy Wilder’s classic Sunset Boulevard, Alfred Hitchcock’s Strangers on a Train, Stanley Kubrick’s The Killing, Fritz Lang’s The Big Heat, John Huston’s The Asphalt Jungle and hundreds of others.

What are the key elements of a noir film?

Bettmann / Contributor / Getty

There is a lot of debate over what makes a movie “noir.” “I don’t know of any other movie genre where that is the case,” says Muller. “Like, nobody debates whether a movie is a Western or a musical or a screwball comedy.” He often runs a segment on TCM called “Noir or Not,” which sets the record straight. One thing noir is not is true crime. Film noir, he says, is like watching characters grab pieces of forbidden fruit; true-crime is more like gobbling from an all-you-can-eat buffet.

Here are some common traits of a noir film:

Anitheroes

True noir movies aren’t about heroes or heroics. “They’re [typically] about average people who realize they’re capable of doing something horribly wrong, and they do it anyway,” he says. “The disillusioned antihero is probably the most common protagonist in film noir. They realize the only way they’re going to get something they want is by breaking the law,” like knocking over a bank, defrauding an insurance company, or committing a murder.

“It can even be a police officer or someone who starts out on the ‘right’ side of the law, like in Shield For Murder (1954), Where the Sidewalk Ends (1950) and The Prowler (1951). That’s very common in noir.” In modern-day TV, Breaking Bad (2008-2013) leans noir. “A mild high-school teacher ends up doing things he never realized he was capable of,” Muller says. “I thought it was fantastic.”

Fate & unfairness

Some noir movies offer meaty topics to ponder, like “the indifference of fate and the unfairness of the system,“ Muller says. “A guy comes back from the war; he's broke, he can't get a job; he falls in with a crook that they rob banks. In the right hands, these turn into very strong social commentaries.”

Some people tell Muller that noir films are depressing and pessimistic, and he can’t argue with that. “Yeah, they are,” he says. “But they’re like warning flares; tales of karma; morality plays about what happens when you succumb to your worst temptations…which never ends well.”

United Artists

Good girls & femme fatales

Women also play significant roles in noir. “Historically, a lot of people have written—and I think mistakenly—that film noir is misogynistic because it presents a kind of negative view of women as vixens or vipers,” he says. “But in truth, the women of noir are surprisingly progressive for their era. They’re often self-sufficient, self-reliant women who are nurses or doctors or fashion designers or magazine editors.”

And typically, he says, “there is a woman in the movie who’s depicted as the only hope of salvation for the desperate, tempted man. But he always makes the wrong decision and then ends up paying the price.”

Some of Muller’s favorite noir females include Ella Raines, a Washington-born actress who appeared in dozens of films—of all sorts—alongside John Wayne, Randolph Scott, Burt Lancaster and other of leading men of the day. “She specialized in playing good, sensible women. She was incredibly beautiful, but she never played the femme fatale,” a movie archetype—and another French term—for an attractive woman who typically spells doom for men that become involved with her.

Related: We Ranked the 101 Best Thrillers of All Time, From 'Psycho' to 'Parasite'

“In Angel Face, Jean Simmons is the spoiled heiress who tempts Robert Mitchum. But Mitchum has a very sensible girlfriend, a nurse played by Mona Freeman, who is clearly the woman he is supposed to be with.”

Muller also cites two of the queens of noir, Joan Crawford and Barbara Stanwyck, noting that they sometimes played protagonists in lead roles equally capable of making bad decisions—just like noir men. “Stanwyck in Double Indemnity, of course,” says Mullen, “but also, The Strange Love of Martha Ivers, The Lady Gambles or The File on Thelma Jordan—all movies in which she is the desperate one, often leading to her downfall.”

More recently, Body Heat (1981) with Kathleen Turner and William Hurt fits the noir profile: Turner’s femme fatale Matty Walker convinces her small-time lawyer lover (Hurt) to kill her husband. Falling into bed with her was just his first mistake.

Plot twists

Noir films are usually complicated and multilayered, full of twists and turns for both males and females—and often those turns turn out to be deadly. “One of the features of a lot of noir films is complex storytelling,” Muller says. “You get a lot of flashbacks. And generally, it's tales where the protagonist is doomed and he's telling you his story, explaining how he came to be on death row, or lying in the gutter as he bleeds out. That's very noir.”

Related: The 20 Best Crime Movies on Netflix Right Now

Great writing & dialogue

Many of the greatest noir films are based on or inspired by novels from writers like Dashiell Hammett, James M. Cain, Mickey Spillane, Dennis Lehane and Patricia Highsmith, who Muller calls one of the greatest noir writers of all time. Her novels have been adapted into more than 20 films, including Hitchcock’s Strangers on a Train, The Talented Mr. Ripley, Deep Water and The Price of Salt—and later this year into a Netflix series called Ripley. “She’s fantastic and just so prolific,” he says.

Is film noir around today?

Universal Pictures

Although film noir has its roots in the past, it is a genre that is very much alive in the present.

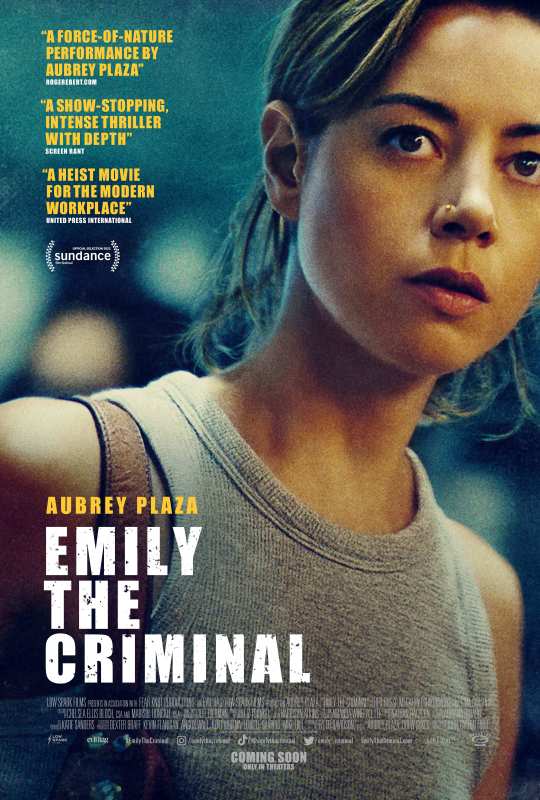

Muller points to some recent flicks that put new twists on the format. “The film Emily the Criminal with Aubrey Plaza, last year, was like classic noir. And another recent one, I’m Your Woman with Rachel Brosnahan. That was very much in the tradition of noir, where they get in, tell the story and wrap it up in less than 90 minutes.” Decades ago, he says, the noir story in I’m Your Woman would have been about the mobster husband, and likely told in flashback—not following the wife as she makes her way in the world after he’s gone.

Muller is eager to watch as even more females take leading roles as noir continues to transition into the modern era. “I’m interested in seeing how storytellers adapt it for contemporary times,” he says. “It makes perfect sense to me that we’ll be seeing more stories with female protagonists.”

It makes sense that we’ll be seeing more noir, period, he says because film noir, and how it came to be, is “important not just because it’s cinematic history, but it’s history, period. My goal is to get people to watch the movies, to think a little bit more about what went into them, and what they mean to the culture at large.” And he hopes that audiences of all ages won’t hesitate to join him—in the dark.

Next, 8 Must-Watch Film Noir Movies Picked By Expert Eddie Muller