Ferrari's Impossible Le Mans

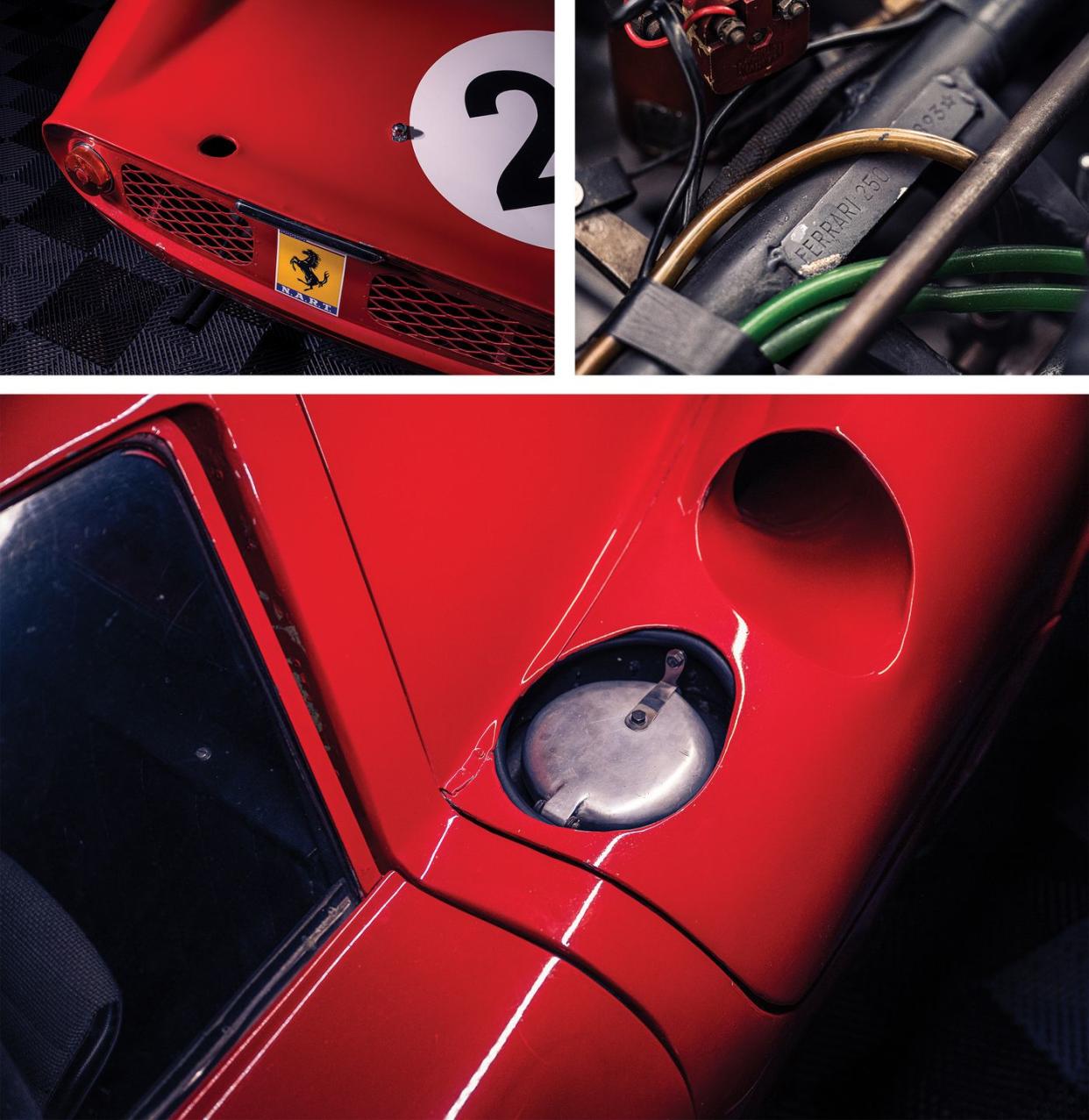

Luigi Chinetti’s Ferrari 250 LM came to the 1965 24 Hours of Le Mans stinking of also-ran. The 250 LM was pretty, but Ferrari had moved on to beasts like the 275 GTB Competizione Speciale and 330 P2. When the FIA wouldn’t classify the mid-engine 250 LM as a GT, Ferrari gave up on the tiny Berlinetta and sold off examples to customers—privateers who were background fillers in international sports-car racing. Chinetti’s 250 LM, running as a prototype, was there to lose.

This story originally appeared in Volume 16 of Road & Track.

“There were 51 starters in the Le Mans race,” wrote Denis Jenkinson for MotorSport magazine, “but to all intents and purposes, it was a straight fight between Ferrari and Ford.” It was a titanic struggle between two factories (one small, one huge) and two countries (one small, one huge), all obsessed with victory.

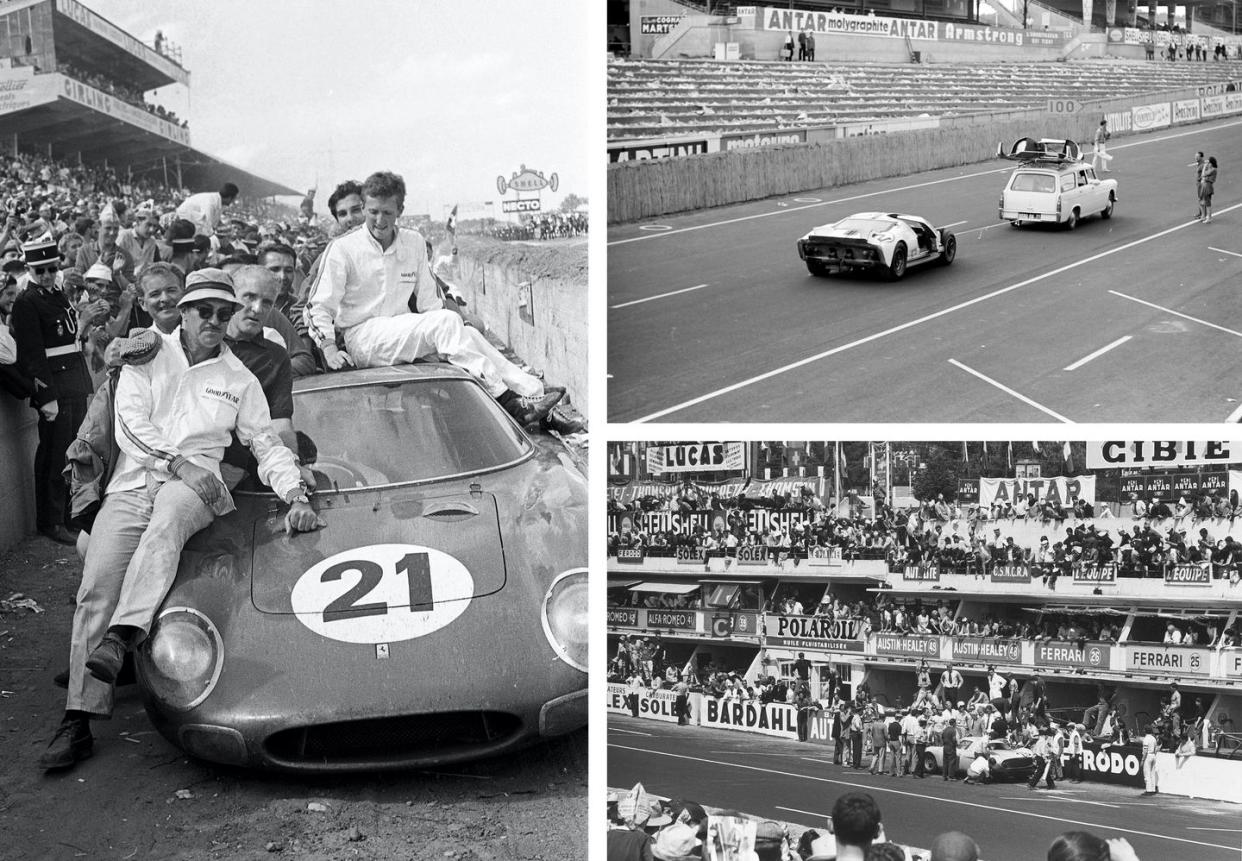

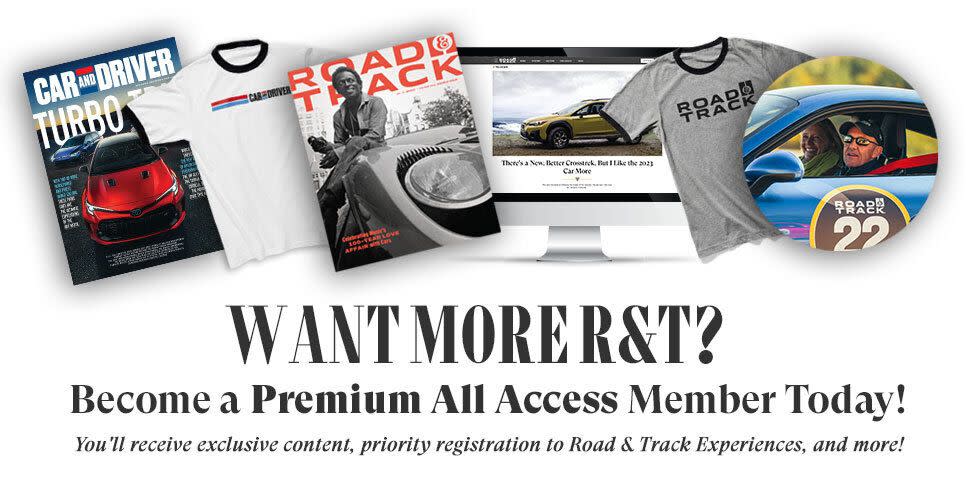

The 1965 Le Mans was the last time a Ferrari won the great race. But it wasn’t the Ferrari factory that earned the victory; it was Chinetti’s North American Racing Team (NART). And that slight distinction would further rattle Enzo Ferrari during one of his toughest years. Ferrari—the luxury brand and indomitable business it is today—emerged out of Enzo’s frustration.

Also, it pissed off Ford.

Even before the 1965 race, things were haywire. During practice in April, Lloyd Casner died after being thrown from his Maserati Tipo 151/3. Practice on June 16 was canceled because of high winds. Early on the day of the race, June 19, a truck carrying concession supplies collided with a car outside the circuit. Five died in the fiery crash. Far less tragically, ABC Sports was going to broadcast the race’s start live to America over the miracle of the “Early Bird” satellite, but a ground-station failure thwarted that. Nothing went as expected. Except that the cars were fast.

“The first 17 cars in line for the Le Mans start were either Ferrari or Ford, the slowest one lapping at 126.154 mph, and their numbers were almost exactly split,” explained Road & Track’s Henry Manney. “Five prototypes for Ferrari plus lots of LMs and one GTB, six Ford GTs and a hiss of Cobras for the great Dearborn firm. Ferrari had the inestimable advantage of its sharp-eared corps of racing mechanics plus drivers who were Ferrari drivers; Ford brought an army of 50 people plus enthusiastic and stellar talent like P. Hill, McLaren, Amon, Whitmore, Bucknum, et al. . . . Ferrari was calm, Ford was jittery.”

The quickest car was Chris Amon and Phil Hill’s Shelby-prepared Ford GT Mk II. Powered by a 485-hp 7.0-liter V-8 based on those used in NASCAR’s 3700-pound Galaxies, the 2800-pound Mk II walloped down the Mulsanne at over 300 km/h. Close enough to 200 mph. In practice, the Mk II ran the 8.36-mile course in 3 minutes, 33 seconds—nine seconds quicker than 1964’s best practice time. That’s an average of 141.37 mph and five seconds quicker than the 4.0-liter V-12–powered Ferrari 330 P2 driven by John Surtees and Ludovico Scarfiotti. Three Ford GTs and the Surtees Ferrari all hit at least 300 km/h on the Mulsanne.

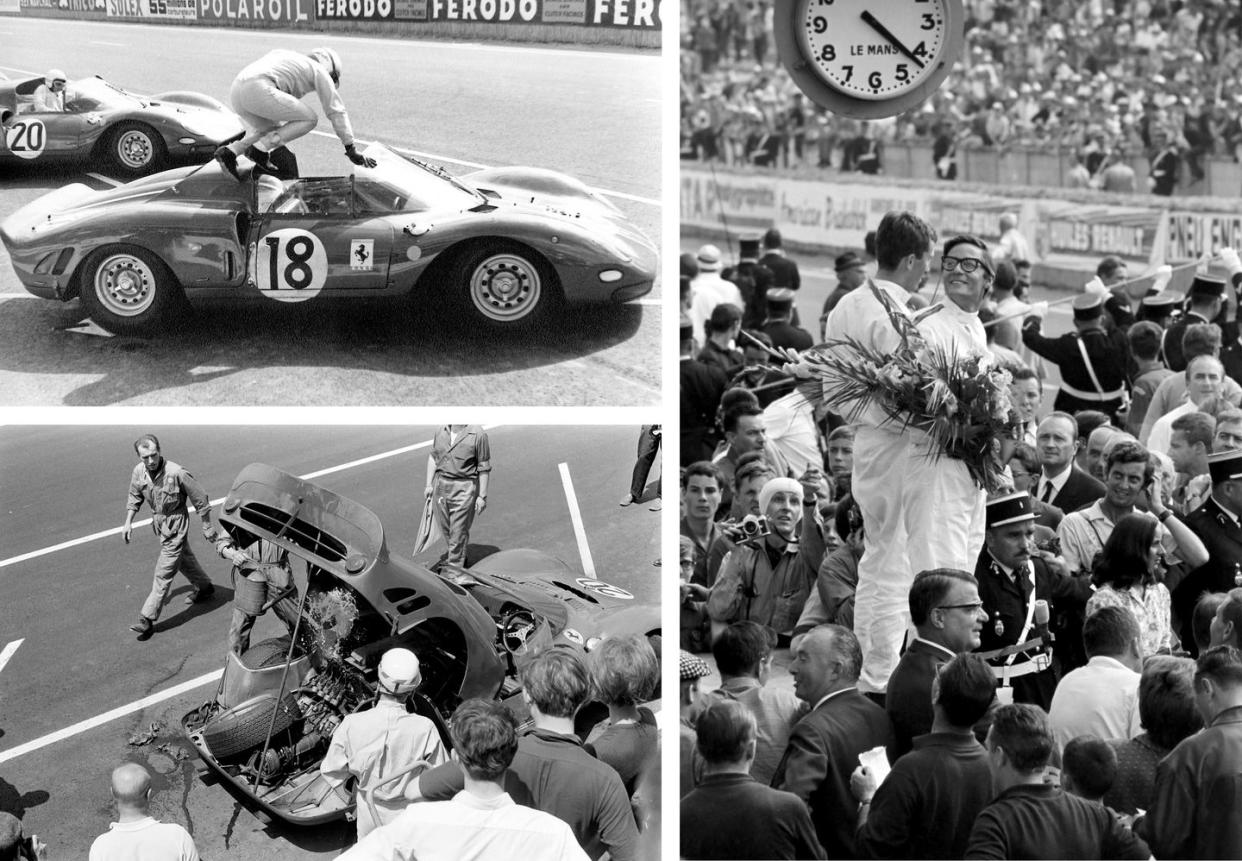

Meanwhile, the NART 250 LM was the quickest of its type. With Formula 1 pilot and crazed German 23-year-old Jochen Rindt driving, it qualified 11th with a 3:45.7 lap time. That was quicker than Ford of France’s open-cockpit 4.7-liter GT40, all the Cobra coupes, and the four other 250 LMs campaigned by the Belgian Ecurie Francorchamps, Italians Maranello Concessionaires, Scuderia Filipinetti, and Frenchman Pierre Dumay. Rindt’s co-driver was Masten Gregory, a 33-year-old American who wore thick, black-rimmed glasses to counter his lousy eyesight.

NART had also entered a 365 P2 Spyder for Pedro Rodríguez and Nino Vaccarella. It qualified sixth, making it the NART machine likely to finish best.

Jo Siffert’s Maserati Tipo 65 blasted to an early lead but was reeled in by the Fords and Ferraris. By the end of the first lap, Bruce McLaren was leading in one of the two Ford GT Mk IIs. Behind him was Amon in the other Mk II, then Surtees in the factory 330 P2. But the NART 250 LM had nothing to lose, and Rindt was so fast.

“During practice, Rindt was not comfortable with Gregory’s strategy of a conservative pace,” recalled NART team manager Ed Hugus in Robert D. Walker’s book, Cobra Pilote: The Ed Hugus Story. “Rindt’s philosophy was to run the car at the maximum limit. If the Ferrari held together, the team would have a good chance of winning. If the car developed a mechanical problem and could not go the distance, they would quickly be out of the race and Rindt could go home.”

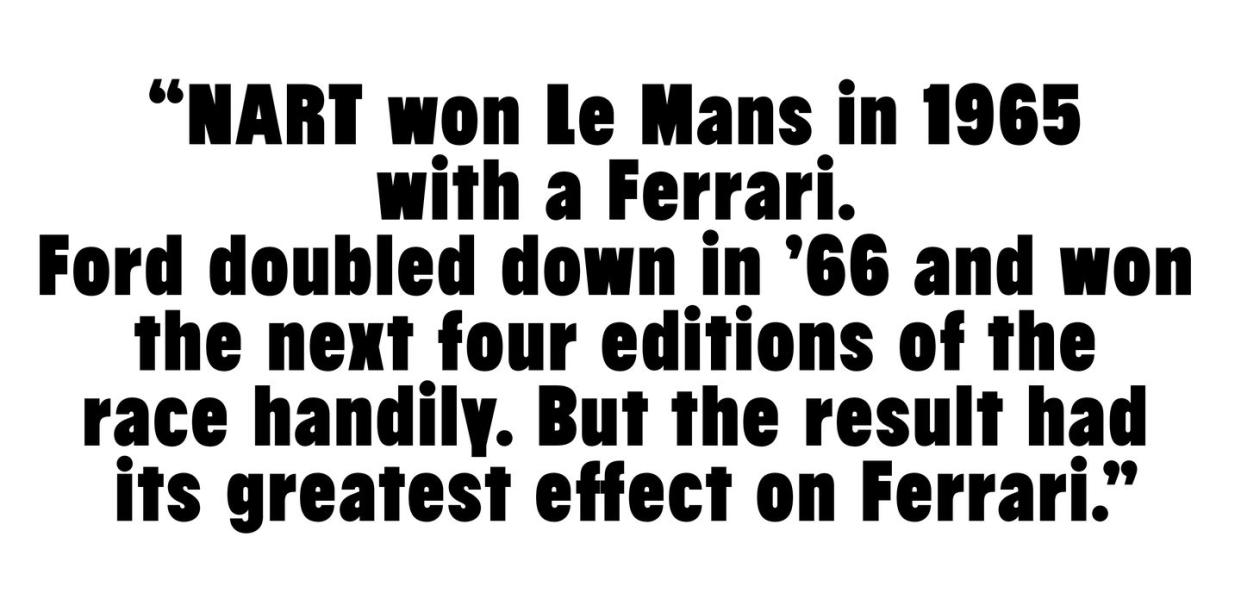

Shelby’s Mk II set a blistering pace initially, and the massive mound of money Ford spent seemed destined to pay off. Then, Ford of France’s GT40 Spyder chunked its gearbox in the second hour. “Bondurant was the second to go,” reported Manney about the Rob Walker–entered GT, “around 6 p.m. when the head lifted and let all the water out.” A few minutes later, the GT entered by Scuderia Filipinetti also blew a head gasket on its 5.3-liter small-block V-8. Shelby’s Ken Miles/Bruce McLaren Mk II ate its gearbox in the fourth hour. The Hill/Amon Mk II died of a broken clutch in the seventh.

Soon the only Ford GT coupe left was the British entry of John Whitmore and Innes Ireland, “and that was mighty ill after rising to seventh slot,” wrote Manney. “The fiber cam-follower on the contact breaker had worn itself down, possibly because nobody had remembered to lubricate it in the struggle, and the engine commenced to run very hot. Having boiled most of the water away, it was sent out to do ten gentle laps until refilling was permitted, but ten were too many. Ireland brought it in to a stinking halt at 9:30 p.m. and while gay music jangled over the loudspeaker, there it sat and sizzled itself to death. The last of the big spenders was gone.”

It seemed that Enzo Ferrari would, once again, have his way.

But if one person could resist Enzo, it was Luigi Chinetti. A three-time Le Mans winner as a driver, including taking Ferrari’s 166 MM to the team’s first victory in 1949, he left Italy for America when World War II broke out. The war, however, didn’t break his relationship with Enzo, and by the early Fifties, he was the sole American distributor of Ferraris. Chinetti instinctively knew what Americans wanted in a Ferrari and was the motivating force behind the brawny “America” series of Ferraris that would establish the brand in what would become its most reliably profitable market. Soon to turn 64, Chinetti was secure enough in 1965 to tell Enzo, if necessary, to go screw himself.

Enzo Ferrari rarely (if ever) left Italy, but he was an overwhelming nonpresence. And 1965 wasn’t going well for him. At all.

As 1965 began, the FIA kept Ferrari’s new 275-series cars from running in the GT category. In protest, Enzo pulled out of the GT Championship. Though the Scuderia took the 1964 F1 drivers’ and constructors’ championships, it was getting skunked in ’65. Ferrari the man was turning 67. His mother, with whom he had always lived, was dying, and he didn’t get along with his wife. He had lost his beloved son Dino to muscular dystrophy back in ’56 and hadn’t yet acknowledged his other son, Piero, whose mother was Enzo’s mistress. One of his frustrated former clients, Ferruccio Lamborghini, was now building road cars to better Ferrari’s. Plus, the Ford Motor Company, which made more than 3.3 million vehicles in 1965, was out to destroy him.

At Daytona in January, Ken Miles and Lloyd Ruby’s 4.7-liter Ford GT won the 1965 World Sportscar Championship opening round while slaughtering Ferrari’s new 4.0-liter 330 P2 prototype. It got worse when something called a Chaparral, built by Texans Jim Hall and Hap Sharp and powered by a Chevrolet truck engine, shit-kicked the competition at March’s 12 Hours of Sebring.

Enzo felt the pressure. Not that he shared anything with anyone. Il Commendatore saw the future in 1965 and knew change was inevitable. He couldn’t simply impose his will any longer.

But Enzo was winning again at Le Mans after the Fords collapsed. Surtees and Scarfiotti, in the No. 17 car, were practically loafing, with their 330 P2 turning 3:42 laps, which is about a 130-mph average clip. When a front spring cracked apart and changing it dropped the big red car to fifth, the win still seemed guaranteed. Even after the factory entry dropped to 10th when the team had to pull brake discs off the Lorenzo Bandini/Giampiero Biscaldi 275 P2 and transfer them to Surtees’s machine, victory appeared inevitable.

Then Bandini’s car lost a head gasket in the 17th hour, and Surtees’s car spat out its clutch assembly in the 18th. That left Mike Parkes and Jean Guichet’s 330 P2 as the last factory Ferrari entry in the race. The P2 was charging back despite a gearbox locked into fifth gear. What Enzo also had (sort of) were the privately owned entries—including four of the five 250 LMs.

The 250 LM was a proven package in 1965. At its core, it was a closed Berlinetta version of the open 250 P that had won the 1963 Le Mans. Coyly described as a mid-engine version of the legendary 250 GTO, it was among Ferrari’s first mid-engine cars and built of robust, familiar components. The 320-hp 3.3-liter V-12 in its tail wasn’t overwhelming, but it wasn’t likely to lift a head gasket, destroy a clutch, or kill a gearbox. Rindt’s bet on going flat out for all 24 hours wasn’t that irresponsible. Slightly insane but not irresponsible. Not that Rindt seemed to care that much.

At around 4:00 a.m., fog engulfed the circuit, and Gregory’s glasses were hazing over. Plus, he had lousy night vision and sore eyes. He pulled in for an unscheduled stop, but Rindt was nowhere to be found. So Hugus suited up, got in the car, and drove for the last hour of Gregory’s shift. None of the officials noticed.

“Luigi told me many times later that he had informed the pit official about this,” Hugus wrote in a handwritten note to a friend. “However, as Luigi said, maybe they were too busy with a wine bottle behind the pits to do so. He was disappointed and so was I. Say la vie [sic].”

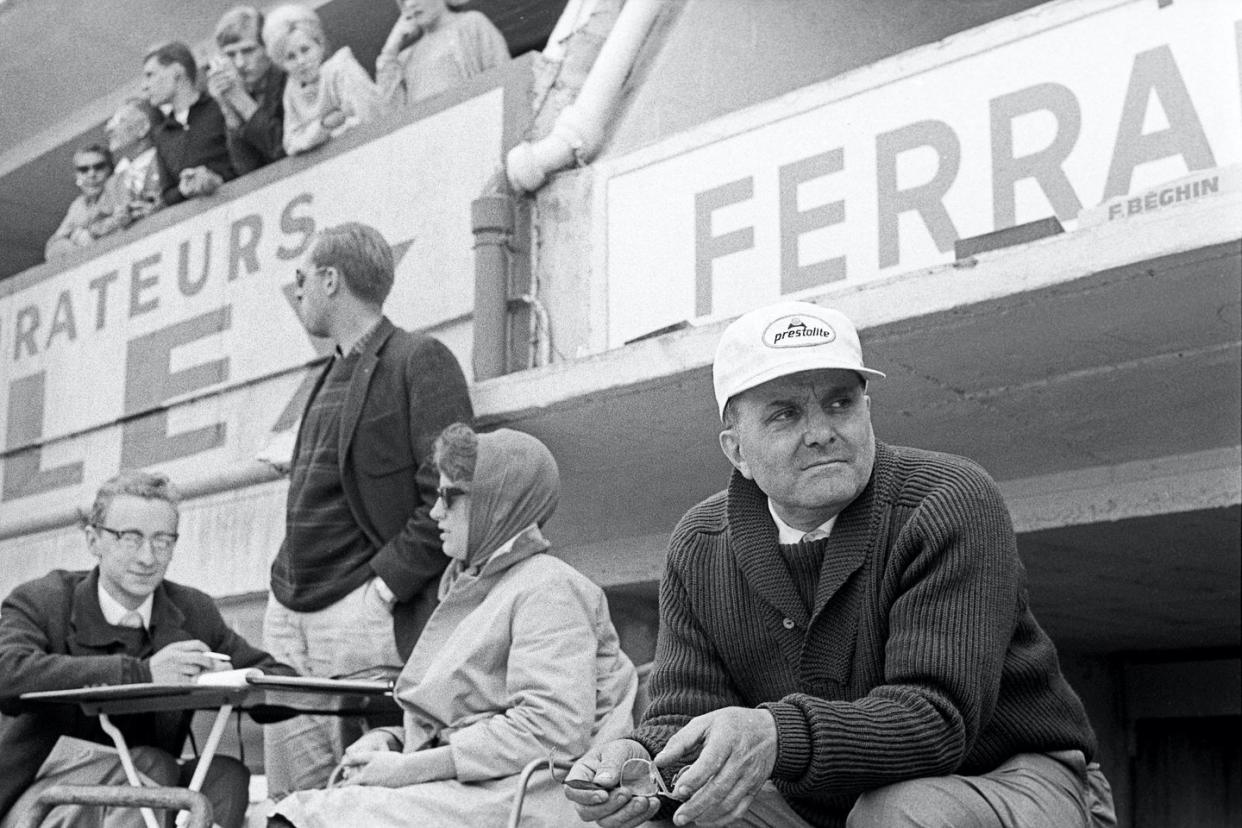

Hugus, a World War II veteran who would turn 42 that June, had an under-the-radar career that included working alongside Shelby on the original Cobra, being the first Shelby Cobra dealer, competing as one of America’s top amateur road racers, and driving in every Le Mans from 1956 through 1964. “I arrived at Le Mans [in 1965] and expected to drive my own NART Ferrari entry, which was to have been delivered at the track by the Ferrari factory in time for pre-race practice,” Hugus is quoted as saying in Walker’s book. But the car wasn’t done, and Hugus was instead installed as team manager by Chinetti and designated as a relief driver to the Rindt/Gregory effort. No one, however, seems to have informed the Le Mans officials of such a designation.

Improbably, the NART 250 LM was moving through the field. With the last works Ferrari hobbling in third, the race came down to the red NART 250 LM and a yellow 250 LM entered and driven by Pierre Dumay and Gustave Gosselin. Meanwhile, the NART 365 P2 Spyder was chugging along and would finish seventh.

With the yellow French 250 LM on Dunlops and the American entry on Goodyears, tires became a contentious issue. Rumors were that the Ferrari team tried to convince both 250 LMs to slow down so the limping 330 P2 could win. It wanted the winner on Dunlops, as Ferrari was under contract with that brand of rubber. Thus, Chinetti was under pressure to slow his car down and let the Dumay/Gosselin car win. But Chinetti, no matter how many additional Ferrari road cars he may (or may not) have been offered to line his showroom floors by Signor Ferrari as an inducement, refused to slow down his machine.

Then the works 330 P2 finally ground up the last of the cogs in its gearbox in the 23rd hour after 315 laps. It was the top nonfinisher—no comfort to Enzo.

NART won Le Mans in 1965 with a Ferrari. Ford doubled down in ’66 and won the next four editions of the race handily. But the result had its greatest effect on Ferrari.

In March 1965, a small story in the New York Times announced that Ferrari would cooperate with Fiat in building a Formula 2 car. Shortly after Le Mans that year, Fiat took a small stake in Ferrari. That led to the co-production of two new “Dino” models powered by a Ferrari-designed V-6 manufactured by Fiat and built to sell in commercially significant volumes.

Ferrari began evolving into a car company, a luxury brand and not just a win/loss record. It wouldn’t be a trivia question like Bizzarrini, Cisitalia, or OSCA. And 1965 was when it became an enterprise that would outlive Enzo himself. It’s why there’s a Ferrari theme park in Abu Dhabi and why, right now, someone is lying out in the sunshine on an officially licensed Cavallino Rampante beach towel.

You Might Also Like