How a Ferrari-Obsessed Bureaucrat Gave America the 25-Year Rule

For those who weren’t alive or paying sufficient attention, it’s hard to explain how grim the Seventies and Eighties were for car enthusiasts. Particularly for those with any awareness of foreign cars—for instance, the typical Road & Track reader. Newly enacted U.S. emissions and safety regulations choked the performance of cars sold here, while shrinking R&D budgets limited consumer choice as big manufacturers certified fewer models and engine families for sale. Meanwhile, several smaller foreign brands bowed out of the U.S. market entirely.

This story originally appeared in Volume 18 of Road & Track.

For many years, those who wished to partake in tasty automotive hardware sold elsewhere had three basic choices. They could (1) expend considerable effort and sums “federalizing” noncompliant cars from abroad, (2) emigrate, or (3) lump it.

Then, in 1988, came a quiet thunderbolt: the Imported Vehicle Safety Compliance Act, also known as the 25-year rule. An amendment to the National Traffic and Motor Vehicle Safety Act of 1966, it “exempts non-conforming foreign motor vehicles that are 25 years old or older (‘classic or antique’) from the restrictions imposed by this Act.” It was accompanied in due course by a maddeningly non-harmonizing regulatory amendment from the EPA that permitted the entry of non-emissions-compliant machinery at least 21 years old.

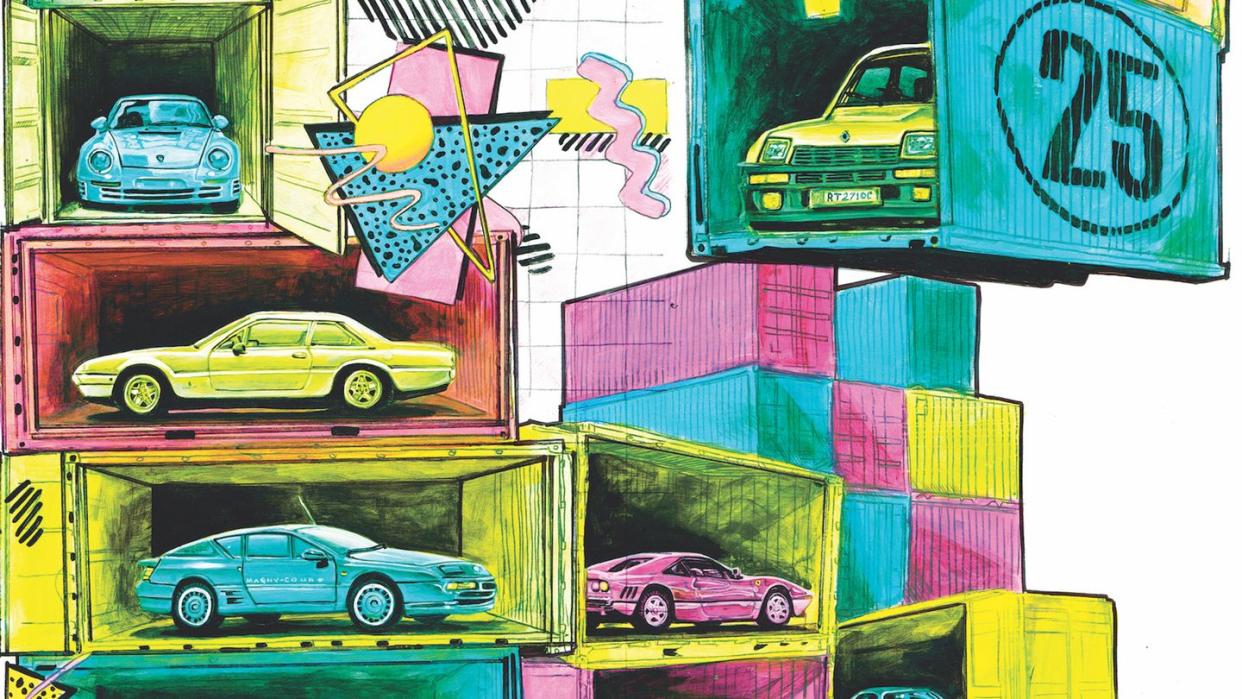

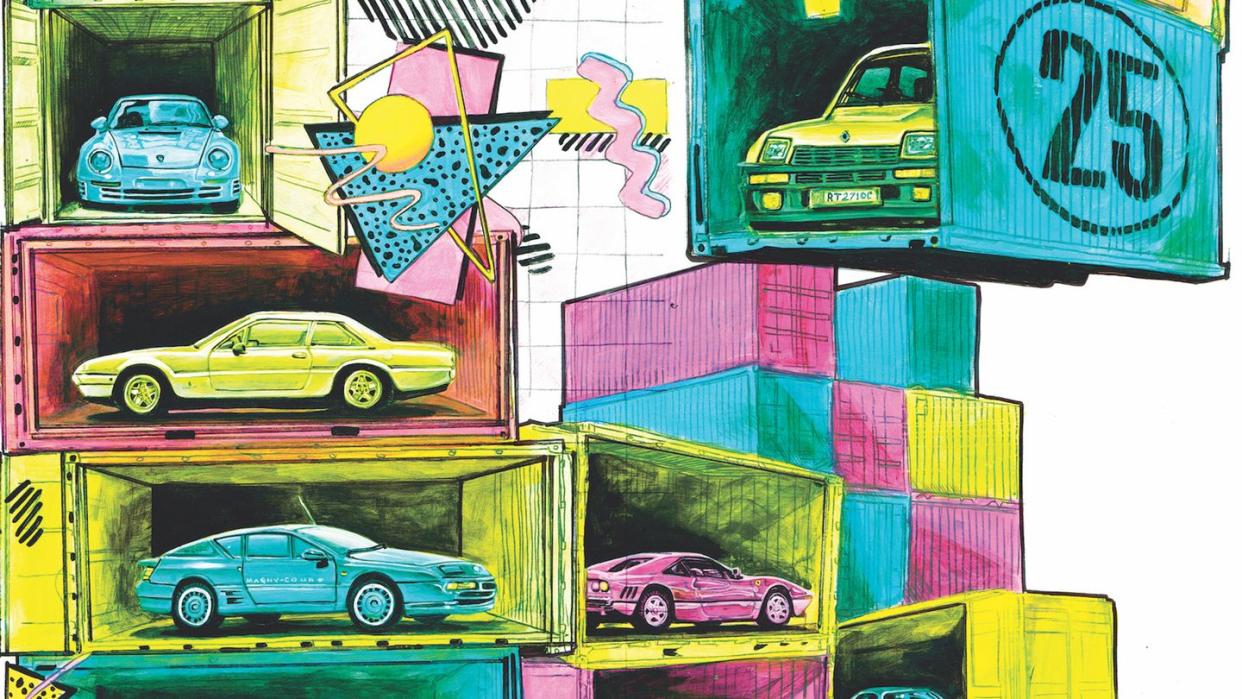

The effect of the rules would not be realized for some years, but beginning in the late Nineties, the amendment’s impact became apparent. Forbidden fruit—Alfa Romeo Montreals, late-model Fiat Dinos, MGB GT V8s from the early Seventies—could be imported to America for nothing more than the price of purchase, applicable duties, and shipping fees.

Today the rule’s ramifications are even clearer, as a recent visit to the docks at Port Newark in New Jersey (to pick up a 1997 Renault Twingo out of France) confirmed. The port was alive with the sights and sounds of exotic and oddball foreign cars. A steady stream of 25-year-old or older imports from Europe, Japan, South America, and elsewhere join us every day to make our roads a little more interesting.

On the day of our visit, old-school Land Rovers and first-generation Minis predominated, along with Japanese domestic-market offerings: right-hand-drive Land Cruisers, Nissan Patrols and Skylines, diminutive kei trucks, and micro–sports cars. We also spied a few formerly verboten Ferraris, a right-hand-drive Ford Escort RS, a Citroën CX, an MGF, and a Lancia Delta Integrale. Just another day at the docks—rare and desirable machines, all noncompliant when new, yet all now perfectly legal.

No discussion of the 25-year rule is complete without reference to the situation predating its adoption. Dick Fritz, an engineer working for the famous Ferrari importer and dealer Luigi Chinetti in the Sixties, became immersed in helping the chronically underfunded Italian sports-car maker meet then-new U.S. emissions and safety regulations. He left in 1976 to found AmeriSpec Corporation, one of the few outfits that enabled “gray market” machines (cars imported outside the manufacturers’ American sales arms) to meet federal emissions and safety standards. Others often fudged the numbers, an infraction that ultimately sent several rule breakers to jail. In the process, Fritz visited Washington often, helping the DOT and EPA devise procedures and protocols instructing would-be converters how to bring cars into compliance.

Aided by favorable exchange rates that made buying a high-end machine abroad a serious cost saver, Fritz notes that it “was a viable business because the European manufacturers were bringing in only a few models, and they were claiming that they couldn’t make [others] legal. Well, that wasn’t true. But by limiting models, whether it was a Mercedes or Porsche or BMW or whatever, it would make it much easier for them” because it minimized crash testing, emissions certifications, and inventory expense.

But the companies’ restrictive import policies backfired. In 1985, more than 60,000 gray-market cars landed on U.S. shores, a stiff uptick from the 1500 that arrived in 1980. A 2018 report in Autoweek noted that of those 1985 gray-market imports, more than 20,000 were Mercedes vehicles, representing an approximate $300 million loss in sales for the company’s American operation. Intense lobbying of Congress and state regulatory agencies, much of it spearheaded by Mercedes, followed, along with scare tactics in the form of talk about the legal and safety repercussions that might befall owners of such imports. Meanwhile, stricter enforcement of the compliance standards put almost every gray marketeer out of business.

In Fritz’s view, more than anything, the relative strengths of European currencies versus the dollar made compliance conversions less attractive. Along with increasingly consistent regulation and continuous improvement of engine management and emissions technology, manufacturers, mindful of their Eighties miscues, were able to expand their U.S. offerings. The gray-market business petered out, though Fritz takes pride in legally converting seven McLaren F1s and more than a few Porsche 959s, something Porsche said couldn’t be done.

A car-lover’s community for ultimate access & unrivaled experiences.JOIN NOW

Hearst Owned

Which brings us, finally, to the 25-year rule’s creator: Richard “Dick” Merritt, who worked in the National Highway Transportation Administration (NHTSA). Merritt, who died in 2021, was the rare gearhead walking the halls of the DOT. In 1968, along with Warren Fitzgerald and Jonathan Thompson, he penned the first serious Ferrari tome, Ferrari: The Sports and Gran Turismo Cars. A biblical volume in the eyes of many, it chronicled the output of the firm, then only 20 years old, and helped transform old Ferraris into something more than just used cars. Merritt assisted in founding the Ferrari Club of America and shepherded many an old Modena creation away from the junkyard, personally owning almost 50 examples over the course of his life. Many credit him with the marque’s explosive surge in value.

But of greater significance here, Merritt worked as a compliance officer for NHTSA for over three decades. He liked to say he was “the only bureaucrat that actually wants to help people.” And so he did. Merritt crafted the 25-year rule, cutting through the yards of red tape the DOT would ordinarily use to strangle enthusiast imports.

How’d he get away with it? Dave Kinney, publisher of Hagerty’s classic-car pricing guide, says: “The official line was the gray-market cars were less safe than U.S. spec. The real story may be that 25-year-old cars present no threat to new-car manufacturers.” Whatever the reason, enthusiasts’ debt to Merritt is enormous. As fans of foreign classics—like the R34 Nissan GT-R, legal for U.S. import in January of next year—we say respect is due.

You Might Also Like