Feds to Triangle: Don’t expect any federal money to build your commuter rail line

After years of planning a commuter rail system to link the Triangle’s largest cities and Research Triangle Park, local officials learned this spring that the federal government will not help pay for it.

Representatives of the Federal Transit Administration told a group of Triangle leaders that the COVID-19 pandemic has changed how people use transit and that trains that serve morning and evening commuters to central business districts have become outdated.

Instead, FTA officials said the government will provide money for cheaper and more flexible bus rapid transit systems like the ones Raleigh and Chapel Hill plan to build in the coming years, according to Raleigh Mayor Mary-Ann Baldwin.

“So we’re told, ‘This is what we’re going to fund, keep doing it,’” Baldwin said. “What we’re also told is, ‘We’re not funding commuter rail.’”

The meeting took place in Washington, D.C., in March. It was organized by Baldwin and Joe Milazzo, executive director of the Regional Transportation Alliance, a program of the Greater Raleigh Chamber of Commerce that calls itself the voice of the business community on transportation.

Also included were top county commissioners — Brenda Howerton in Durham and Shinica Thomas in Wake — and Sig Hutchinson, who heads the board of GoTriangle, the agency leading the commuter rail planning.

It’s not clear if any of the participants have previously spoken publicly about the meeting. But Baldwin mentioned it Friday at a gathering of hundreds of political, civic and business leaders organized by the Regional Transportation Alliance. The event’s theme: Bus rapid transit, or BRT, and how it can someday link the region.

Hutchinson told the gathering that the FTA will pay for half of qualifying BRT lines. He said federal officials like the lower cost of the bus-based systems and that they can more easily adapt to changes in commuting patterns, as a region grows and develops.

It’s too soon to say that the Triangle won’t ever have a rail-based transit system, Hutchinson said afterward.

“But there’s only so much money,” he said in an interview. “So what I want to do is focus on where the energy is, and right now the energy is on bus rapid transit. And the federal government is 100% supportive of it and will pay for half of it.”

Construction of first BRT line to begin this fall

Bus rapid transit combines the lower cost and flexibility of buses with some attributes of rail, including covered, elevated platforms, priority signals at intersections and dedicated lanes to avoid traffic. Because of those similarities, Milazzo says BRT should stand for “Buses Resembling Trains.”

The Wake Transit Plan approved by voters in 2016 calls for building four BRT lines radiating out from downtown Raleigh. Construction on the first line along New Bern Avenue east to a park-and-ride lot on New Hope Road is expected to begin by the end of the year, said Het Patel, the city’s transit planning supervisor.

Next up is the southern leg, from downtown along South Wilmington Street to Garner Station Boulevard and the Walmart Supercenter on Rupert Road, followed by the western route to downtown Cary and a northern one to North Hills and/or Triangle Town Center.

Meanwhile, Chapel Hill Transit hopes to begin construction in 2026 on an 8.2-mile BRT line between Eubanks Road, UNC Hospitals and Southern Village.

The RTA used Friday’s gathering to announce a new study, in conjunction with the N.C. Department of Transportation, on how to extend and link the planned BRT lines across the region. The Freeway and Street-based Transit study — or FAST — will build off an earlier one and look at particular roads that could be modified in ways to help buses move more quickly.

One goal of the 12-month study, which kicks off this fall, will be to identify a way to extend a BRT line to Raleigh-Durham International Airport.

Because of cost and logistics, there were never plans to extend a commuter rail line to RDU, even though going to the airport is one time many area residents can envision themselves riding transit. On weekdays between 6:30 a.m. and 6 p.m., GoTriangle operates a shuttle between the airport and its regional transit center near RTP, where riders must transfer to another bus. At nights and on weekends GoTriangle Route 100, an express bus that runs between the regional transit center near RTP and downtown Raleigh, stops at the airport.

A BRT line could entice more riders by being faster and more convenient. Speaking at the RTA event, RDU’s chief development officer, Bill Sandifer, acknowledged that the airport has not focused on transit connections to the community as much as it should.

“We need to be more engaged. Because BRT needs to come to the airport,” Sandifer said. “BRT needs to be a fundamental solution to how we get not only customers but employees to and from the airport.”

Little progress on commuter rail

This spring and summer were supposed to be when local governments in Durham, Wake and Johnston counties decided whether to begin developing a commuter rail system in earnest. They were to base their decision on a feasibility study that GoTriangle completed for the system last winter.

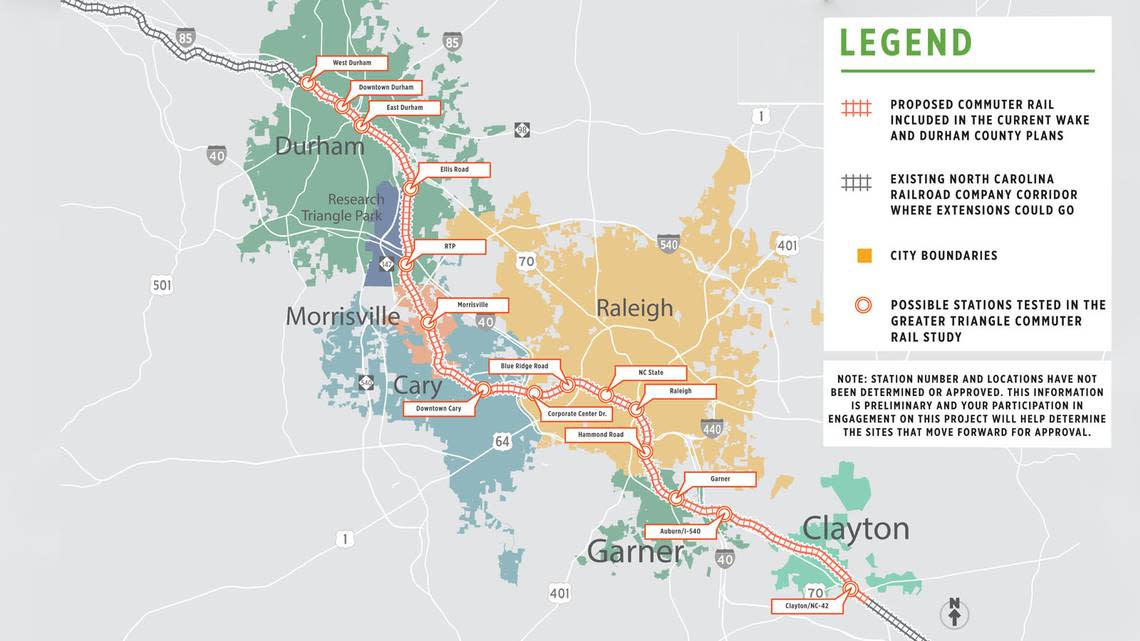

The study described a $3.2 billion, 43-mile commuter rail line between West Durham and Clayton, with stops at 15 stations, including RTP and the Amtrak stations in downtown Durham, Cary and Raleigh. The agency sought feedback from the public online and at a series of open houses in January and February.

The system’s cost made it unlikely to qualify for a federal program that pays 50% toward constructing new transit systems. Local transit taxes in Durham and Wake counties wouldn’t generate enough money to cover the local share, so GoTriangle suggested the system be built in stages. Deciding which segments to build first was one of the challenges facing local governments.

The two regional organizations that do transportation planning for the Triangle each appointed subcommittees to review the feasibility study but have not made any recommendations.

The commuter rail proposal is the third attempt to develop a regional transit line that runs on rails. In 2019, GoTriangle gave up on a proposed 18-mile light rail line between Durham and Chapel Hill, after the FTA said the project was unlikely to qualify for federal funding because of rising costs and uncertainty over acquiring the needed right-of-way.

Before that, GoTriangle’s predecessor, the Triangle Transit Authority, spent years planning a similar commuter rail system between Durham and Raleigh. That idea was abandoned in 2006 after failing to win federal support or funding.