How the Fed weighs 'political risk' behind closed doors

Jay Powell said this past week that pending elections don't get discussed at Federal Reserve meetings, challenging reporters to read the transcripts for themselves.

"I can't say it enough: We just don't go down that road," the Fed chair told reporters Wednesday afternoon when asked if the bar was higher for making rate changes close to an election.

And he offered a challenge: "You can go back and read the transcripts," he said. "See if anybody mentions, in any way, the pending election."

What Yahoo Finance found after reviewing years of Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) meeting transcripts was — as Powell promised — few overt mentions of coming elections and no debate on the political merits of any one candidate over another.

But political topics still came up repeatedly as Fed officials wrestled with decisions that affected the US economy.

The transcripts show central bank policymakers weighing both the possible economic impacts of political events — including elections and the coming of a new president — as well as the potential political reaction to their decisions.

In just one example, Minneapolis Fed president Neel Kashkari took time in a January 2018 meeting to highlight these pressures as then-Chair Janet Yellen was set to depart and Powell was preparing to take his current seat at the head of the table.

"We work very hard, all of us, to be nonpolitical and nonpartisan, and yet we exist in a partisan, political world," Kashkari said in the transcript of that gathering. He praised Yellen, saying she had effectively "navigated that tension."

Throughout the seven meetings that Powell went on to chair in 2018, as one example, the term "political" was uttered 40 times, according to a search of the transcripts.

It came up as committee members discussed everything from then-President Trump's trade policy to developments in Europe to the economic effects of "political tensions in the United States" around that election year.

Read more: How much control does the president have over the Fed and interest rates?

This consideration of these political risks is common, and it's a topic Federal Reserve historian Sarah Binder says she has seen again and again in her reviews of transcripts. Political debates are especially front and center, she says, around fraught topics like setting an inflation target and the Fed's balance sheet.

"The fact that numerous Fed officials are mentioning politics in FOMC meetings suggests that such considerations are at least part of the mix of forces that ultimately shape the Fed's statement and policy choices," she wrote in a note to Yahoo Finance.

The publicly available transcripts cover Powell's tenure from 2012, when he became a Fed governor, to his first year as chair in 2018. Transcripts are released on a five-year delay, so recent meetings are not yet publicly available.

The politics of interest rates

While politics and elections don't appear to come up often in conversations around interest rates in recent history, they're far from absent entirely.

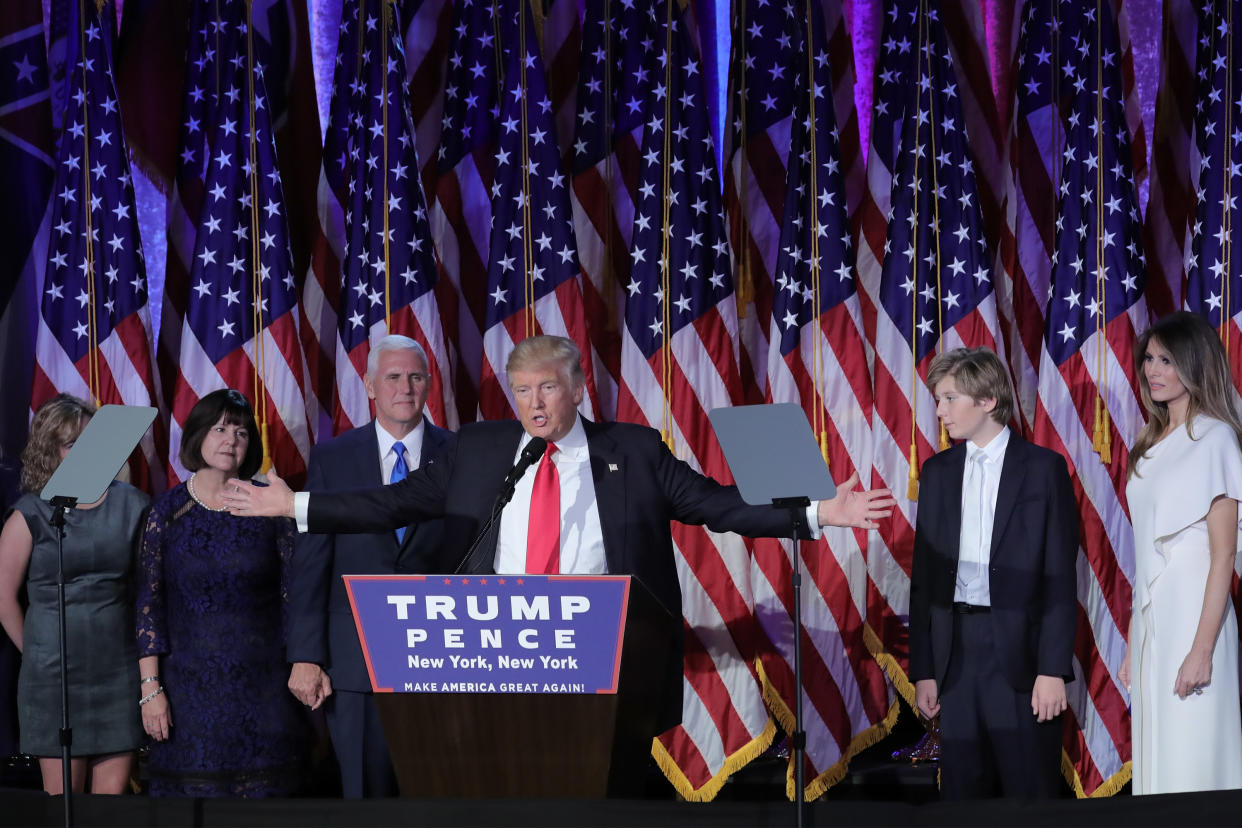

Discussions of the election and its possible economic impacts came up during meetings throughout 2016, before and after that year's historic election between Donald Trump and Hillary Clinton.

Eric Rosengren, the then-president of the Federal Reserve Bank of Boston, weighed in on the topic in a June 2016 meeting when he discussed both the US election and another political movement that year to withdraw the United Kingdom from the European Union.

"Our own election is viewed by many as far riskier than the Brexit vote," he noted at the time, adding a concern that the uncertainty around the US election specifically "might make us reluctant to move in September."

In the end, the Federal Reserve did hold steady on interest rates through the election, waiting until December 2016 before raising them. It was a decision that Yellen said at the time reflected the economic progress over the course of 2016. Under questioning from reporters she added of the recent Trump win that "all the FOMC participants recognize that there is considerable uncertainty about how economic policies may change."

Rosengren, asked Thursday in a Yahoo Finance appearance about his 2016 comments, noted that the Fed monitors elections because they "have an impact on the economy and an impact on asset prices."

He added that in the cases of 2016 and 2020 (as well as likely to come in 2024), a close election can be a significant source of economic uncertainty because "the two choices have quite different implications for policy."

Another Fed official who touched on the topic in 2016 was Stanley Fischer, then the vice chairman of the Board of Governors.

"As we look to our December decision, we will be navigating treacherous waters," he said during a November 2016 meeting, just days before voters went to the polls. Fischer added the coming decision "should reflect our expectations of the nonmonetary economic policies that will be followed in 2017 and later."

It was an apparent reference to fiscal policy changes that could be in the offing under a new president.

"Are we, therefore, going to be making decisions that reflect our political preferences? Absolutely not," he added. "I'm confident we'll continue to follow that principle, as is both our legal obligation and our standard practice."

'Donald Trump has won the presidency'

During the December FOMC gathering in 2016, there was some conversation about the consequences of Trump's surprise victory.

Like millions in America and around the world, committee members were trying to assess what to expect in the years ahead from then-President-elect Trump.

"Let's take stock: The Chicago Cubs have won the World Series, Donald Trump has won the presidency, and Bob Dylan has won a Nobel Prize," James Bullard, the St. Louis Fed president at the time, joked, according to the transcript.

Fischer also returned to the topic, assessing the reaction to Trump's win.

"Market reactions since the election victory of Mr. Trump have been remarkably positive and consistent with our moving at this meeting," he said of the interest rate increase implemented that week.

It was the committee's first and only increase that year.

The political conversations in 2016 were considerably milder than was common in decades prior, according to academics who say Fed transcripts from the 1970s through the 1990s demonstrate that politics often played a more direct role.

A study based largely on Fed transcripts from the 1970s even concluded that fears of political blowback negatively influenced the central bank's reaction to inflation during that era.

Thomas Drechsel, an assistant economics professor at the University of Maryland, said part of the reason for less political talk in recent years is the committee members know their words will eventually be seen now that all transcripts are made public with five-year lags.

"Since 1994 the committee operates with the understanding that its transcripts are released to the public, so they are careful not to bring this up," he said in a note to Yahoo Finance, adding that it didn't necessarily mean these political factors were something the committee members didn't "worry about."

Inflation targeting and the Fed's balance sheet

While Fed members might avoid linking politics and interest rates too overtly, the connection can be more direct on other topics.

The Fed 2% inflation target has been a source of political discontent for decades, mostly from politicians on the left who want more of the focus on unemployment.

Professor Binder has documented politically tinged conversations around that inflation target as far back as 1995 under then-Chairman Alan Greenspan. And it's been referenced at least once during Powell's time in office.

"I don't think the public will support us raising the inflation target," said Kashkari during a meeting in the summer of 2018.

He noted the strong opinions on both sides of the issue about which approach is best for the economy but added that either way, the political landscape likely necessitated no change in policy.

"I am cognizant of the political reality," he added. "At the end of the day, the public has to support us in whatever we choose to do."

Politics was also discussed again and again as a factor in the Fed's balance sheet debates of 2018.

The level of assets the central bank holds is a controversial topic for some lawmakers — and was a campaign trail issue for some in that year's midterm elections.

It remains an issue today, with one bill currently under consideration on Capitol Hill that would mandate a balance sheet unwinding and require it to remain at or below 10% of US GDP.

The politics of the balance sheet came up repeatedly in the transcripts of Fed meetings in 2018 on July 31-Aug. 1 as well as following that year's midterm elections on Nov. 7-8.

"We may run into constraints, both political and operational," Cleveland Fed president Loretta Mester noted of any moves.

"Our use of the balance sheet does put our political capital significantly at risk," added Richmond Fed president Tom Barkin.

"Federal Reserve independence is critical, but there's no doubt that we're going to need political support for our actions in the next downturn, particularly if it involves using the balance sheet," added Randal Quarles, the Fed's vice chair for supervision at the time.

The value of assets on the Fed's balance sheet declined gradually throughout 2018 and into the first half of 2019 before beginning to rise again that fall. The balance then jumped significantly in early 2020 as a part of the central bank's response to the COVID-19 pandemic.

Powell announced just this week that the Fed would slow its pace for reducing the balance sheet size in the coming months.

The Fed's 'nonchalance'

It's clear from the transcripts that Fed officials were wrestling with the challenges of setting economic policy amid the heated political context of Washington, D.C.

Sometimes, committee members offered wry commentary on their mission of staying independent even when politics is often unavoidable.

In one lighter example from September 2016, the members noted how a meeting four years hence was set for Nov. 4-5, 2020 — just one day after that year's presidential election.

After a short debate about adjusting the date and an agreement that the economic calendar made that unadvisable, they agreed to keep the schedule as is.

One upside, quipped then-Richmond Fed president Jeffrey Lacker, was that the central bankers coming together while votes were still being counted "does demonstrate our nonchalance."

Ben Werschkul is Washington correspondent for Yahoo Finance.

Click here for politics news related to business and money

Read the latest financial and business news from Yahoo Finance