My Father-in-Law Had the Whole Family Select His Final Resting Place Before He Passed

From The Georgia Review

I. The Cabin

Jerry McGahan was not well when he stepped out of his Montana cabin on a gusty mid-September afternoon in 2016. His hair was wiry and white. Steroids had swollen his face, rounding the usual angles of his jaw. He elbowed open the front door and slowly crossed the porch. His feet had memorized the distance.

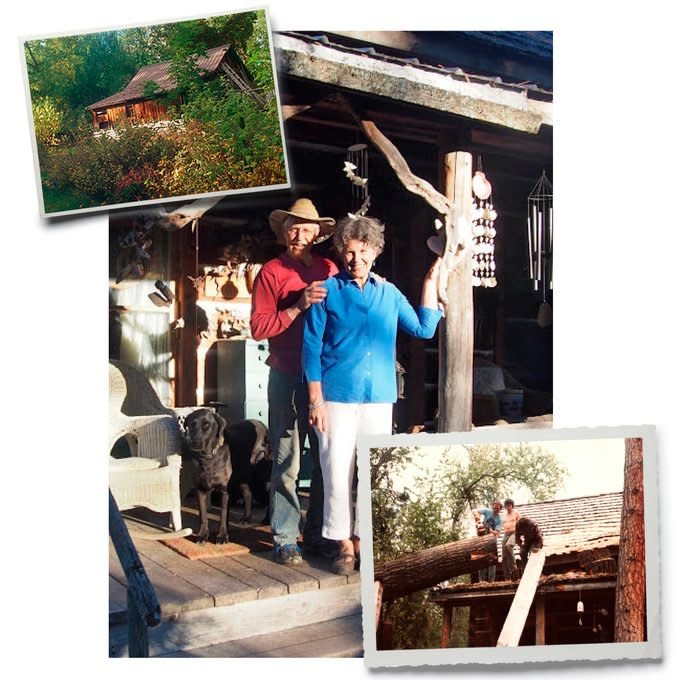

The cabin was older than he was, but solid. In 1973, he found it for sale at the foot of the Mission Mountains just north of here. He paid $300 for it and gathered some friends to help take it apart. Jerry numbered the logs, loaded them onto a truck, and reassembled them along the Jocko River with his first wife, Libby. Using skills he learned from carpentry books and an eighth-grade shop class, he framed the windows, wired the outlets, plumbed the pipes, and built the cabinets. By the end of the summer, it became a home in this sylvan oasis.

The cabin and the surrounding gardens have a way of arresting people. Those who come down the driveway, whether the mail carrier or—once—the poet Allen Ginsberg, know they are seeing something rare and beautiful, the fruits of an autonomous life. When a hospice doctor visited, he stepped out of his car, swept his gaze over the house, the mossy rock gardens, and the corkscrew hazel out front, and said, “It looks like a hobbit lives here.”

This is where I first met Jerry on a cloudless spring morning in 2007, shortly after I had fallen in love with his daughter in Missoula. Hilly first described her father to me as a writer and beekeeper who never ate fruit out of season, refused to own a cell phone, bought almost nothing, and knew a lot about birds. In person, I found him to be self-possessed and encyclopedic but simultaneously humble. He listened more than he taught.

Hilly and I married in 2012, in the shade of trees Jerry planted behind the cabin. When Jerry was diagnosed with prostate cancer in 2014, Hilly was pregnant with our first son. The cancer was the type that could have been removed if Jerry had gone in sooner, but he thought of doctors the way he thought of mechanics: The more you saw them, the more they found to fix. His lifestyle of homegrown food and manual labor imbued him with the immortality of a tree, for which death is possible but implausible. Jerry never scheduled the checkup that could have sounded the alarm, and his truancy came with a price: By the time a doctor found it, the cancer was aggressive and inoperable. His oncologist said he might have months to live. Almost three years passed.

On that September day as he stepped out of his house, Janet, his second wife for 35 years, took his arm. Her body was riddled with disease too. A third round of breast cancer had metastasized to her bones. Until recently, they scheduled oncology appointments together the way they once went to the movies. For a while, they were racing in lockstep toward the end. Now it looked as though Jerry would finish first.

But before then, he had one bit of business left to attend to in the orchard, one final decision to make before the cancer pulled the rafters down around him. So, with all six of his children and some grandchildren alongside, Jerry slowly stepped down from the porch and started walking.

II. The Birds

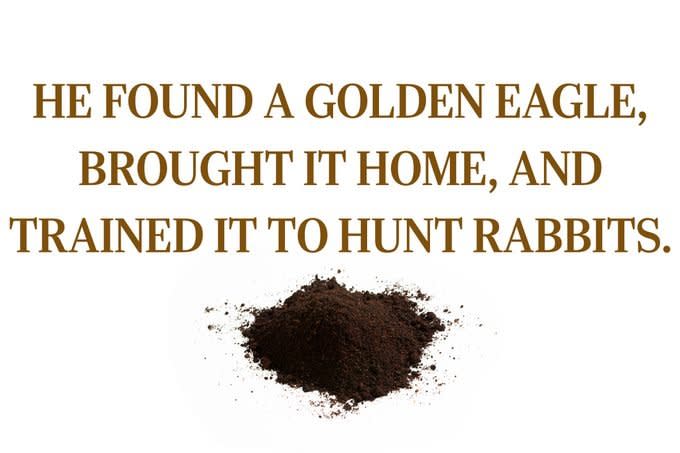

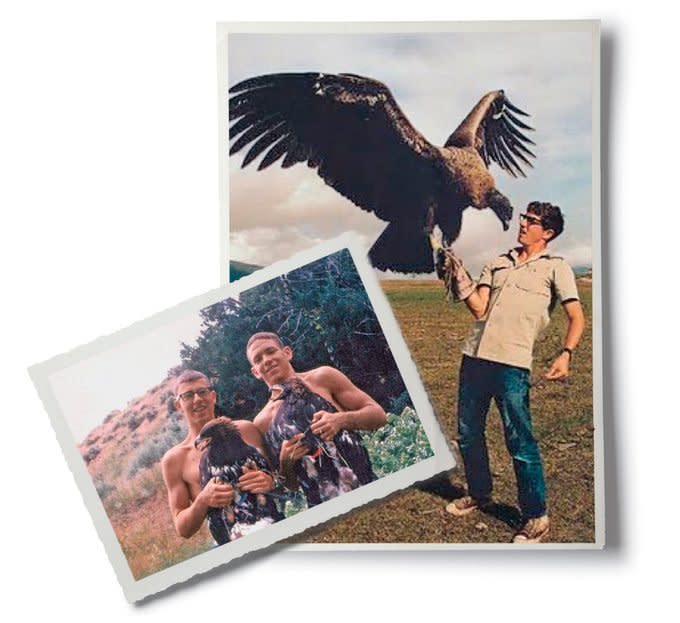

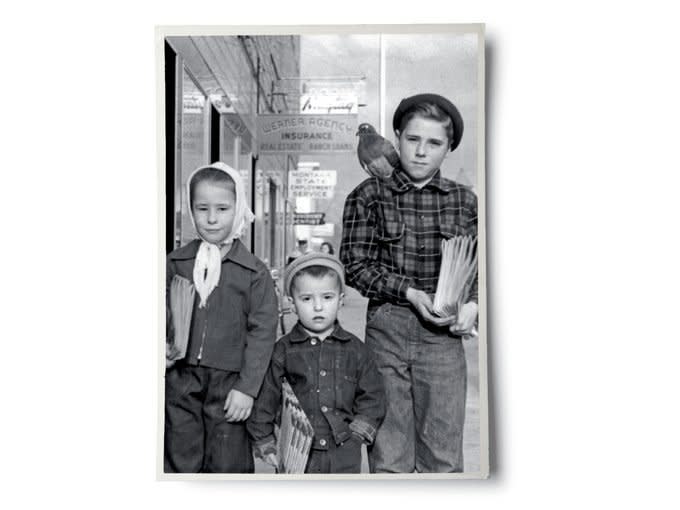

Jerry McGahan was born in the winter of 1943 and grew up in Livingston, at the mouth of Montana’s Paradise Valley. He was a scrawny, awkward boy with freckles and few friends, so he learned to entertain himself. Once, he found a baby pigeon, which he brought home and named Sapphire. The bird became his companion, riding on his cap when he delivered the Park County News. J erry soon became infatuated with birds. One day in high school, he found a fledgling golden eagle in a nest on a cliff outside of town. He brought it home and named it Torrey. She lived in a large cage outside his house and ate prairie dogs that Jerry stored in the freezer. On the weekends, he trained her to hunt rabbits. When Jerry went to the University of Montana in Missoula in 1961, he brought Torrey with him. She lived in an enclosure behind the gym, and between classes Jerry would fly her on the mountain behind campus.

At UM, Jerry compiled his fastidious field research into a paper about the hunting habits of golden eagles. It’s still one of the most complete studies on eagles in Montana. And he met Libby, a liberal arts major from Missoula who liked to hike as much as he did. They married in 1966, the same year Jerry finished his master’s in wildlife biology at UM. Then he and Libby moved to Madison, where Jerry got a doctorate in zoology at the University of Wisconsin. As part of his graduate research, he received a grant from the National Geographic Society to study Andean condors in South America. Jerry filmed a documentary and wrote a story for the May 1971 issue of National Geographic. Libby took the pictures, including the cover photograph of Jerry with a giant Andean condor perched on his arm, almost ten feet worth of wings flared, seemingly ready to peck off Jerry’s nose. Jerry named that condor Gronk and brought it home with him to Montana in 1973 before donating it to a zoo.

Jerry and Libby settled on a piece of cattle-trod land in Arlee that to him was ripe with potential. They had adopted their first child in Colombia and had named him Jay. In 1974, they had a daughter named Jordan. With a new family to provide for, Jerry bought a flatbed pickup, built some hives, and started a honey business that he called Old World Honey. After Jerry and Libby divorced, Jerry married Janet, who had two sons, Simon and Duncan. Together Janet and Jerry had two more daughters, Romy and Hilly. They were both born in the cabin, within earshot of the Jocko River, and, like their siblings, grew up weeding the gardens and pulling honey alongside their father.

Because Jerry spent so much time outside, beekeeping, gardening, or just walking, birds still inhabited his days. One morning in 2010, he walked out of the cabin and heard a song he didn’t recognize. He found the bird in a bush and went back inside to consult his field guide. It was a Carolina wren. He reported it to the wildlife department at the University of Montana, but they were skeptical; the Carolina wren is common in the East but had never been seen in Montana. Until then.

III. The Dirt

From the moment he began living along the Jocko River, Jerry cultivated a sense of belonging to the place. He filled it with trees, flowers, and vegetables. He spent so much time working it that its geography became a sort of map of himself. To dispose of garbage—old kitchen timers, the children’s trophies, and other refuse—he put piles of the stuff in the yard and covered it all with big, naturally sculpted, lichened rocks that he and Janet quarried in the mountains. Then he filled in the gaps with soil and planted flowers. If you cared about the man, you cared about his flowers, and given the opportunity, he’d introduce you to them. Like the birds, they were among his closest friends.

As were the trees. In total, Jerry planted 54 apple trees here. He began soon after he arrived. First, he planted the rootstock. He waited a year for it to sprout, then drove to experimental orchards to taste their apples. The next spring, he returned to cut wood from the varieties he liked and grafted that onto his young trees. Slowly the rootstock and the grafts matured into trees, and after a decade or so, Jerry picked his first apples.

They were wonderful, unusual apples, with names such as Incarnation, Star Song, and Priscilla. He had Sansa apples from Japan and an English variety called Ashmead’s Kernel that originated in the 18th century. One apple called New Jersey 46 has soft pink flesh that tastes like strawberry soda.

Jerry then crossed his favorite varieties, hoping to combine one apple’s flavor with another’s texture, for example, or its storability. After four decades, Jerry’s trees contained 175 kinds of apples—82 standard varieties and 93 of his own crosses. His favorite cross, between a Sweet Sixteen and a Gold Rush, had a clean crunch and tasted faintly of fennel. Jerry called it the Jocko.

Late in Jerry’s life, I learned that he never actually ate his apples. He’d take a bite now and then to feel the texture and enjoy the flavor, but he spat out the pulp. He made sure every last one of them was picked at peak ripeness and distributed to friends, family, or the food bank. To me, the utility of an orchard was its fruit, but to Jerry an orchard was a laboratory in which every apple was an incubator for its seeds. The fruit would ripen and rot in a season. But the seeds? They were eternal.

On that September afternoon, we all filed into the grassy orchard, where Jerry pointed out a limb of Jocko apples. They weren’t ready yet, but we hadn’t come to eat. Instead, we watched as Jerry swiveled his torso around the orchard, looking for something. Wind whistled through the tops of the pines as Jerry clutched his morphine pump in his left hand.

“What about this spot here?” he finally asked. “You like this end? I kind of like this end too. You come in the gate, and you have this spot to go to. You have to walk.”

He walked over to the spot and scanned the ground.

“If it were camp, I’d kinda like my head to go here,” he said, pointing to the earth. Duncan, his 42-year-old stepson, set a large rock on the ground.

“My sleeping bag would come down this way,” Jerry said. “Hey, Dunc, move that rock two inches to the left.”

Jerry was looking down now, making small measuring steps, as if he were about to dive into water. Then he got on his hands and knees, turned, and flattened his back against the earth. His palms lay flat on the grass, his head rested on the rock like a pillow, and his pain pump whirred beside him.

“How do you like it, everybody?” he asked. “OK?”

It wasn’t OK. Not to any of us, no matter how long we’d known it was coming. Death for Jerry was still inconceivable, oxymoronic even. But if this man had to be confined to a single patch of soil, no spot was more fitting than this. Duncan gently sank a shovel into the grass on either side of Jerry’s head and again at his feet, upturning four divots of sod.

No one talked. We were all staring at our feet and this plot of grass beneath an apple tree, next to a garden hose; this ordinary piece of dirt that death would sanctify. We stood there, awkward under the uncertain certainty of it all. Jerry read the mood and did the kindest thing he could. He walked over to a tree and shook a limb so that ripe Noreen plums rained down on us. It felt as if he’d shaken us too. Soon we were all stooping down to pick them up. The flesh was bright red and juicy. Janet walked over to her husband and wrapped her arms around his waist.

“A graveyard and an orchard,” Jerry said. “They go well together.”

IV. The Hole

With this decision made and his energy waning, Jerry turned back toward the house. As we walked down the driveway, some of his older grandchildren and one great-grandchild were already returning to the orchard with shovels. No one knew how much time we had, but it seemed sensible to dig the hole before the ground froze.

In the end, more than a dozen family members dug the hole. The job took several days. The physicality of the labor and the simplicity of the objective were a refreshing escape from the anguish unfolding in the cabin. After one spell of digging, I returned to the house sweating and Jerry looked up at me from his pink recliner with soft eyes. “Thank you,” he said quietly.

Meanwhile, Simon and Duncan built a box. They scavenged scraps of wood from the Honey House—the old sides of Jerry’s honey truck, pieces of his beehives, and the remains of an old sign Janet had painted for a local café. The sign became the lid of the casket. Inside, the boards read SOUP & SALAD, ESPRESSO, BREAKFAST. The casket sat outside on the porch, a thing of beauty, with handles of purple-grained juniper and a soft, sanded surface. Our two-year-old son, Theo, and his three-year-old cousin, Selah, would bang on it gleefully, as if it were a drum.

In the midst of these preparations also came new beginnings. One afternoon, Jerry’s daughter Romy gave birth to a daughter, Opal. Duncan drove Jerry into Missoula to see her, arriving just minutes after she was born. Jerry looked gaunt and exhausted, but his face glowed several watts brighter when he sat down and cradled his newest granddaughter.

“You look handsome holding that baby,” Janet told him.

His dry lips smiled. “It’s just reflected light,” he said.

V. The End

Eventually, we moved him from the bedroom upstairs to a hospital bed in the living room. Janet oriented it to face the window and the flaming-red sugar maple outside. The room, like the rest of the house, was filled with curiosities Jerry and Janet had collected. There was a handmade violin from Mexico’s Copper Canyon, a whale vertebra they’d found on a beach, an obsidian hunting knife, a pot punctured by the teeth of a grizzly. The house hummed with stories.

Hospice sent out waves of nurses, pharmacists, and social workers—even a massage therapist and a harpist. The nurses steadily increased the dosage of the pain pump. In the evenings, when the nurses had gone, Janet climbed into bed with him and they ate ice cream and watched Trevor Noah. I was in the room on one of these evenings, sitting on the sofa. I watched Jerry look over at Janet, his companion of 35 years, the patient, gregarious artist, the right brain to his left. “Let me hold your hand,” Jerry said. “Just to hold it, I guess.”

We held vigil over his bed, shuffling seats around him, ceding chairs to our superiors in the hierarchy of closeness. The grandchildren entertained themselves outside, throwing leaves at each other. Duncan’s wife, Jana, sang Norah Jones. For long stretches, Hilly sat at the old saloon piano and played.

Jerry’s eyes brightened with the music. “Wow,” he whispered. “Wow.” They were his final words.

A hospice nurse came to pronounce the death. Looking tired but stoic, Janet brought down fresh clothes: his best pair of dark Levi’s, a rust-colored corduroy shirt, a vest, and his sun hat. We washed and dressed him, wrestling his stiffening arms through the sleeves.

When we laid him on a bed of sugar maple leaves inside the casket, I noticed his expression had somehow shifted. He’d looked chagrined when we washed him and contemplative when we dressed him. Now a faint smile had crept into his lips. He looked peaceful and a little bemused, maybe even proud.

Janet knew he shouldn’t go into the earth alone. She put a bottle of his home brew into the box, a pair of his hand-dipped beeswax candles, and a stack of their old love letters. His hunting partner, David Rockwell, put in a raven’s skull and a bison hoof. Jay Sumner, Jerry’s best friend from childhood, contributed a crumpled dollar bill, a miniature cribbage board, and the game’s best hand: three fives and a jack. Hilly picked a ripe Jocko apple and set it into her father’s palm. Some grandchildren arranged a bouquet of purple asters on his chest. Janet bundled his decades-old duct-taped parka under his head as a pillow. The casket was now a kind of message-in-a-bottle, a testament to the future of who this man was and what he loved.

“Some of the best things in life are in that box,” David said.

We walked with Jerry to the orchard one last time and slowly lowered him into the earth. Duncan said a prayer. Jana sang a song. Swarms of woolly blue aphids hovered in the air like electric-blue storm clouds. Then, under a gray sky, everyone began filling in the hole, and the most alive person I’ve ever known disappeared into the dirt. Even his trees seemed to kneel.

The following spring, when the crocus bulbs were poking out of the soil again as if by magic, almost-three-year-old Theo asked Hilly and me, “Where’s Grandpa?”

We were out in Arlee visiting Janet, and just then we were driving past the orchard. Hilly said, “Well, his body’s in the ground, right there.”

“But not his face?” asked Theo.

“No, his face too,” Hilly said. “His whole body.”

After a moment, I said, “I guess the answer is that we don’t know where Grandpa Jerry is. His body is in the ground, but some people believe we have souls and that when we die our bodies stay on earth but our souls go up to heaven.”

“Or they become a mountain,” said Hilly.

“Yeah,” I said, “or they live in that person’s favorite places.”

Theo considered this. Then he said, “I think he’s an apple.”

Inspiring Stories from People Who Found Their True Calling Halfway Through Life

This Teacher Saved a Grandmother's Life Thanks to Virtual School at Home

40 Years After Falling for a Girl, He Finally Got to Be with Her

The post My Father-in-Law Had the Whole Family Select His Final Resting Place Before He Passed appeared first on Reader's Digest.