Fate of Missouri prisoner Lamar Johnson in hands of judge. Prosecutors say he’s innocent

A week-long hearing that could lead to the exoneration of a St. Louis man, who local prosecutors say has spent 28 years in prison for a murder he did not commit, concluded Friday afternoon.

The fate of Lamar Johnson — who, at 49, has spent more than half of his life in prison — is now in the hands of St. Louis Circuit Judge David Mason, who presided over the hearing that started Monday.

Throughout the week, St. Louis prosecutors sought to prove Johnson is innocent of the 1994 killing of 25-year-old Marcus Boyd, for which he remains behind bars. They called to the stand several witnesses, including a key eyewitness who recanted and a convicted killer who says he and another man, not Johnson, killed Boyd.

Circuit Attorney Kim Gardner became convinced of Johnson’s innocence in 2019, but she did not have an avenue to release him. She then sought his freedom under a state law that went into effect in 2021 that allows prosecutors to petition a court to exonerate prisoners they have determined were wrongly convicted.

The law gave Jackson County prosecutors a path to free Kevin Strickland, a Kansas City man who spent 42 years in prison for a triple murder he did not commit. He remains the only person exonerated under the law.

The Missouri Attorney General’s Office argued that Johnson was rightfully convicted and opposed his release, like it has in nearly every innocence claim to come before it in the last two decades. Miranda Loesch, a lawyer for the AG’s office, said the testimony that led to Johnson’s conviction was “accurate.”

Then 21, Johnson was convicted in 1995 of first-degree murder in the Oct. 30, 1994, nighttime shooting of Boyd, who was found on the porch of a brick home in St. Louis’ Dutchtown neighborhood. Johnson was sentenced to life in prison without the possibility of parole.

At the urging of Johnson’s lawyers, Gardner’s conviction integrity unit in 2018 started reviewing his case. The next year, she released a report detailing how her office determined Johnson “had nothing to do with Boyd’s murder.” Her office found unconstitutional police practices and “serious prosecutorial misconduct” throughout his case.

For more than two decades, Gardner’s office said, Johnson’s co-defendant, Phillip Campbell, and another man, James Howard, credibly confessed to shooting Boyd alone and provided a motive. Campbell, who pleaded guilty after Johnson was convicted, got a seven-year sentence. Howard, who was never charged in Boyd’s killing, is now in prison for a murder he committed three years later, in 1997.

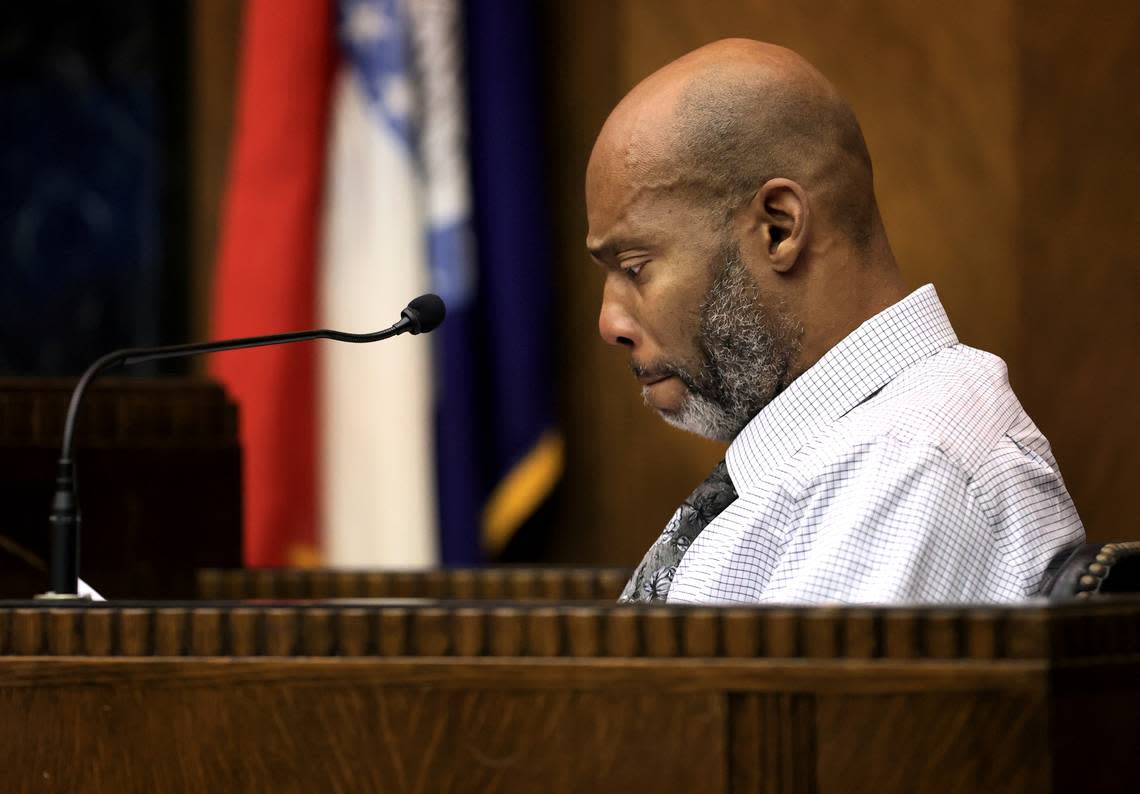

Howard took the stand Monday, again admitting that he and Campbell, who is now deceased, killed Boyd that fateful night. Howard testified he came forward because he was “trying to right” his wrongs, which included Johnson sitting in prison for his crimes.

“I didn’t think they would convict him because s—, he didn’t have nothing to do with it,” Howard testified.

Greg Elking, a star witness who identified Johnson at trial, testified he felt pressured and “bullied” by a homicide detective to name Johnson in the shooting — even though he could not pick out the killers, who wore black masks. His testimony that helped send Johnson to prison has haunted him, he said.

“I hate it, and I’ve been living with it for ... years,” said Elking, whose words caused tears to roll down Johnson’s face. “I just wish I could change time.”

Then-assistant Circuit Attorney Dwight Warren, who prosecuted Johnson, told the judge that without Elking’s testimony, he would not have brought the case against Johnson in the first place.

“I didn’t have any evidence,” Warren said.

Elking identified Johnson because his eyes looked like those of one of the shooters, according to police reports.

On Friday, the judge had Johnson stand in the courtroom while former St. Louis police detective Joseph Nickerson, who investigated the case, was on the stand. Mason asked Nickerson “what in the world” was distinctive about Johnson’s eyes compared to “pretty much any Black man” of a similar complexion.

Nickerson said one of Johnson’s eyes is slower than the other. Mason, who appeared skeptical of the response, asked that a photograph be taken of Johnson’s eyes so he can take a closer look later.

“You understand this man was convicted with what you just said?” Mason asked.

Nickerson did, but said Johnson also matched the age, weight and height of one of the suspected gunmen. Mason responded that a spectator in the courtroom did, too, and asked: “You want to arrest him as well?”

“I mean, really; you know that’s not that much,” the judge said.

In another dramatic moment this week, Mason became highly frustrated with Loesch, one of the AG’s lawyers, while Nickerson was on the stand.

Nickerson said Elking could not initially identify anyone after three viewings of a police lineup, which the former detective said was spelled out in a report. Loesch handed the judge a report when he asked for it, but Mason said that information was not in there and threatened to kick Nickerson out of the witness box.

“You going to shoot me straight, counselor?” Mason asked Loesch, accusing her of dancing around his questions.

Earlier this year, a Star report detailed how the questionable testimony of another man — a repeat jailhouse informant who has been described as a racist with a swastika tattoo — also helped prosecutors convict Johnson, who is Black. The informant, who was white, claimed to have heard Johnson confess to the killing while in jail, but his story, Gardner’s office determined more than two decades later, “was and is not credible.”

Loesch on Monday acknowledged that the informant, William Mock, was the “epitome” of a jailhouse snitch with a criminal history. But she said the case against Johnson did not “entirely” rest on Mock, who died in 2000.

At the beginning of the evidentiary hearing, lawyer Charles Weiss, who was serving as a special assistant to the Circuit Attorney, noted that the proceeding was a “rather historic moment” in the courthouse.

“This is the first time in the history of the 22nd Judicial Circuit where the court is hearing an actual innocence claim filed by a prosecuting attorney,” he said.

Judge Mason — who at one point wondered if police and prosecutors “were in a little bit of a rush” to win a conviction — asked the lawyers to file post-hearing arguments in writing.

In a perfect world, Mason said, he will let Johnson know if he is going home “for the holidays or not.”

About 20 activists and exonerees gathered outside the Carnahan Courthouse in St. Louis today to stand in solidarity with Lamar Johnson. Bobby Bostic (green shirt) spent 20 years in prison with Johnson before his release on Nov. 9. “To see him still there, it hurts.” pic.twitter.com/z9yu6buYZM

— Monica Obradovic (@MonicaObradovic) December 12, 2022