A Family Photo Album Holds Black History

The practice of photography has a long and complex relationship within the Black diaspora. As Tina M. Campt articulates in her 2012 book, Image Matters: Archive, Photography, and the African Diaspora in Europe, “The photographic image has played a dual role in rendering the history of African diasporic communities, because of its ability to document and simultaneously pathologize the history, culture, and struggles of these communities.” At its worst, the craft has been utilized as a means of data collection and racial caste enforcement, going back to the slave daguerreotypes of Louis Agassiz, colonial postcards that reinforced a mammification. But the visual medium has also provided a robust means for Black people across the globe to reject the negative stereotypes assigned to them. Black photographers and photography showcase how Black people see each other and the Black cultures formed in spite of the all-consuming force of white supremacy.

There are well-known photographers and curated collections that speak to this ethos. W.E.B. Du Bois and Thomas J. Calloway curated “The Exhibit of American Negroes” at the 1900 World’s Fair in Paris as “an honest, straightforward exhibit of a small nation of people, picturing their life and development without apology or gloss, and above all made by themselves.” Dawoud Bey’s Harlem USA championed the richness and vibrancy of Black quotidian life in one of New York’s cultural epicenters; Malick Sidibé’s postcolonial studio captured the essence of Malian youth culture, showcasing movement that brought photos to life.

Renata Cherlise is quite familiar with this practice herself. Her popular platform, Black Archives, has been documenting and curating various parts of the Black experience for more than a decade now, pulling from a variety of photo archives. Her mission is written on the website’s home page in bright white text: “Black Archives is a gathering place for Black memory and imaginations.”

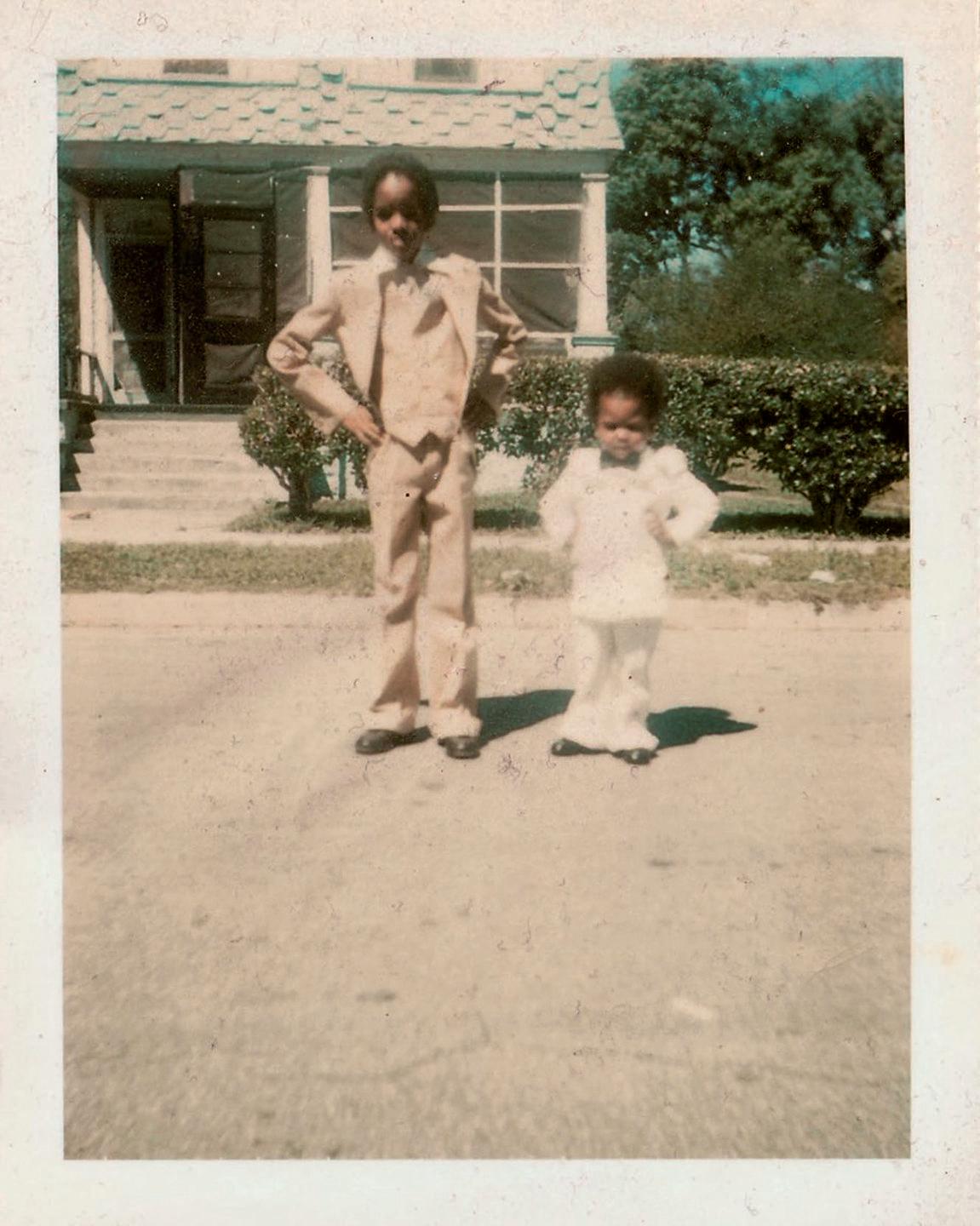

In 2019, Cherlise began a new project—a book that would pull from community submissions. “My entry point to Archives is the family photo album,” she explains. “That’s where I felt most appropriate to start.” Similar to the matriarchs in her family who preserved her family histories as many of the men passed on prematurely, the Black Archives project bears witness to overlooked Black stories. As Cherlise tenderly expresses in the book, the aim is to “[fill] the chasm of silence between the photos of where truth lives, and the black hole of the unknown”—giving a delicate interplay between her family’s archives in Jacksonville, Florida, and vernacular photography from across the diaspora.

For photographer Laylah Barrayn, the entry point is different. “My family photo album, I don’t know where it is. Through movement, and through people passing away, and I can’t locate it. I have a few photographs from it, but I can’t locate it.” Part of her remedy is found in her book We Are Present: 2020 in Portraits. It is a careful study in community, grief, and remembrance borne from processing the loss of her mother, grandmother, and the racial and social upheaval that set the world ablaze. “What [Black Archives] does is to give people like me back the family photo album,” she explains. “Family photographs—the photographs my mother made—really gave me a sense of who I was as a person, who I belonged to, and where I came from; that really fortified my identity,” Barrayn explains. “In rendering a carefully collected selection of memories, Barrayn points out, people will see themselves and their own families in the various snapshots, likening it to the classic rap song by Pete Rock and C.L. Smooth, “They Reminisce over You (T.R.O.Y.).”

Barrayn is familiar with archival and curatorial practices, having worked with writer and collector Catherine McKinley on the exhibition “Aunty! African Women in the Frame, 1870 to the Present,” a showcase that engages with the nuances and duality of a title that is simultaneously an honorific and a weapon of colonial subjugation throughout the diaspora. In We Are Present, she takes her critical eye behind the lens, using portraiture as dialogue. “The portrait held a space of questioning and held a space of conversation, healing reckoning, and comfort,” Barrayn explains. “It was very cathartic for me.”

The composition of posed and live shots forms a familiar and legible tableau—a glimpse into communities navigating an emotional spectrum throughout 12 months. The weight of communal grief is framed in the shoulders of a local funeral director, solemnly standing by a casket; the glint of a chain with the name Floyd shines on the clavicle of George Floyd’s girlfriend, Courteney Ross; the violence of police brutality in New York is denied a face, instead zooming into the taut grips of their batons as the NYPD form a barrier on Flatbush. “I’m always thinking about which frame made the cut, and what’s in the archives,” Barrayn explains. “I kind of wanted the portraiture and the people to be dominant in the visual conversation that we’ll have.”

That disposition informs the thematic cohesion of her book, which is directly engaging with human sentiment, ranging from the more festive to the more subdued and interrogatory. Homing in on singular and discrete moments with universal resonance in Black communities—from candlelit vigils in honor of the dearly departed to a girls’ night out—helps flesh out an addition to the archive that includes not only the grief and the pain, but the moments of connection, hope, and faith that round out the Black experience and offer texture and humanity.

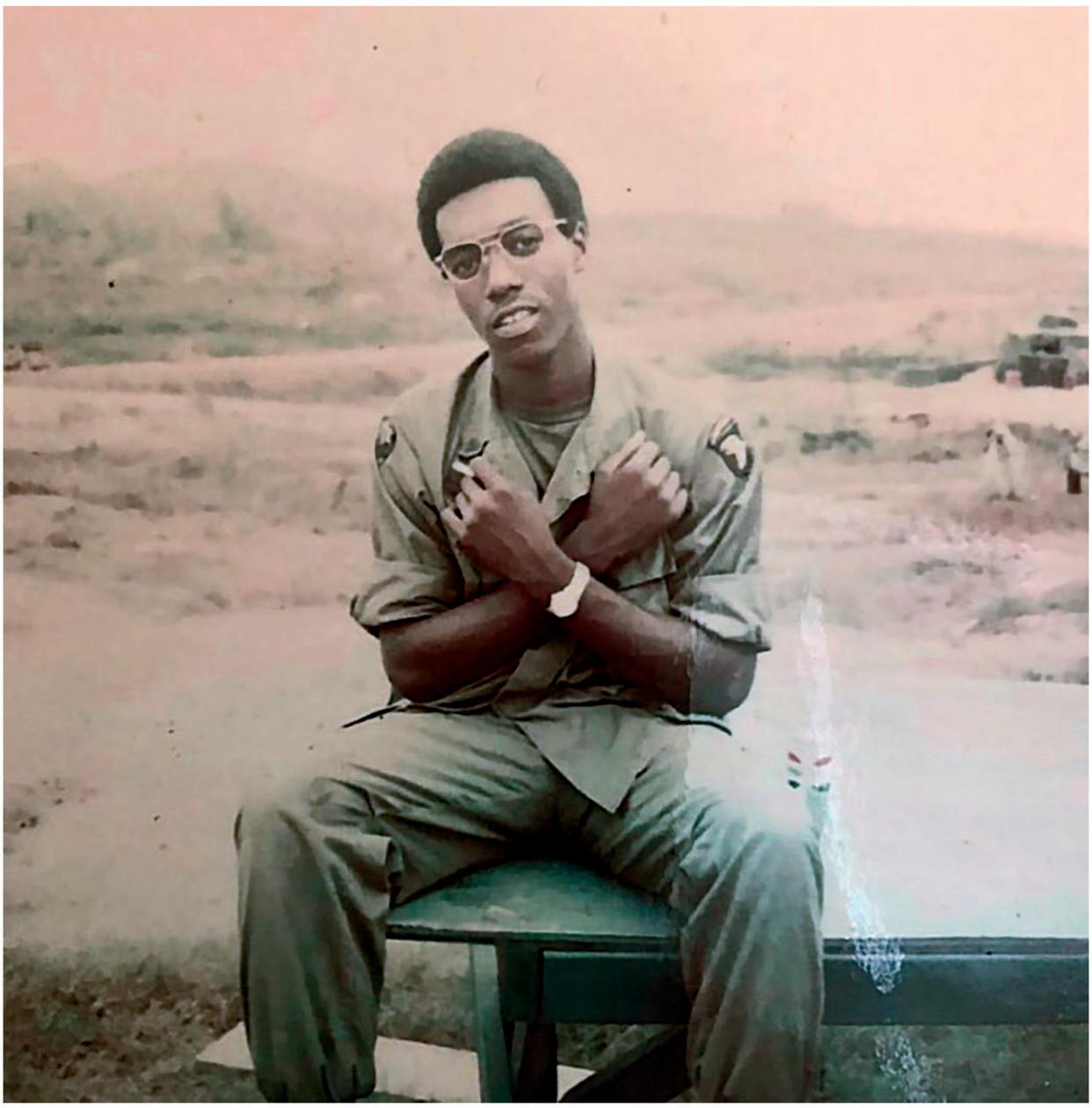

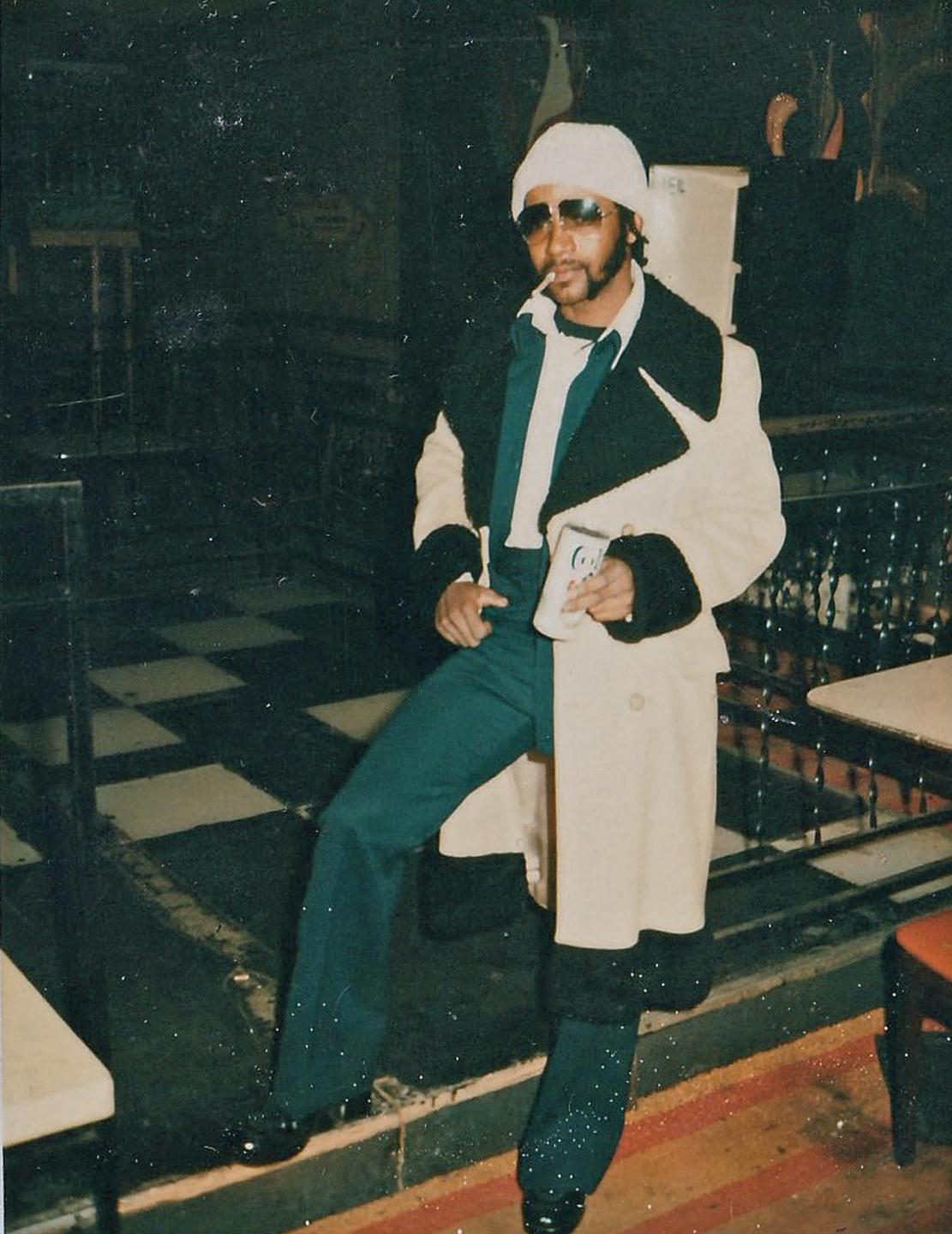

When Cherlise put out two calls for submissions in 2019 and 2020, she was flooded with responses. “I was really honored that people were sharing,” she says. “I feel like I was able to cultivate a community and credibility and trust, where people felt comfortable sharing their intimate moments with me.” As the photos came in, she began to sort them into common themes, with the concept of home serving as the architectural foundation for the sections. Some groupings are inspired: “Pictures Within Pictures,” a nod to the bevy of portraits that adorn many Black living spaces, is also an interrogation into how we can poke and prod at unanswered questions in our unanswered histories through a different lens. “In Uniform” challenges the common conventions shaped around the phrasing, including people in their gospel choir and young people in playclothes. “Sounds of Blackness” runs the gamut from a young man lounging in front an 1980s sound system, to an HBCU marching band in full swing, to the look of wonder and exuberance on a Jamaican immigrant’s face who is experiencing snow for the first time.

Each section is introduced with Cherlise honoring a family member or loved one from her own archives—and while the leading text of each section is shaped with the intention to provide the reader a solid framing of the forthcoming images, the details next to the images themselves are willfully sparse, akin to the display of a photo album, and veering away from the traps of didactic practice. “When I initially started Black Archives, my idea at the time was to create something to counter the narrative that was out there,” Cherlise explains. “I’m not really interested in that anymore. I just want to show us—I want to hold a mirror up to us so that we can see ourselves. And this is how I see us.”

It was a little over a two-year process for Cherlise to go through all the submissions, curate them accordingly, and carefully fashion text leading into each subsection. A major stumbling block was incorporating all the photos; many of the submissions she received were not originals. “The resolution of many of the photos would not, like, stand the test of a traditional printing [and] proofing process,” she explains. The COVID-19 pandemic restricted mobility and people’s ability to contact family members to obtain originals to scan and resubmit. “I felt a responsibility to try to incorporate as many of those submissions as possible, and there were cases where we were able to work with the printer to make them smaller.”

In a cloud era where memories are stored by the terabyte and photo albums are obscured by the endless screenshots and memes that are saved and abandoned, a tangible product like Black Archives reminds us of the power of intentionality and curation. Even though Cherlise has amassed substantial engagement in digital platforms, she does hope that the book stirs a revival of the family photo album as a valued artifact. The book is a visual exercise in narrative remembrance, and one that Cherlise does not take for granted; in reclaiming this communal space, she is claiming space for herself as well. She doesn’t have possession of her great-grandmother’s photos because of a dispute between her great-grandmother and her landlord at the time; her belongings, including her photos, were held hostage in a cabinet and later abandoned. She has only a singular drawing of her great-grandfather, who passed when he was 30. “Sometimes you don’t have the photos, because they were lost or taken or destroyed,” Cherlise states. “And you’re just trying to pull the pieces together.”

Cherlise once said that she thought of her platform as a “vessel to remember”—that framework is pronounced in the meticulous construction of her first book. Black Archives excels in cultivating an intimate and accessible experience—one that animates the multidimensional realities of Black existence with the power of community and acknowledgement of heritage. It is a triumph of community—one that denies us the ability to forget the ways that we celebrate our families, fight for our legacies, and support each other throughout the diaspora, from the mundane to the most significant milestones, despite consistently being socialized via white supremacist pathology to believe otherwise.

You Might Also Like