How the faith and science of forgiveness could curb retaliation from gun violence in Akron

The killing was sure to continue if Tracy Snyder said so.

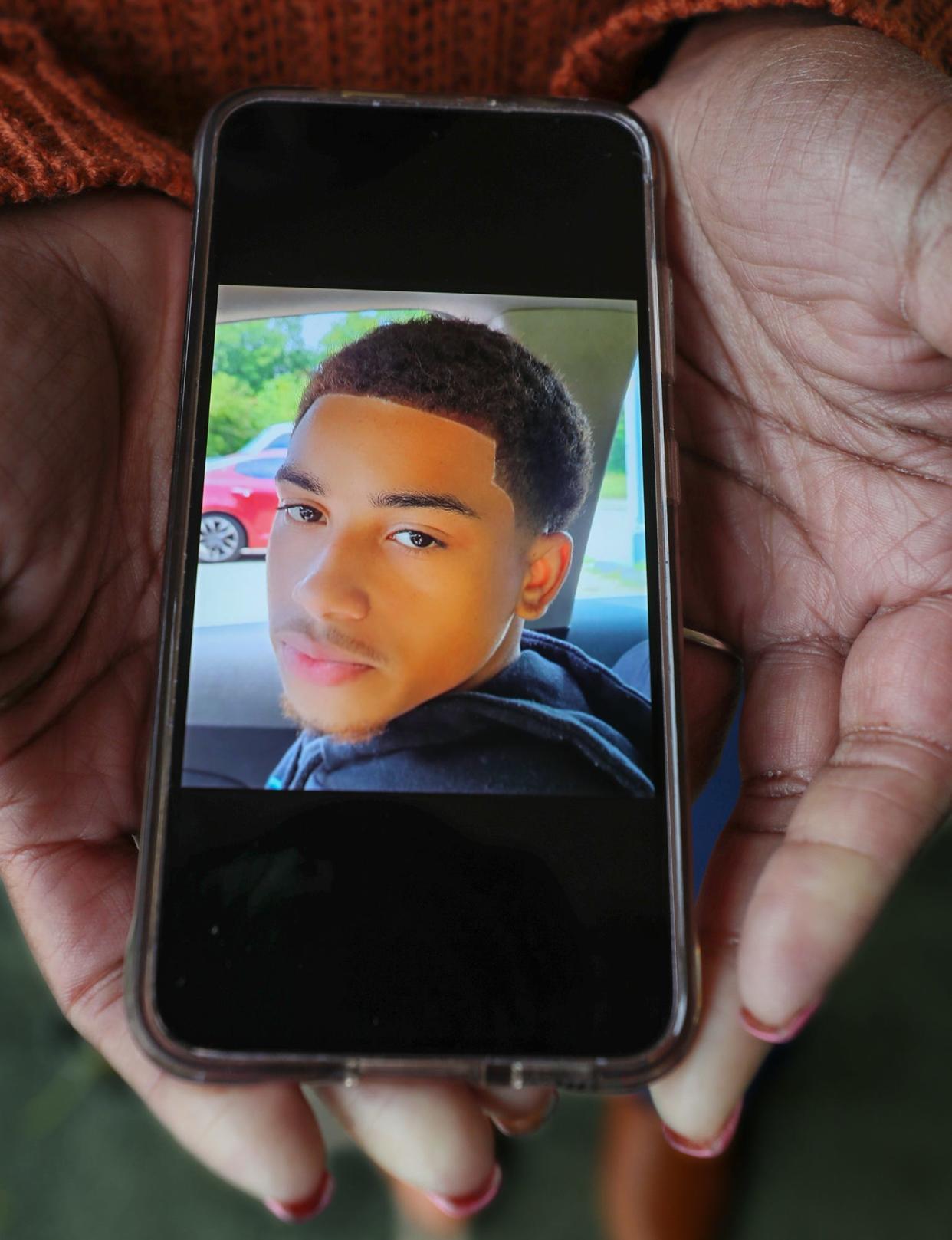

On a Wednesday in August, her grandson Antenio “Teno” Louis, a 17-year-old rising star athlete at East High School, caught a ride to football practice with a friend. From his grandmother’s house on Dan Street, they traveled 200 feet when a vehicle cut them off at the Glenwood Avenue intersection.

The driver survived five gunshot wounds. But Teno took four fatal shots to the right side of his buttocks, shoulder, neck and head. Snyder replays the killing like a made-for-television mafia-style assassination, her grandson’s assailants circling the block, messaging him days earlier about how they knew when he had to leave the house at some point.

The grandmother watched apparent strangers celebrate the “five-star kill” on social media. They knew the boy’s skill on the football field and mocked him for not outrunning bullets.

It broke her heart to see utter disrespect for life from the children of people she knew, Snyder said. Then she got the call from sympathizers offering to settle the score.

“They literally called me on the phone and said, ‘You want somebody dead?’” recalled Snyder, who was also encouraged to do the killing.

“Absolutely not,” she told them. Her world had been shattered, but not her conscience.

“I don’t want anyone to go through the pain that I'm going through right now," she said. "You know what I’m saying? Because no matter how bad a kid is, somebody loves them. And what I'm going through is unbelievable.”

The gun violence that increasingly targeted youth in Akron this year often stemmed from confrontation. Teno’s was a targeted slaying, his family said, not because the boy wronged anyone personally but because his friends acted online like they could be gangsters and Teno was a prominent athlete from a rival neighborhood, which made him trophy kill “like hunting a deer."

Teno had appeared in the background of a homemade rap video lamenting the loss of a boy his age who died of gun violence. He didn't speak a word in the video. And his grandmother tried so many times to get him out of Akron.

From deaths like his, police and victims say killing often multiplies in rounds of retaliation. Public officials and community leaders have pleaded for an end to the vicious cycle.

At least one answer, according to social scientists and faith leaders, lies in the ability to move beyond the anger and sadness of the grieving process to “some kind of acceptance,” as Frederick Luskin, director of the Stanford University Forgiveness Project, calls it.

Retaliation may be acceptable in some circumstances, Luskin said. But empathy, if not absolute forgiveness, is a skill individuals and communities must practice.

And that’s “challenging,” Luskin said, because “both vengeance and forgiveness are hardwired into our nervous systems as templates.”

Snyder is still coping with the impulsive first stages of grief: her anger and emptiness. She was Teno’s usual ride to practice. She couldn’t get off work that day. She wants her grandson’s killers, regardless of their ages, to spend a lifetime behind bars.

But she’s come to realize that there’s nothing more she could have done had she been there to drive Teno to practice that fateful August day — other than die alongside the boy she raised as her own child.

Ministers dispatched to break the cycle

Senior Pastor Deniela Williams moved toward the killings, hostage situations and assaults when she moved New Millennium Baptist Church in 2014 to Brown Street on the edge of a South Akron, a neighborhood with some of the highest reports of gunfire in the city.

“Since we’ve been there, violence has been all around us. So, we’ve got to do something,” she said in an interview weeks after Teno’s death.

Pastor Dee, as she’s affectionately called, got her degree in social work from the University of Akron and co-founded her church in 2000. Her Sunday sermons invite youths and families to unload their burden, and they’re “just really holding onto the grief and pain.”

A young man in her parish is not ready, if he ever will be, to forgive those who killed his brother three years ago in South Akron. A mother is finally ready for forgiveness in her son’s 2014 slaying in West Akron.

Williams said it's her charge to do more than console the grieving. This summer, after years of going it alone, she brought on eight ministers-in-training. Theirs will be a mission of outreach, to bring the gospel to senior citizens who can’t make it to church, to provide comfort at funerals and, in the wake of violent murders, “to talk families off the bridge of not going after people,” Williams said.

“It’s what churches should be doing,” she added. “It’s our mission. We exist to bring light to the darkness.”

'You have to explain the process of how to forgive'

Teno’s grandmother, Tracy, said her best friend lost a son to gun violence in 2018.

“The police never talked to her. Not one single time,” said Tracy Snyder, who inquired about the boy’s case while calling detectives about her grandson’s murder. “

She said police told her the murder of her best friend's son will never be solved.

"Just that, point blank," she said. "So, I can see people wanting retribution if their cases will never be solved.”

For now, Teno’s family is healing.

“I think we'll all be better once we know they capture all the people and perpetrators involved,” Teno’s aunt, LaTia Snyder, told the Beacon Journal in October before the last of three people charged in her nephew’s slaying was arrested. “And once they go through the justice system, and that's handled properly. But you know, I think we all just, you know … my family is just human right now.”

LaTia Snyder works as an intervention specialist. She sees the struggles of youth daily. But Teno’s death is the first time tragedy hit so close. She hears what her church leader, Pastor Dee, says about forgiveness, and it makes sense.

“But you have to explain the process of how to forgive,” she said. “I know my pastor went over just how important it is to forgive but you got to tell us how to.”

Research shows that faith can predispose people to empathy, said Luskin, who witnessed the forgiveness of Black families of the nine people killed in 2015 by a white supremacist at Mother Emanuel AME Church in Charleston.

“I met some of those people through my work,” said Luskin, “but it was because they had practiced.”

And LaTia Snyder is practicing.

“You got to be right with God, so you can move forward,” she said, “because without him you're just thinking about retaliation. Or you’re just thinking of the negative aspects. But, I don't know. That's just with me because not everybody is religious like that.”

Strategies for empathy and forgiveness

In his pursuit of forgiveness, Luskin has sat down with grieving Black families in Oakland, California. He’s studied truth and reconciliation after genocide in Rwanda and South Africa. He’s worked with others to convene opposite sides of bloody conflicts in Northern Ireland and Sierra Leone, Africa.

The late psychiatrist Elisabeth Kübler-Ross’s five stages of grief offer a framework for understanding responses to loss.

“There's usually anger and, too often, decisions are made in anger. But if grief proceeds, it also leads to sadness and emptiness and fear — the other side of anger. And then that leads, usually, to some kind of acceptance of 'things that happened that I didn’t want to happen.'

"But if you don't go through anger and sadness, if you just stay in anger, then you lose the capacity to grow from what happened.”

That’s the key to “actual grieving,” Luskin said. It requires time and suffering. But there are ways grieving people can prepare to respond in the healthiest way for themselves, their loved ones and their broader community.

They include:

“Mindfulness meditation practice to calm down the nervous system, so you're not so aroused all the time,” Luskin said.

Promoting “stories not just of victimhood and of revenge but stories of people who dealt with it better.”

Teaching “compassion for our community. Teach us how to hold our wounds and losses with compassion for our suffering, not just anger towards those we perceive as the perpetrator.”

“So those are some strategies that are very simple,” said Luskin. “But most of these are designed upfront to make sure you're not just listening to the limbic system and the amygdala shouting at you that 'hell has broken loose' and you have to respond that way.”

Listening to the hearts and grief of youth

Courtney Shadie, 35, is one of the eight ministers helping Pastor Dee as part of the fabric of faith in Akron trying to comfort pain and disrupt violence.

Shadie's brother-in-law, Gregory Lee Williams, whom she called her "brother-in-love," was shot dead in 2020.

We want to hear from you: What are your ideas for combatting gun violence in Akron?

“It's really sad to me that retaliation is the first instinct in our community, because I’ve lived it firsthand,” she said.

“You see the hurt and the pain in their children's eyes,” she said of fallen and surviving family members.

Shadie recalled the last Sunday in August. The morning sermon was for children “to hear their hearts, to hear their grief and to hear the number of funerals that some of them have attended over the summer.”

They’re pulled into the streets by the influences of social media and the bad role models they see on television or in their neighborhood.

Akron in the Crossfire: Read more stories from the Beacon Journal series

At 35, Shadie had to reflect on how life has changed for today's youth, like a boy that Sunday morning who asked the congregation to pray for a best friend whose girlfriend’s body was dumped in an alley in East Akron.

“I went to one funeral in high school and it was because she had sickle cell anemia,” said Shadie. "It wasn't to gun violence or anything street related.”

Reach reporter Doug Livingston at dlivingston@thebeaconjournal.com or 330-996-3792.

This article originally appeared on Akron Beacon Journal: Akron ministers fight gun violence with faith, forgiveness and empathy