Faith: Path to motherhood takes a painful detour in infertility

"Ooh, dream weaver I believe you can get me through the night Ooh, dream weaver I believe we can reach the morning light"

— “Dream Weaver,” Gary Wright

I was a teenager before I found out that my beloved Bunny (a stuffed animal version of the little rabbit in blue striped PJs who struggles to get to sleep from the book "Goodnight Moon") whom I thought had been with me since birth was actually Bunny IV.

Each time my parents told me it was time for Bunny to go to the “stuffed animal spa” for a night, they were actually off to Barnes & Noble to purchase a fresh and fluffy one. The reason I didn’t pick up on this for so long was that it was actually possible to send the other staple companions of my childhood, my American Girl dolls, to the doll hospital and have them returned healed from whatever playtime misadventure had left them worse for the wear.

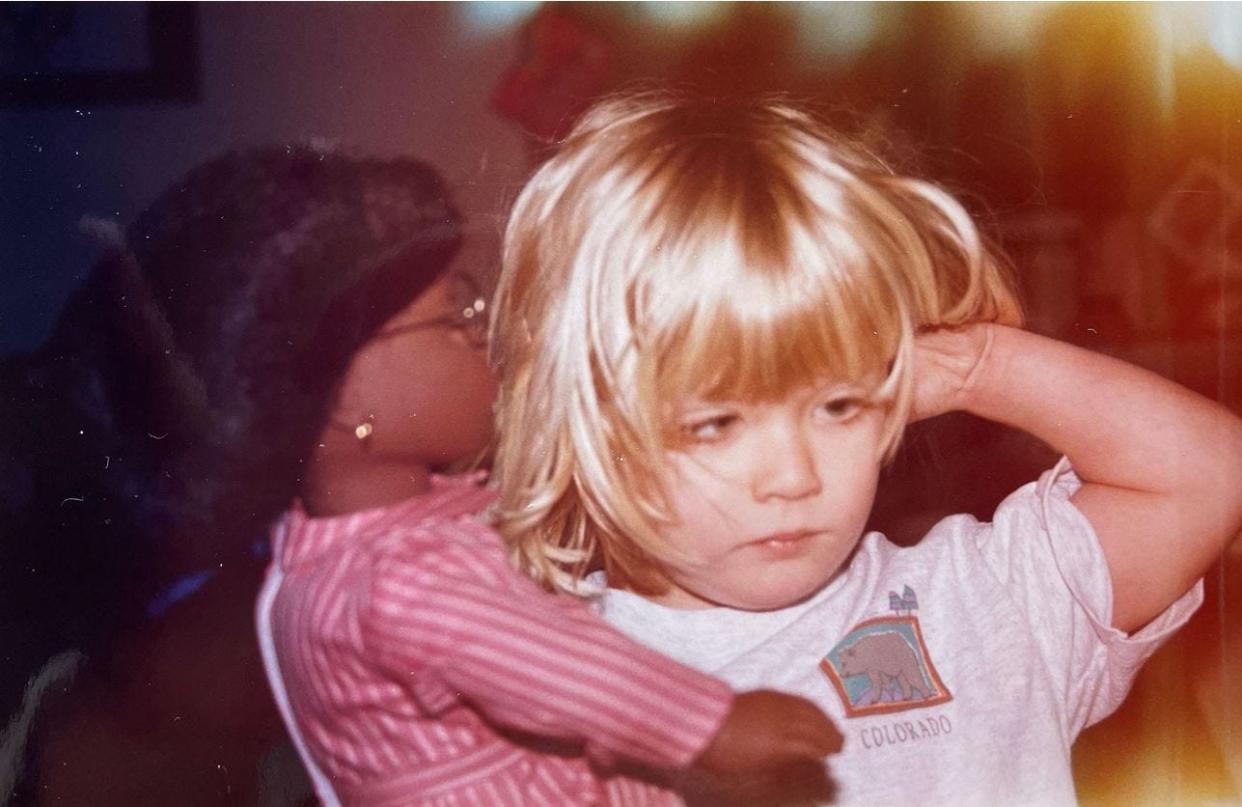

Apart from the series of stories that each historical American Girl comes with, my particular dolls had elaborate narratives I constructed for them. For example, my first two dolls and the eldest sisters of the bunch, Addie and Josefina, were adopted. Addie also had type I diabetes. Kirsten had a lot of behavioral issues at school. Her teachers called a lot (as it happens, so did mine).

I clearly used my dolls to help process that world around me, and it is telling, looking back, that I intuitively positioned myself as the mom in my imaginative play and as an adoptive mother specifically. Because it wasn’t for a few years after I opened that first American Girls box that I understood that I would never be a biological mother.

My infertility is a result of a genetic condition called Turner syndrome, which occurs when all or part of the second X chromosome is missing in someone who is biologically female. Somehow the pieces locked together in my 8-year-old brain that my chromosomes not matching the standard recipe (might mean the ingredients to turn me into a mom one day might look a bit different too.),

I asked my mom if I had a daughter, would she have Turner syndrome, too? And to her huge credit, she explained that I wouldn’t be able to get pregnant in a developmentally appropriate, but honest way. What I imagine was the hardest choice for her in the moment gave me invaluable time to cope and consider my own choices regarding motherhood.

I have had 20-plus years to move between the stages of grief around infertility. In many ways, I feel fortunate to have been given at least some possible route options for my journey to parenthood long before I was ready to even start looking for that exit.

People can get detoured at any number of mile markers on this journey, from my starting point all the way into pregnancy, or even after having carried a previous pregnancy to term. And the process of either getting back on the road or planning a new trip entirely is distinct to each of us. What I feel unites all infertility journeys is the feeling of grieving the intangible — of having to lay to rest a vision of a possible life path.

With this dream grief, there is no established ritual, no resting place to lay your flowers. Someone attempting to realize their dream of parenthood who lost an embryo in a failed IVF transfer or miscarried or had an adoption fall through doesn’t have a photo to point to and say, “This is who I loved and lost.” But they imagined who that potential child might be. They loved that idea of a future with them. And they feel their absence.

At some point in our lives, we will all have to grieve a dream — the job or relationship that didn’t pan out, the school you didn’t attend, the home you never got the keys to. Roads that will dead end, be closed or have a toll higher than we can afford to pay and leave our brains screaming “rerouting!” like a GPS on the fritz. Pull over. Take some time. You’re not crazy — life is.

Former Olympic figure skater Tara Lipinski and her husband, who spent five years navigating infertility before having a child through surrogacy, begin each episode of their podcast "Unexpecting" (recommend a listen especially for anyone considering going through IVF treatment) with the tagline “just because our path might look different doesn’t mean we’re lost.”

So to all my fellow dream grievers this Mother's Day: you’re not the only one off-roading. I’ve got my headlights on for you, and I believe we can reach the morning light. The view might not be the one in the travel brochure, but it’ll still be sunrise.

Fiona Wilson lives and works as a teacher in Philadelphia but still considers Austin home. Her writing about her experience living with Turner Syndrome appeared in the book "Standing Tall with Turner Syndrome" and she currently runs the “Not So Lonely Hearts Club Blog” at https://thenotsolonelyheartsclubblog.wordpress.com/. She plans to pursue parenthood in coming years.

This article originally appeared on Austin American-Statesman: Faith: Infertility sometimes part of motherhood