Explorers Found an Extraordinary Underwater Wall That’s 10,000 Years Old

A research vessel in the Baltic Sea discovered a half-mile-long stone wall underwater dating to over 10,000 years ago.

Experts believe that the wall was used by Stone Age hunters to corral reindeer.

The wall was located by happenstance using echosounders during a university class trip.

Don’t sell the hunters of the Stone Age short when it comes to ingenuity. New clues continue to pop up showing the creative methods they employed to make the laborious task of finding prey easier. But sometimes, you need to look under the sea to find it.

During a week-long University of Kiel course conducted on a research vessel in the Baltic Sea, the class stumbled upon a magnificent find—70 feet below the water’s surface off the coast of northern Germany, in the Bay of Mecklenburg. They discovered a stone wall more than a half mile long that likely dates back to at least 10,000 years ago. Experts believe that the wall was once used as a tool for an ancient hunting strategy, meant to funnel reindeer into a shooting blind.

The students’ find led to further research, which was published as a study in PNAS. It was led by Jacob Geersen, who is now a marine geologist at Leibniz Institute for Baltic Sea Research.

“Usually if we go somewhere and do these measurements,” Geersen told NPR about the echosounder measurements, “then we find something interesting.”

They weren’t quite sure just how interesting it was at first, but they soon found out. “The site represents one of the oldest documented man-made hunting structures on Earth,” the authors wrote, “and ranges among the largest known Stone Age structure in Europe.” But the structure’s stones alone were enough to pique intrigue and further investigation.

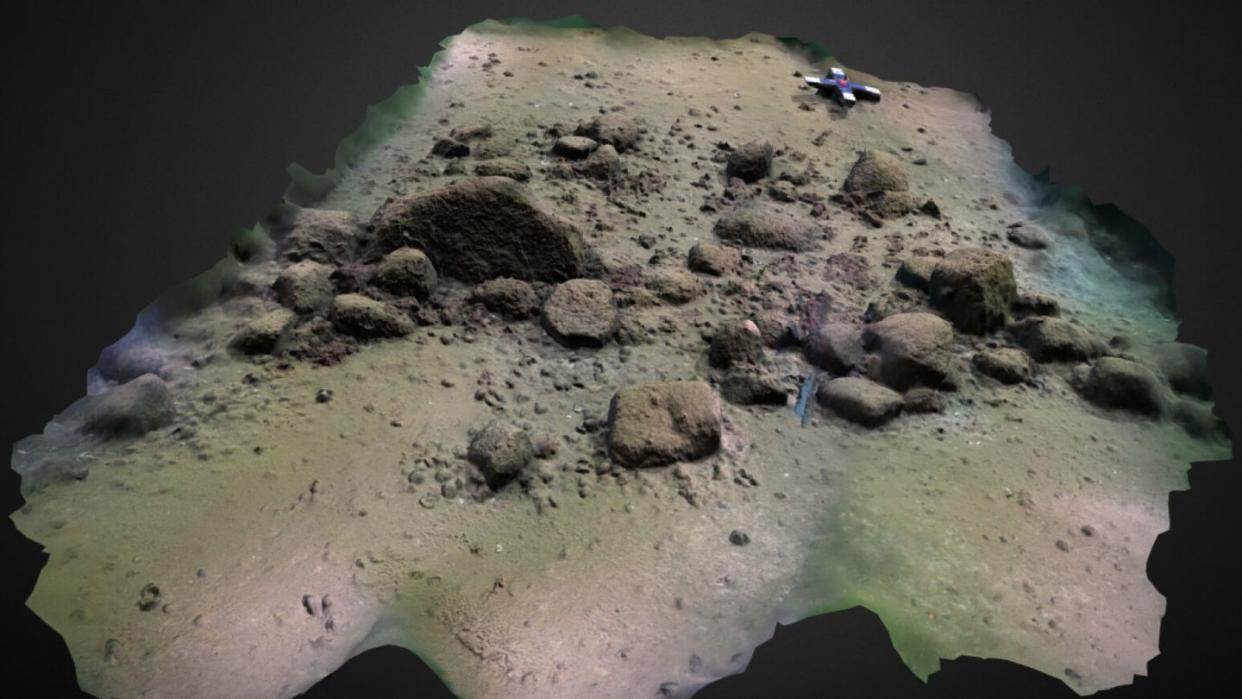

A year later, Geersen returned to the site with a fresh class and team, and confirmed that thousands of rocks were creating a 1.5-foot-high wall. “It’s usually small stones—like tennis or soccer ball size—so movable stones,” he said. “But then at some places where we have a large stone, the direction of the wall changes.”

The research featured both shipborne and autonomous underwater vehicle hydroacoustic data (with up to a centimeter range resolution), sedimentological samples, and optical images. The team believes that 1,673 individual stones were placed side by side for.6 miles “in a way that argues against a natural origin by glacial transport or ice push rides.”

Running adjacent to the sunken shoreline of a paleolake, the stone wall was likely used for hunting Eurasian reindeer. And since reindeer are known to follow walls, it makes perfect sense that the stone structure—with water from the lake or bog on the other side—would have led the animals to exactly where the hunters wanted them to be.

Berit Eriksen, a prehistoric archaeologist at the University of Kiel, said it was tough to believe this was a manmade structure at first. But she was eventually left with no other option. “The only way you can kill this amount of reindeer is if you drive them into a shooting blind, if you cut them off at the pass somewhere,” she told NPR.

Now, the ancient hunting wall has come to represent more than just a clever find. “It will become important,” the authors wrote, “for understanding subsistence strategies, mobility patterns, and inspire discussions concerning the territorial development in the Western Baltic Sea region.”

You Might Also Like