Exclusive: Are Cincinnati area schools banning books? Records show which books and where

Lakota school board member Darbi Boddy looked down at notes on her cellphone at an October board meeting.

“Separate Is Never Equal: Sylvia Mendez and Her Family’s Fight for Desegregation,” a children’s book she said was in one of the district’s elementary schools, is “a backdoor racist book, at best,” she read from her notes.

It should be off Lakota school shelves, Boddy said. She requested the district's superintendent get to the bottom of the issue as soon as possible.

Book bans, threats of book bans and challenges to other K-12 curriculum have taken center stage at school board meetings in recent years. But according to an Enquirer analysis of hundreds of emails and complaint records, there isn’t an army of parents going to battle against the region’s public schools over book offerings and curriculum.

Instead, a persistent few are challenging library catalogs at a handful of schools. Those challenges lead to hours of overtime work for the teachers, administrators and community volunteers who diligently review the complaints and, in most cases, decide to keep the challenged materials available to students − though sometimes the books are moved to a principal's office, only to be checked out with parent permission.

Sometimes requests came through for books that hadn't been checked out in years. And sometimes, the books challenged weren't on schools' bookshelves in the first place.

“Separate is Never Equal” was not on any book orders for Lakota Local Schools, Interim Superintendent Elizabeth Lolli confirmed to Lakota school board members via email later that week. But one copy of the book was found at Wyandot Elementary. The book isn’t required reading, Lolli wrote, and she did not direct its removal.

“It’s an appropriate book,” she wrote to school board member Julie Shaffer.

According to PEN America’s Index of School Book Bans, “Separate is Never Equal” was banned by two school systems in the 2022-23 school year – one in Florida and one in Texas – and was on the nonprofit's list of most banned picture books the year prior. The children's book tells the true story of the Mendez family, who fought to desegregate schools in California seven years before Brown v. Board of Education.

The Enquirer requested records from the region's 64 public school districts related to book and curriculum challenges in the 2022-23 school year, including written complaints from community members and any directives from administrators for teachers to avoid certain topics in the classroom.

The review includes all public school systems in Ohio’s Butler, Clermont, Hamilton and Warren counties and Northern Kentucky’s Boone, Campbell, Kenton and Grant counties. All but two local school districts responded to the request, most of which said they had not received challenges in the 2022-23 school year. But more than 20 districts responded with records.

See the list of challenged books at the end of this story.

A smattering of parents and community members in the region sent in dozens of requests and challenged more than 35 book titles in the 2022-23 school year, according to an Enquirer analysis of complaint records.

Districts at the heart of culture wars had little to no official complaints

Forest Hills School District, which made national headlines over the last three years while parents and school board members fought over the appropriateness of diversity and inclusion topics for students, did not have any book challenges in the 2022-23 school year, according to Josh Bazan, the district's communications coordinator. He declined to set up further interviews on the subject.

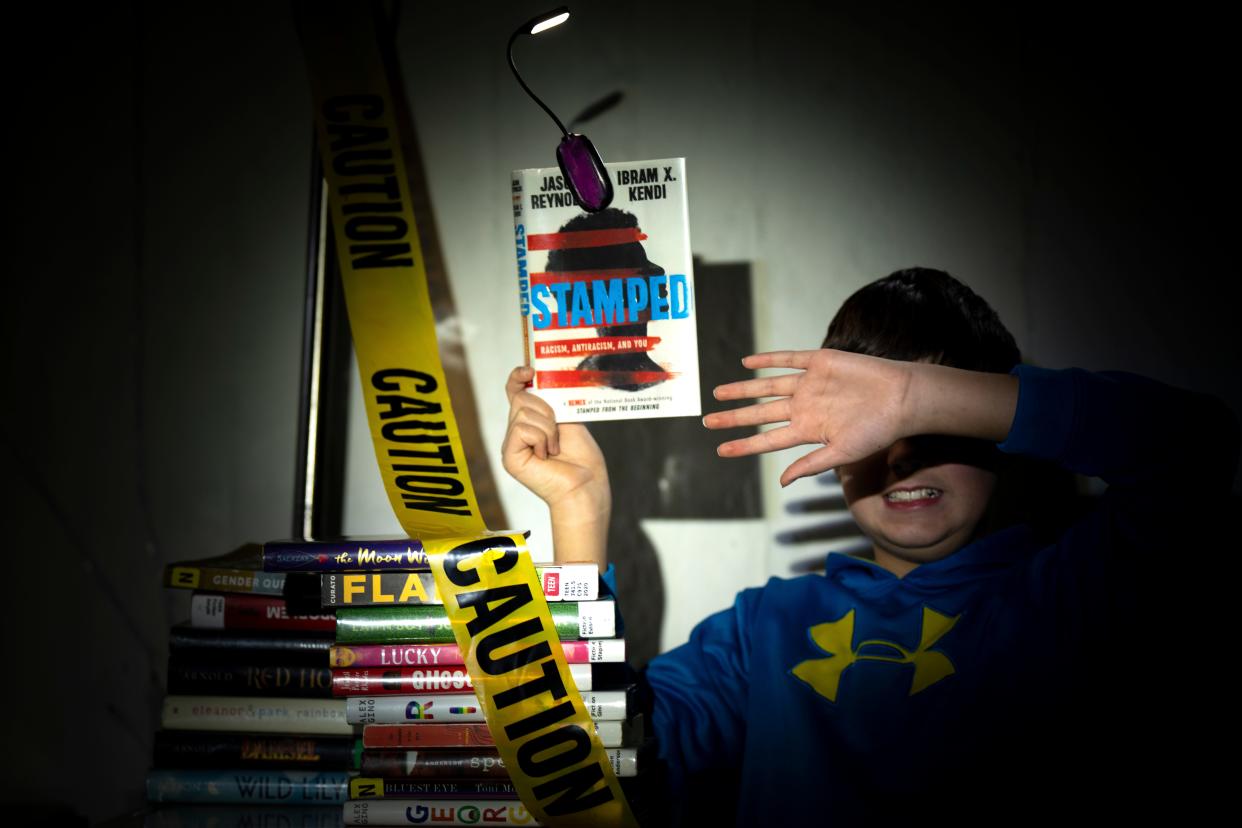

And while there were a handful of questions about specific assignments from parents at Lakota last school year, there was just one question about the inclusion of a book − "Stamped" by Ibram X. Kendi − in the district's libraries. The district doesn't carry the book, according to email records.

There aren't many official complaints about curriculum or books that make it to the district level, said Lori Brown, Lakota's executive director of curriculum and instruction. Parent concerns are typically resolved with their child's teacher, often in person or over the phone, leaving no paper trail.

There haven't been complaints about specific books directed at the district's community curriculum advisory team, either, Brown said. The team, which formed last spring, reviews new curriculum proposals and addresses community questions.

"It's been very positive," Brown said. "We haven't really had a whole lot of hot topics coming up."

Everything looks different online, though. Brown sees the Facebook posts questioning lessons and books supposedly used at Lakota and said many of those accusations are based on misinformation or taken out of context. Her team looks into those concerns when they see them on social media, even though they aren't official complaints. She encourages anyone with legitimate concerns about potentially inappropriate content being shared in Lakota schools to submit those questions online.

The requests: Some books available to students explore sexual and violent themes

Mirna Eads, a nurse who lives in Fort Thomas, Kentucky, challenged dozens of books at Fort Thomas Independent School District, Campbell County Schools and Newport Independent Schools during the 2022-23 school year. She doesn't currently have children in any of those districts – her son graduated in 2022 from Highlands High School – but is convinced "there are rogue teachers out there" and says schools are indoctrinating children with social and emotional learning, critical race theory and socialism.

Eads led Campbell County's Moms for Liberty chapter until the national organization removed her in November. The chapter dissolved after Eads posted a picture posing with members of the far-right Proud Boys group at a Protect the Children rally in Frankfort. Members of Moms for Liberty, a national dark money group whose "mission is to organize, educate and empower parents to defend their parental rights at all levels of government," are known for challenging books. Headquartered in Florida, Moms for Liberty launched in 2021 and recently the Southern Poverty Law Center designated it an "anti-government extremist group."

Eads' quest to protect children from what she believes are inappropriate books has slowed since her removal from Moms for Liberty and since a new Kentucky law passed stipulating schools need only address book challenges from parents or guardians.

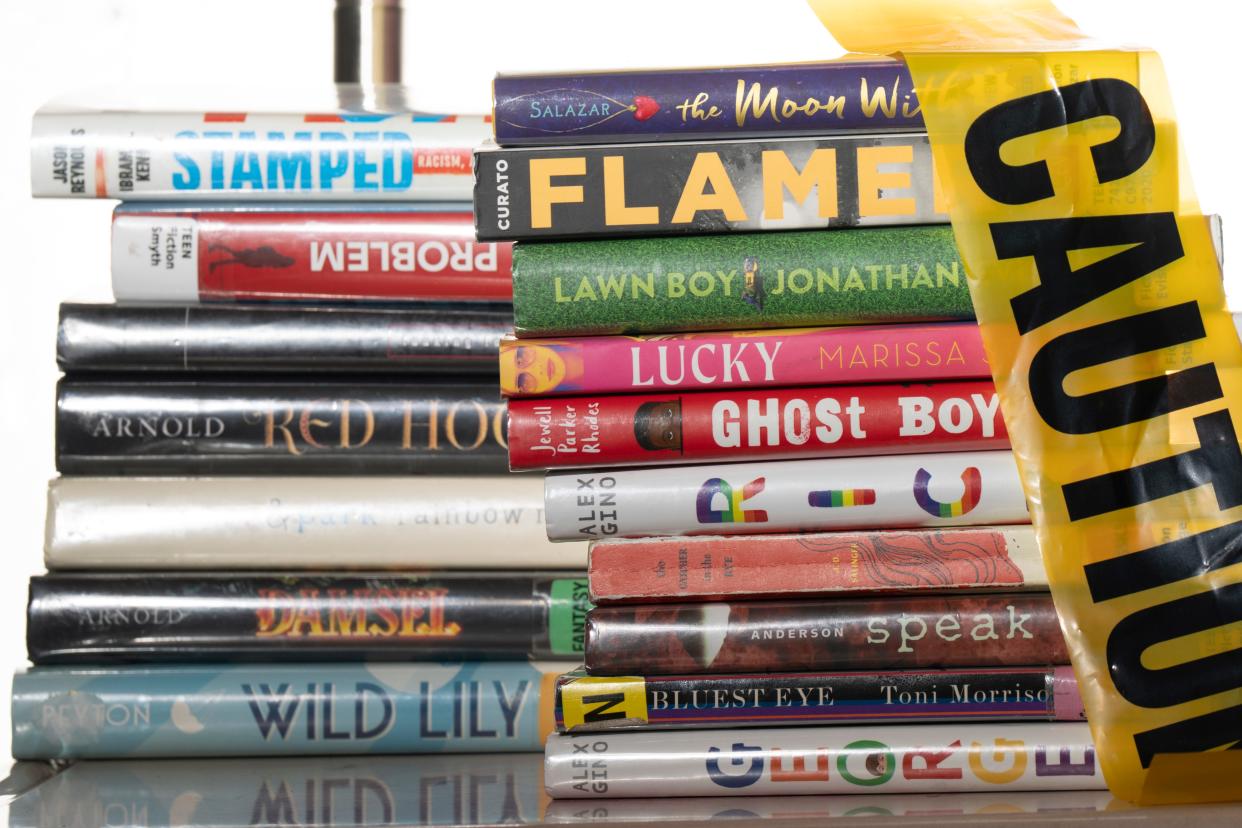

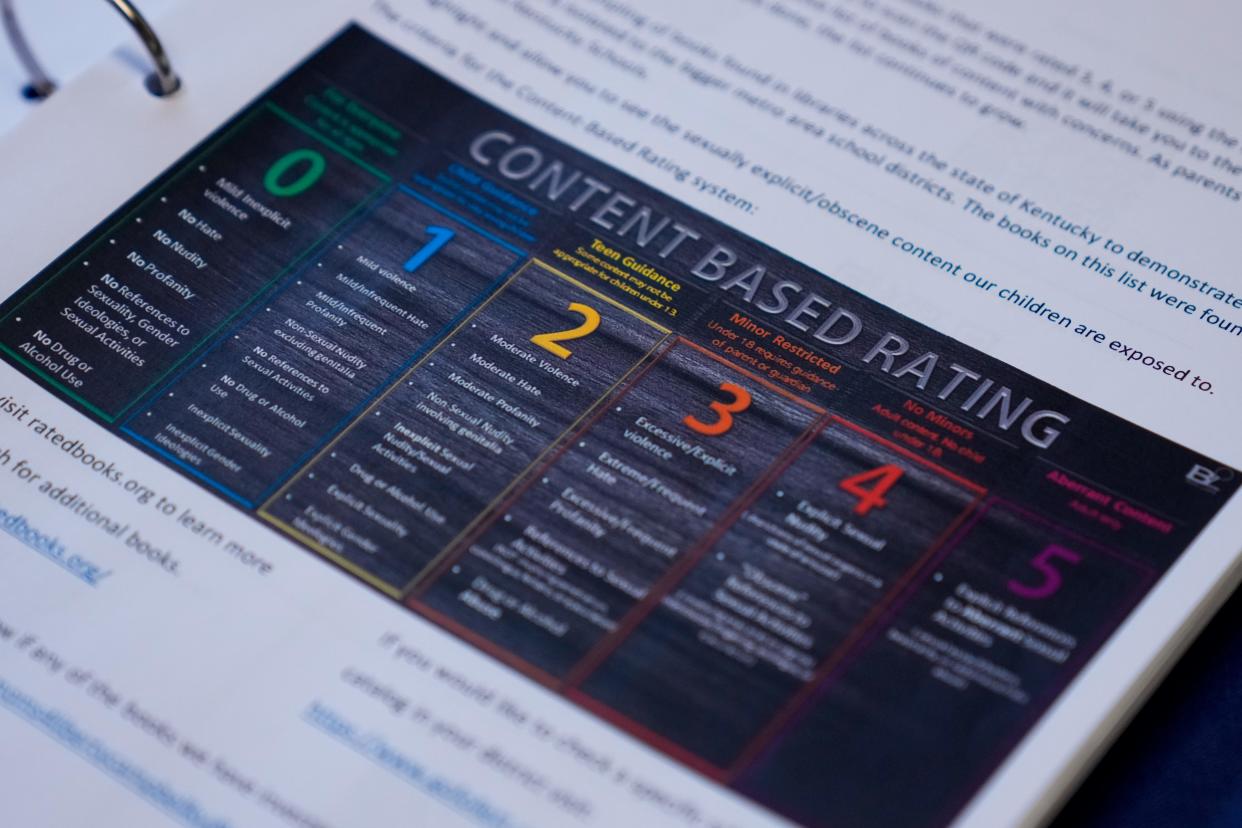

Still, she keeps in touch with current school parents and keeps a blue binder stuffed with excerpts from books such as "Milk and Honey" by Rupi Kaur; "Flamer," a graphic novel by Mike Curato; and the manga series "Assassination Classroom" by Yusei Matsui. Those books include passages and images describing female genitalia, masturbation and in-school violence and are listed in library catalogs at local schools.

These titles just scratch the surface of a world of inappropriate books that normalize sex, pornography, drug use and pedophilia, said Eads. She doesn't want to be seen as one of those "crazy conspiracy theorists" but said she's read these books cover to cover and was appalled by the graphic sexual language she found.

"I'm not Catholic, but if I had been Catholic I would have been in the confession booth every five minutes" while reading these books, Eads said.

Similarly, Rebecca Vehr requested reviews of several books at Kings Local Schools. Vehr is not a parent in the district, according to an administrator. Vehr did not return several calls from The Enquirer.

In her formal challenges to seven books – including "Speak" by Laurie Halse Anderson, "Rick" by Alex Gino and "Girls Like Us" by Gail Giles – Vehr wrote of the novels' graphic nature.

"This is an extremely violent, dark and depressing book," Vehr wrote in a complaint about "Speak." The book deals with themes of rape and underage drinking. "I am shocked and disturbed that the school district would allow students in grades 5-6 access to this book in the school library."

A handful of complaints lead to hours of work for administrators, volunteers

Eads was the only person who challenged books at Campbell County Schools last school year, according to district records obtained by The Enquirer. The district serves more than 5,000 students.

And Vehr was the only person to challenge books at Kings Local Schools, which is slightly smaller than Campbell County Schools. Kings is located in a northeast suburb of Cincinnati, about 25 miles from the city center.

In November 2022 Eads sent a letter to library staff listing 22 books she believed should be reconsidered and followed up with another seven books in January 2023. In her many emails to Campbell County Schools staff requesting book reviews, Eads wrote that she does not support book banning, doesn't intend to cause chaos at school board meetings and isn't trying to make extra work for administrators or librarians.

But from the very beginning of the review process, Campbell County High School Principal Holly Phelps wrote "the amount of books and the timeline (to review them) is daunting" in an email to the review committee. When the second round of Eads' challenged books came through, Phelps wrote, "I know that this is time consuming, but I appreciate everyone's willingness to help." The committee asked Eads for extensions, noting the length of some of the books as "incredibly long."

Most of the books the committee reviewed were retained, some can now only be checked out with parent permission, three were removed and one had never been in the schools' collection at all. "Lucky" by Alice Sebold, "Empire of Storms" by Sarah J. Maas and "What Girls Are Made Of" by Elana K. Arnold were removed.

None of the books Vehr challenged in Kings Local School District was removed, said Matt Freeman, the district's director of teaching and learning. He looked over the materials with a review committee comprised of teachers, administrators and parent volunteers.

"I also had to read these books, organize everything and reach out to the folks. And when I am doing that, then I am not able to do other aspects of planning, of my job, to help us move forward in our district goals," he said. "It was a lot of work."

School districts restructure, or create anew, the book review process

Book challenges last year were ultimately a good thing, even though the process was timely and at times "a pain," Freeman said.

The district didn't have formal guidelines in place to address such complaints, since it had never received a book challenge before. Through Vehr's requests, his team created a system. Now, when challenges come in, Kings staff know what to do.

Freeman said Kings also updated its process for retiring books from school libraries. Librarians look at how often the books are used and whether they are damaged, for example.

Questions about what's appropriate to share with students also prompted the curriculum review committee at Lakota.

Brown and Freeman both said they encourage parents to be involved with what their kids are reading. And sometimes teachers even notify parents when they see a child reading a book they wouldn't consider appropriate for that student's age.

But books aren't removed from shelves just because an individual finds them offensive, Freeman said, because "we have a diverse community that we serve."

This article originally appeared on Cincinnati Enquirer: Which books were banned in Cincinnati, Northern Kentucky schools?