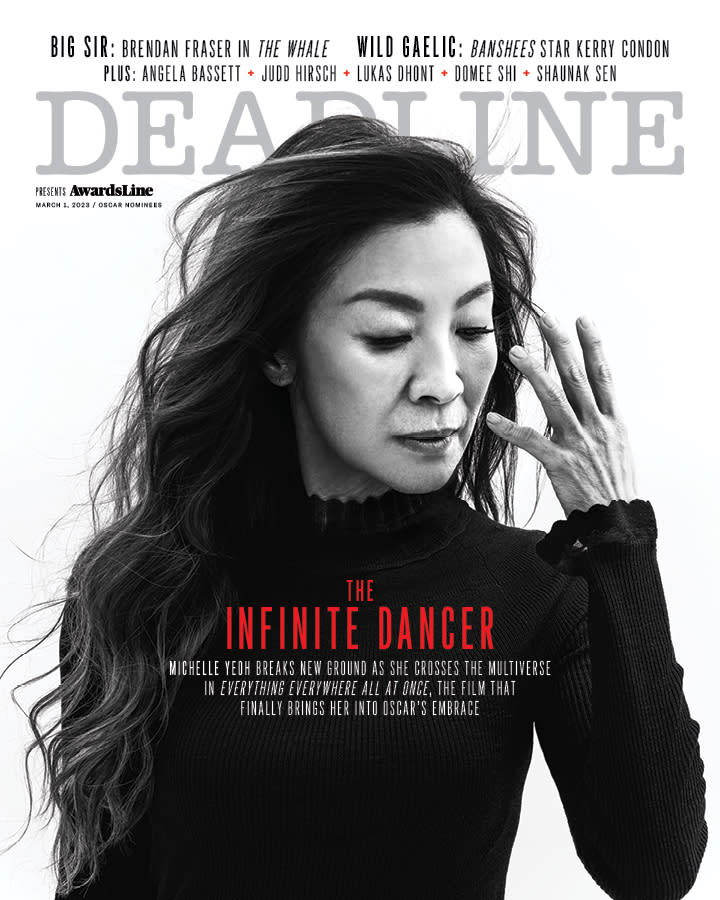

‘Everything’ Is Set For Michelle Yeoh, SAG’s Newly-Crowned Best Actress Winner, But “We Mustn’t Take Our Foot Off The Pedal”

Michelle Yeoh never imagined a path for herself that would lead to her mind-bending performance in Everything Everywhere All at Once, the film that has made her Oscar’s first Best Actress nominee openly of Southeast Asian descent and that has earned her SAG’s Best Actress prize, among other accolades. After a lifetime spent breaking down barriers, she tells Joe Utichi how it feels to have at last been invited to the ball.

Related Story

It Is ‘Everything’ Everywhere This Weekend, But Oscar Race Is Shaken In More Ways Than One – Analysis

Related Story

'Black Panther: Wakanda Forever' Star Angela Bassett On The Power Of A Story Led By Women: "I Think We Are A Very Strong, Resolute Tribe"

Related Story

Oscars: "Naatu Naatu" From India's 'RRR' To Be Performed During Ceremony

Michelle Yeoh’s mother is a worrier. Janet Yeoh has spent the past four decades watching her wildest dreams for her daughter come true. She has witnessed her ascent from Hong Kong action heroine to Oscar-nominated international icon. But when she saw Everything Everywhere All at Once — the film that has brought Michelle Yeoh the best reviews of her career, and that landed her an Oscar nomination for Best Actress, breaking new ground for Southeast Asian performers — Janet had one main reaction: “Why do you have to look so old?”

More from Deadline

“She still treats me like I’m six,” laughs Michelle Yeoh, settling into lunch at a Michelin-starred eatery in London and looking every bit as chic as she does at any red-carpet event. A superficial observation it feels important to include when Yeoh adds that if her mother could see her now, she’d almost certainly say to her, “Did you comb your hair? Why don’t you put on some make-up, and wear a nicer dress?”

“If we were back home right now, she would have laid some clothes out for me,” Yeoh says. “It’s how she shows love.”

It might be this universal truth of motherhood that has made Everything Everywhere All at Once — a multiverse-bouncing treatise on complicated family dynamics from directors Daniel Scheinert and Daniel Kwan — such an unlikely awards frontrunner. Yeoh’s character Evelyn has such a tenuous relationship with her daughter Joy (Stephanie Hsu), that in some obscure alternate universe, an even more extremely dispirited version of Joy called Jobu Tupaki would rather dispatch with all known existence than endure any more of her mother’s misunderstanding.

But what Joy can’t comprehend about Evelyn is that her mother worries because she wants nothing less for her daughter than the best possible life. Her definition of what that looks like may have to change, but Evelyn Wang is a true warrior for her family. “Moms are the real superheroes,” says Yeoh. “They carry the weight of the world on their shoulders every day. So many women do that. They march on steadfastly, but nobody ever gives them the superhero cape.”

On YouTube, which has become a repository for so many wonderful things that might otherwise have been consigned to obscurity, you can find Michelle Yeoh’s first screen appearance. It is a commercial from 40 years ago for Guy Laroche watches, though it requires the constant voiceover of a narrator repeating the brand name to make any sense of what’s being promoted. Instead, the action on-screen sets Yeoh and Jackie Chan by a lake. They ride past one another time and again, swapping horses for motorcycles, for mopeds, for bicycles. Their characters are, perhaps, falling for one another over a series of overengineered meet-cutes — after all, their passage seems far away from anything that might reasonably be classed a daily commute — but it’s impossible to speak with any kind of certainty about the ad’s storytelling logic.

As screen debuts go, it is not the finest showcase for Yeoh’s talents. And yet, as she giggles at Chan comically toppling from his bike in one scene, there’s a comfortable ease on her face that suggests Yeoh may have found her vocation.

Inside, she says, her stomach was churning. She had signed up without paying much attention to the identity of the man they told her would star opposite. She had grown up in an English-speaking household, and Sing Lung, the name they’d given her, was Chan’s Chinese name. She didn’t know it. It was only on the day of the shoot that the penny dropped, as one of the biggest stars of Asian cinema walked up to her.

But if the ad itself is largely incomprehensible, the screen presence of its female lead was enough for D & B Films, the nascent production company that had made the commercial, to offer Yeoh a contract for a feature film. She recognized the names behind the company — Sammo Hung’s reputation as an actor and director was already established, and it was co-founded by businessman Dickson Poon — but the immediate offer felt hard to trust, and she didn’t understand the complicated document they’d handed her. In fact, their offer simply seemed too implausible to be true: ‘Sign this and become a movie star.’

Yeoh had loved movies her entire life, but she had never connected the figures on the big screen with a career that real people participated in. “We didn’t really have a film industry in Malaysia at the time,” she says. “I was looking up on that big screen at Christopher Lee as Dracula, or watching musicals like The Sound of Music, but I never, ever thought it was something I could do.”

In fact, she had already experimented with acting and determined it wasn’t for her. Her first passion had been dance. Born Yeoh Choo Kheng in Ipoh, Malaysia’s fourth largest city, she found ballet when she was just 4 years old. It became her childhood obsession, and she practiced daily. After her family emigrated to the United Kingdom when Yeoh was 15, she resolved to apply for the Royal Academy of Dance in London. When she made the cut, it seemed as though her obsession could lead to a career.

So, when she took a drama elective as part of her studies, she leaned into the feeling of terror she felt when asked to perform lines on stage. “I found I got completely tongue-tied,” she says. “It was not a problem when I had to dance; that was my world. But, I was properly terrified of getting up on a stage where I had to speak. To memorize other peoples’ lines and then repeat them. I never imagined myself ever wanting to be an actress.”

Still, D & B’s offer intrigued her. “The money seemed good for me at the time, because I had never made any money before,” Yeoh says. “Obviously, later on, you find out it’s the bare minimum, but the company was taking care of my lodgings and those kinds of things. When you’re young and you want to try something, it’s not about the money. It’s about the opportunity.”

She flew back to the U.K. to seek advice from her father, who practiced law. Yeoh Kian-teik passed away in 2014, and his daughter still misses him. He was always her guiding light, so as she considered the contract, she resolved to leave the decision up to him. “If he said no, I wouldn’t do it,” Yeoh explains.

She was sure what his answer would be, and he didn’t surprise her. “You know this is basically a slave contract, right?” he told her. “You do whatever they want, they have all the power to terminate.”

Yeoh readied for the killer blow, but her father said she should do it if she wanted. “That’s the beauty of my father. It’s why we got on so well. He would never stand in the way of something he thought you really wanted to do. He always said to us, ‘This is your future. You decide. Find the school you want to study in. I’m responsible for funding it, or whatever it takes to get you there.’”

She told him: “Well, make it less of a slave contract, at least.”

When she arrived in Hong Kong, Yeoh found a film industry readily establishing its golden age. Hung and Chan were part of the Seven Little Fortunes — a legendary troupe of (more than seven) action and martial arts performers who had all trained at the China Drama Academy in Kowloon. They had begun by wowing crowds with dazzling acrobatics at an amusement park, and now were bringing some of the most frenetic action sequences ever captured to cinema screens. “Sammo Hung, Jackie Chan, Yeun Biao, and the whole lot of them were learning this elaborate choreography of action where everyone knows their steps, all their moves. I looked at that and I thought, ‘I could do this.’”

After she’d signed her contract, she told the company that she didn’t want to be cast as a damsel in distress. Instead, she wanted to get in on the action and lean on her dance training to do precisely what the boys were doing. “I didn’t want to just stand there with people shouting at me, making me cry.”

But D & B didn’t immediately recognize her Royal Academy credentials. “Are you crazy?” she says they told her. Each of their stars had spent years learning martial arts and stunt work over a decade of tutelage from kung fu Master Yu Jim-Yuen. “Do you know what these guys went through to become part of that boys’ club? It wasn’t a gift; they had to pay their dues. Not anybody can just join that club.”

The speed of production, though, was relentless. Performers were often engaged on two or three movies at any given time. Action, comedy, drama — sometimes all three — churned through the production houses apace, and there was a constant and eager demand for new films. D & B was fast becoming one of the key players, so their reticence didn’t last long. A year after her feature debut in Hung’s The Owl vs. Bombo, Yeoh landed her first action lead in Corey Yuen’s Yes, Madam!

It remains one of her favorite experiences, and the film was a quick hit. Yeoh became a star that audiences actively sought out, and the stunts became ever more elaborate. Production was a beautiful mess of loose plots strung together without scripts. Yeoh would count to 10 on cue, and someone would later figure out words to dub over her so that a rudimentary story could be kit-bashed from a mishmash of sequences. “If it was a comedy, you’d go from skit to skit,” she explains. “If it was an action movie, it would be stunt sequence after stunt sequence. You’re a pilot meeting up with the thieves. You’re a detective going after the criminals. There was never any backstory.”

She remembers working on a movie called The Seven Princesses (also known as Holy Weapon, because the titles were often as elusive as the plotlines). “There were seven of us, of course, but there was only one day of the shoot we could all get together. We were always running from set to set. So, they lined us up and said, ‘Everyone look to the right, react, then look to the left… OK, now just four of you… OK, now the other three…’” In short, there was very little acting. “They just wanted to cover their asses, basically.”

But it wasn’t as if she knew any other approach. Yeoh recalls re-encountering an actor a few years after they had worked together on her first movie. “You know, your acting has not improved,” he told her.

“I love him for that because he was right,” Yeoh says. “I watched what he was doing, and I looked at what I was doing, and I agreed with him.” There were dozens of movies, but no time to actually learn. “We’d finish shooting a movie on Monday, and it would be in the cinemas by midnight on Friday.”

In any case, when she ruptured an artery shooting Magnificent Warriors — the latest in a series of brutal injuries from stunts that had gone wrong — Yeoh decided she might have had enough of action movies after all. She had started a relationship with Poon, and they soon married. So, still in her mid-20s, and after only a few short years of work, she ‘retired’ from acting. Yeoh had already lived several lives.

Yeoh’s retirement lasted as long as the marriage: three-and-a-half years. When she returned to the industry, she resolved to act; to figure out what delivering a performance really meant beyond the stunt choreography.

Supercop reunited her with Jackie Chan, and while the stunts were bigger than ever — and the injuries no less seismic — this time there was an established story, and an extant character to play. Yeoh worked hard to build her character a backstory she could embody. “I never could cry on command,” Yeoh says, by way of explaining the approach she came to find, and the one that she still uses today. “You can’t think of something sad — connect it to something in your own life — and use that, because that might work on one take, but it won’t work on the second or third. I learned it was much more important to be emotionally involved in the character I was playing. You have to not take anything from yourself, but to become the character. To think like her. It takes time. It takes practice. It takes effort. But it is essential for me.”

She was no longer interested in simply showing up to do a job. Clocking in and clocking out. She wanted to be a sponge, seeking advice and learning from the people around her. She wanted purpose, and the voraciousness to find it didn’t go unnoticed. “Jackie would say to me, ‘You have to stop being so bold, you have to protect yourself and not get hurt,’” she says. “He knew I came back trying hard to prove myself, and he would constantly say, ‘No, wait. Wait for the mattress. Wait for someone to watch your back.’ He took care of me, and I started to look to him; started looking to friends to guide me. I think what’s important is I never was afraid to look at them and say, ‘I know nothing; please teach me.’”

We have witnessed Michelle Yeoh’s film school education ever since. Supercop became a classic of the genre, making enormous waves beyond Hong Kong, and spawning a sequel a year later. At breakneck speed — and she was never so afraid of breaking her neck — Yeoh was honing her true craft, while her natural talent held her aloft.

Her commitment was validated when director Roger Spottiswoode cast Yeoh alongside Pierce Brosnan in Tomorrow Never Dies. She knew the legacy of James Bond and was excited about going toe-to-toe with the character. She told Spottiswoode she would do whatever action or stunt sequence was asked of her. “You’re here on merit as an actress,” Spottiswoode replied. “You’re not here because you can do stunts. In fact, you probably won’t do many of the stunts; we don’t have the insurance for that. We can double you for stunts, but we can’t double you for acting.”

She still remembers the conversation because it offered a kind of validation she had, until then, only received from longtime friends. With it came a confidence to reclaim the name to which she’d been born. When she signed with D & B, the company had insisted she go by Michelle Kahn, a name they deemed more palatable to international audiences than Yeoh. Bond producer Barbara Broccoli told her: “What the fuck? Just go with your fucking name.” She has been Michelle Yeoh ever since.

Her graduating project came in 2000 when she played Yu Shu Lien in Ang Lee’s Oscar-bothering epic, Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon. Right at home with the balletic martial arts, Yeoh instead dedicated her time to understanding what drove each of the characters she came across, as well as her own. “The thing with Ang is he hates it when people call me a stuntperson,” Yeoh smiles. “He says, ‘No, she’s an actress. It’s just a bonus that she can do stunts.’”

She is buoyed by the film’s re-release in US theaters. “I think Crouching Tiger is such a classic, such a timeless piece,” Yeoh says. “You do need to see it on the big screen.”

The enthusiasm with which Yeoh reviews the many breakings of ground across her body of work is infectious. She talks adoringly of her fans and can point to many examples where her creative choices have influenced the films themselves. On 2007’s Sunshine, for example, director Danny Boyle wanted to cast Yeoh as the captain of a space mission sent out to prevent the death of the sun. “I told him I wasn’t ready to be a captain at that point,” she explains. “I told him, ‘It’s interesting you only have one Asian in the whole thing; that you think in the future it’s still the Russians and the Americans.’”

But Yeoh won’t take credit for what she says was an observation, not a pointed criticism. Instead, it’s Boyle and screenwriter Alex Garland she praises for changing their approach. “They were quick to recognize the opportunity, and so we ended up with such a diverse cast. Benedict Wong, Hiroyuki Sanada. What a great experience I had making that.”

It is Jon M. Chu and Kevin Kwan she credits with the success of Crazy Rich Asians, without acknowledging how much her own presence in the film was a blessing for her less established castmates. “It was meant to be a cameo role,” she says, though she took the character no less seriously than any other. “Every time she appeared she made a difference. That relationship with the mother and son — there was only one scene of them together, but it spoke volumes. If that hadn’t come across, the whole thing would have fallen flat on its face.”

“Michelle has always carried this incredible, regal grace to her,” says her Everything Everywhere co-star Stephanie Hsu. “That has been her thing for so long, but what’s amazing having met her is to get to see how truly loving and egoless she is. She was bridging East and West before we were even having these conversations about representation as an industry and as a society. She has always been the glue that brought people together, just by purely loving what she does. She made people feel seen since before we had the language to talk about what that meant.”

Yeoh remembers running into a mother who had seen Everything Everywhere All at Once. “She told me, ‘I didn’t really understand the movie, but I went to see it because my daughter who has been estranged from me for some time reached out to me after she’d seen this movie.’”

Even in this moment, she’s reluctant to take her flowers: “That’s the power of the Daniels. That’s the genius of these two men who wised up and thought, ‘Our mom is a superhero, and we should write it like that.’”

Yeoh cried when she read the script for Everything Everywhere All at Once. Apart from it reminding her of the dynamic with her own mother, it felt like it was everything she had been building toward. Everywhere she wanted to go. All at once.

But it took the Daniels a little time to get it there. They’d conceived the film originally to follow the Wang family’s patriarch, Waymond. They wanted to cast Jackie Chan, then re-pair him with Yeoh as a supporting version of Evelyn; their first live-action collaboration since those Hong Kong days. They hoped to return Chan to the kind of Hollywood superstardom that had defined his career in the 1990s. When Chan couldn’t commit, they were still determined to go to Yeoh.

Says Yeoh: “I’m so glad my two geniuses said, ‘What the hell? We write weird movies anyway. Let’s just rewrite the whole thing and write it with Michelle in mind.’”

It should not have felt radical, but it did. How often does a woman over 50 get a leading role, let alone one in which she’s tasked with playing an action hero? The reinvention of Liam Neeson with Taken came out of left field for an actor better known as a dramatic classicist, but it also happened 15 years ago, and kicked off a wave of aging-action-hero movies that reinvigorated the careers of performers like Sylvester Stallone and Arnold Schwarzenegger. Their franchise, The Expendables, was to be spun off into an all-women sequel, but the project was canceled before it was ever cast.

“When you write something, you write it with the hope that you’ll be able to sell it and it will actually get made,” says Yeoh. “You think, ‘What would the studios want? What would they react to?’ So, men leading the film is always an easier sell.”

So determined were they to work with Yeoh that they even named the character Michelle. “I forced them to change her name,” Yeoh says. “I am not a laundromat owner, and that person deserved a voice. An aging immigrant Asian woman, who has never had a voice before. Nobody has given her a voice. You walk past her in the supermarket, and you don’t even give her a second glance. She’s someone quite ordinary, but we’re able to turn her into someone extraordinary.”

Hsu says she marveled at the way Yeoh took the Daniels’ high-concept multiverse hopping in stride. “The best word I have for it is she surrendered,” she notes. “She surrendered to me and Ke [Huy Quan, who would ultimately play Waymond Wang]. She surrendered to the Daniels. And I think that comes from her martial arts discipline. There are no celebrities in martial arts. You have to be egoless. You have to work for it, and you’re going to use your body and throw yourself into the fold. That’s the cloth that Michelle is cut from.”

But Yeoh says she understood the material’s deepest reaches. “I think it’s touching because it’s chaotic,” she says. “Life is chaotic. It’s unpredictable. It’s up and down. It’s weird and wild and sometimes you just have to say, ‘Well, OK then.’ Which is what Evelyn has to say to Joy: ‘Just get up and go be yourself. You don’t have to talk to me anymore.’”

She says she saw this moment of revelation most clearly with her own father. “At Chinese New Year, you wish each other bountiful, mega things. That’s the tradition. ‘All your dreams will come true,’ and all that. And, one year, he said to me, ‘I wish you enough.’ At the time I didn’t understand that. ‘What do you mean, enough?’ But when I thought about it, he was saying that regardless of how you think you aren’t living up to expectations, you’re always enough. In any universe.”

Janet Yeoh has always been right about her daughter. She’s 83 now, but she has been a cinephile her entire life, and she was certain Michelle belonged on screen. “My mom loved the whole aspect of performing,” Yeoh says. “Even now, when we throw her a birthday party, it’s like a concert. She’s doing costume changes, getting on stage and serenading everyone. She would have made a great movie star.” But if the path to Yeoh’s first American lead role and first Oscar nomination was tough, for her mother it would have been insurmountable.

When the rigors of ballet started to take their toll on Yeoh’s spine, she instead looked behind the scenes, resolving to open her own dance studio in Malaysia and become a choreographer. With trademark modesty, she describes this simple dream in dismissive terms. “Like how as a kid you might say, ‘I want to be a fireman. I want to be an astronaut.’”

Her mother would stand for none of this shyness. Instead, she signed her daughter up for the Miss Malaysia beauty pageant in 1983 — literally forged her signature on the entry form — and needled her into going. Yeoh won, leading to an appearance at Miss World, and the attention of D & B Films who cast her in the commercial that changed her life path forever. She knows now that this was absolutely the right road for her to walk, and that her mother saw something she couldn’t — or wouldn’t — at the time.

In retrospect, then, there’s a direct line between that instance of maternal document fraud and Yeoh’s Oscar nomination, which is the first Best Actress nod for a Southeast Asian woman who was able to be open about her heritage. In 1935, Sri Lankan-Māori actress Merle Oberon became the first Asian woman ever nominated for the award, but she spent her entire career claiming to have been born in Australia, so afraid was she of what might happen if she were honest about her heritage.

As Yeoh reflects on her career, she recognizes the long, winding path she’s had to forge to get to Everything Everywhere All at Once. She knows now that her future in dance would have been far from certain even if she hadn’t hurt her back. After all, there were no Asian faces in the Royal Ballet at the time she graduated. And for the longest time, she wasn’t sure Oscar interest would ever come to her, or to any of her peers. “Look at Crouching Tiger, look at Parasite and Minari,” she says. “Even though they’re being recognized as great films, none of the actors or actresses were ever mentioned. It was like people looked at the color of your skin to determine whether you were white enough to qualify.” She hopes her nomination, which she shares with Quan and Hsu in the supporting categories (co-star Jamie Lee Curtis is also recognized), is an indication that things are changing for Asian actors. “But we have to keep at it. We mustn’t take our foot off the pedal.”

Whether or not she’ll admit it, Michelle Yeoh knows the need to fight for herself, on- and off-screen. But, much as it is for her mother, sometimes it’s easier for her to urge others to fight for themselves. Indeed, when this reporter makes an offhand comment about his own insecurities, she fixes a look that instantly recalls Evelyn Wang and says — sternly — no. “We’re here because we’ve worked our asses off to be here,” she insists. “We have paid our dues. We have done whatever it took. We found ways and means to get better so that we could be seen, and so that we could improve. That’s why we’re here.”

Best of Deadline

Sign up for Deadline's Newsletter. For the latest news, follow us on Facebook, Twitter, and Instagram.