What Ever Happened to Five-Valve Cylinder Heads?

Ferrari was so proud of its five-valve cylinder heads, it changed a naming convention that ran back over 25 years. For its previous mid-engine two-seaters, the three-digit name was derived from displacement and cylinder count, but the F355 did not have a 3.5-liter five-cylinder. It had a 3.5-liter V-8 with five-valve heads.

The F50 came a year after the F355 and its V-12, derived from Ferrari's Formula 1 engine, also had five-valve heads accounting for a wonderful 60 valves in total. The F355's successor, the 360, used the 40-valve V-8, with a small bump in displacement, but that was the last time Ferrari ever used the technology. It wasn't just Ferrari either. Yamaha pioneered five-valve internal-combustion with bikes in the Eighties, Mitsubishi was the first to put the tech in a production car, the Volkswagen Group had a number of five-valve production-car engines, and even conservative Toyota experimented with the technology. By 2010, it was all gone. No one was doing five-valve heads.

To explain why, we have to get back to basics. Remember that an internal-combustion is, at the end of the day, an air pump. An extremely complex air pump, but an air pump all the same. To get more out of it, you need to get more air in and more air out. "There's basically three ways to make power in an engine," says Steve Dinan, the legendary BMW tuner and engine builder, in an interview with Road & Track, "either make the engine bigger, turn more rpm or increase the cylinder pressure."

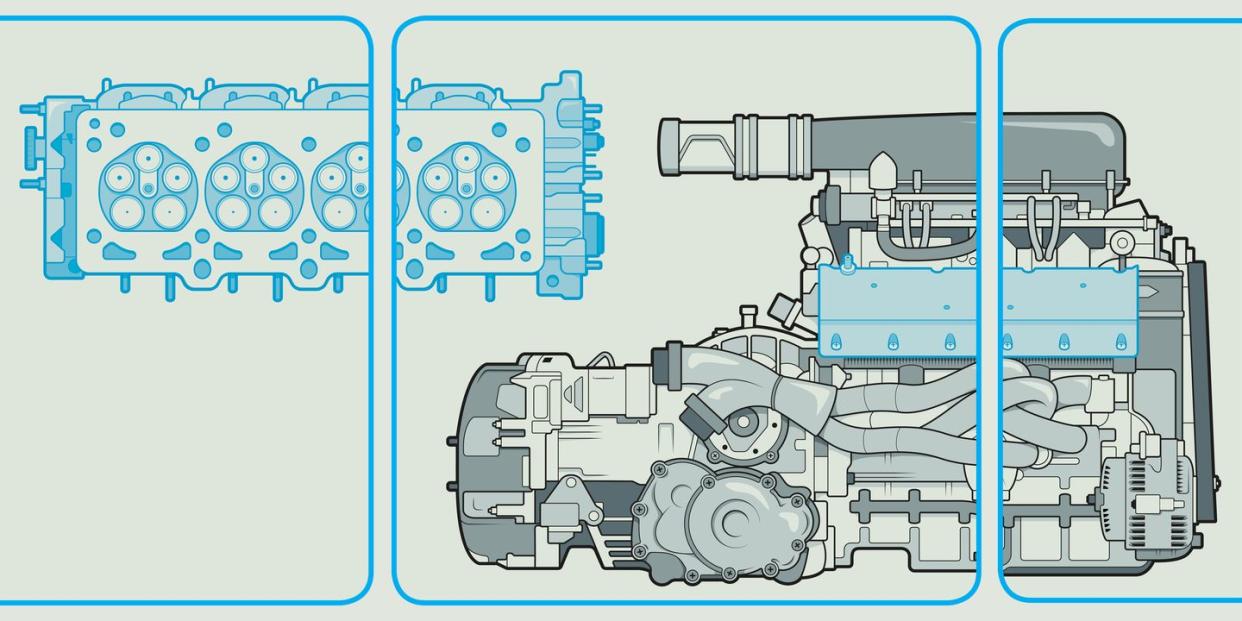

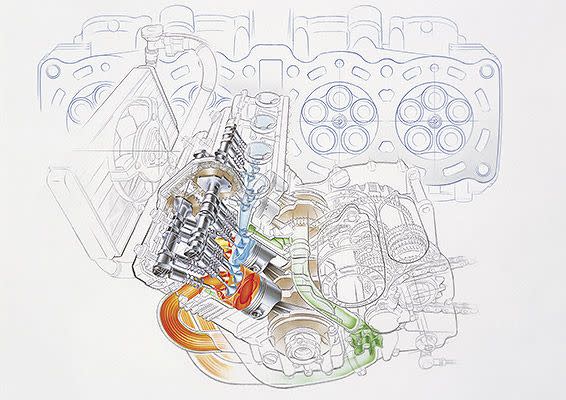

The idea behind a five-valve head was to both increase cylinder pressure and revs, making it a good idea in situations where displacement was fixed. A cylinder head with three intake and two exhaust valves could bring benefits in volumetric efficiency—how much air and fuel an engine takes in on an intake stroke—compared with a traditional four-valve head. Despite requiring smaller valves, the total circumference of the three intake valves in a five-valve head can be greater than two larger intake valves in a four-valve head. Dinan explains the theory at the time was that you could increase the intake-valve area to around 45 percent of an engine's bore with a third intake valve, compared with around 40 percent with two larger valves. Each of the valves is lighter, too, enabling higher engine speeds without valve float.

Yamaha debuted the world's first production five-valve internal-combustion engine in 1984 with the FZ750, and touted at the time that its five-heads offered 10 percent more power and five percent greater fuel efficiency than a four-valve head. The FZ750 made around 100 hp and revved to 11,800 rpm. Ferrari's first five-valve V-12 arrived in Formula 1 in 1989 and it powered cars that allowed the Scuderia to take the fight to McLaren and Williams. (Yamaha also introduced a five-valve engine in F1 in 1989, though not to notable success. The Japanese company also made five-valve Formula 2 and Formula 3000 engines.) The F355's V-8 broke new ground for automotive internal-combustion engines, with a specific output of 109 hp/liter—then a record for naturally aspirated road cars—and an 8500-rpm rev limit. Ferrari actually told R&T back in 1994 that the valvetrain was safe to 10,000 rpm.

Ultimately, however, the gains made by adding a third intake valve are small. "The problem is that because the valve stem and guide are in the way, it disrupts flow," Dinan explains. "Then you have seats between the three intake valves, and you have port geometry to feed three valves instead of two. You wind up not actually flowing any more air than a four-valve motor. I mean maybe two or three percent. It's really small, and that can easily be negated if you just make the bore two millimeters bigger and the stroke two millimeters shorter. You wind up with the same displacement and the same valve area as three intake valves."

Five-valve heads are also more complex. An automaker needs to manufacture and install more components—more valves, springs, guides, rocker arms, camshaft lobes—and little things like this add up in the world of mass production. Consider, too, that extra components mean more maintenance. Ultimately, whatever small gains in horsepower a third intake valve might bring aren't worth the extra cost and complexity, especially when an engine designer can make tiny changes to the bore and stroke of the engine.

In racing, Dinan notes, the high revving nature of five-valve engines can lead to bottom-end problems, which could be solved by going to a larger bore and shorter stroke. A shorter stroke requires a larger rod, which in turn reduces piston speed somewhat, decreasing load on the rod bearings. Over at Cycle World Kevin Cameron also notes that Ferrari's five-valve V-12—used in the not-officially-built-by-Ferrari 333 SP—was problematic in endurance racing, as adding more holes to a cylinder head increases the risk of warping and cracking. The engine originally developed for the FZ750 lived on in Yamaha road bikes until 2010, but for the 2004 MotoGP season, the company made versions of its race engine with both four- and five-valve heads. In testing, Valentino Rossi preferred the four-valve engine so that's what the bike got. The four-valve engine powered The Doctor to dominant titles in 2004 and 2005.

Ferrari's pride in the F355's five-valve engine is funny in retrospect. Months before the F355 debuted, the Scuderia abandoned five-valve heads for its V-12, going for a four-valve setup in the 412. To get higher revs, and thus improve power, Ferrari adopted pneumatic valve springs for the V-12, which did away with the need for the third intake valve. Funny too is that the F355 was Ferrari's response to the Acura NSX, one of the first cars to be fit with Honda's revolutionary VTEC variable valve-timing and lift system, which proved to be a much better solution for boosting engine performance across a wide rev range. This isn't to say that the F355's engine wasn't great, just that it represented a technological dead end.

Yamaha designed a five-valve head for Toyota's 4A-GE four-cylinder, which was used in a number of Japanese-market models throughout the Nineties. It was dead around the turn of the millennium. Even shorter lived were Mitsubishi's tiny 660cc five-valve four-cylinder used in a handful of Kei cars, and on the other end of the spectrum, the quad-turbo 3.5-liter V-12 developed for the Bugatti EB110. The VW group was the most prominent user of five-valve engines, and the last automotive holdout, thanks mainly to development led by Audi. It offered 20-valve four-cylinders, 30-valve V-6s, and a 40-valve V-8, though they were all dead by 2010.

In their day, five-valve heads made sense. They were a product of a fierce time in engine development in cars and motorcycles, on both road and track. No surprise, also, that it made its debut in Japan, then in its Bubble Era, when development budgets exploded before a market collapse led manufacturers (and their racing departments) to reign in costs.

With road cars, it's easy to see why the idea was abandoned. Using a third intake valve adds huge cost and complexity and there just isn't much, if anything, to be gained. Don't expect to see it make a comeback.

Let's go back to Dinan's three ways of increasing engine power: Revs, displacement, and cylinder pressure. Half-liter cylinders offer optimum combustion properties, and in some markets, notably China, cars are taxed by displacement. That's why we have so many 2.0-liter four-cylinders these days, and for the purposes of this thought experiment, we can take displacement out of the equation. Automakers now have two options. Revs aren't desirable in modern road cars (performance cars notwithstanding) because most consumers (rightly) want low-end torque for daily driving. Now you're down to cylinder pressure. You know what increases that greatly? Turbochargers. In a world where so many cars are turbocharged—and variable valve timing and lift, plus highly optimized combustion chamber geometries—there is truly no need for an additional intake valve.

I don't want to make it seem like I'm criticizing Ferrari, Yamaha, et al for going down this route, though. Quite the contrary. Five-valve engines are wonderful oddities, the products of a world pushing forward, but one without the sophisticated computer technology we have today that gives us more optimal solutions. "But where's the fun in an optimal solution?" I ask myself, listening to yet another F355 exhaust clip.

You Might Also Like