How Eugene’s Urban Forestry program works to protect city trees from erratic weather

An ice storm hailed as one of the worst seen in the Willamette Valley caused power outages, road closures, elicited a county- and state-wide declaration of a state of emergency and downed tens of thousands of trees across the Eugene-Springfield area in mid-January.

But it could have been worse.

Even more trees could have been damaged or broken in the storm had foresters across the area, both employed by cities and supporting volunteer organizations, not worked diligently in prior years to properly prune and maintain trees, minimizing the risk of tree failure.

Power has since been restored, trees are cleared from roadways and temperatures are gradually warming as spring approaches the region. In the aftermath of this most recent winter storm, the city of Eugene’s Urban Forestry program is working to ensure city trees are less vulnerable to erratic weather, including winter freezes and summer droughts.

What is Eugene’s Urban Forestry program?

Eugene’s Urban Forestry program is part of the Parks and Open Space division of the Public Works Department for the city of Eugene. The program promotes a healthier urban environment by managing more than 65,000 street trees within the city, according to Spencer Crawford, the Urban Forestry program supervisor. Street trees are city-owned and occupy space in the right-of-way (ROW) as what Crawford considers an “essential element of the transportation corridor.”

Crawford said the Urban Forestry program is responsible for reviewing plans for street trees, signing contracts for tree installments, maintaining and managing street trees throughout the duration of their lives, removing and replacing trees once they pose a risk to the public and for establishing monetary values for city street trees damaged in events like storms or car accidents that impact a city tree. The program follows an industry standard for trees in the ROW, maintaining them 15 feet over roads and nine feet over sidewalks to allow easy and safe movement underneath tree canopies.

Eugene’s Urban Forestry program adapting to ice storms, drier summers

January’s ice storm damaged or destroyed approximately 1,500 city trees in Eugene, according to the Public Works department’s monthly report. In neighboring Springfield, the impact was worse, with damage to an estimated 20,000 city trees. Springfield was in the process of doing an inventory assessment of the trees it maintains but estimates that there are about 20,000 to 25,000 street trees owned and maintained by the city.

Crawford said shifting climate patterns with lengthening and warmer summers alongside erratic winter storms have led the Urban Forestry program to rethink the types of trees that will be able to thrive in the area in the future. The program is considering changes such as finding cultivars with more drought-resistant trees and seeking out trees in areas such as northern California that may be successful in Oregon in later years.

“There are issues with how what has historically been successful here will continue to be successful here because the climate range is changing so we are asking ourselves ‘what do we need to be successful not just for today but for where this is going to go?’ and we don’t know. It’s a guess but we do know with warmer temperatures, a longer summer season and changes in winter weather patterns like more ice storms, we need to think differently about what trees we put in the urban forest and what trees we think will be successful here because it’s a long game,” Crawford said.

“We’re planting a tree today to be there a hundred years later so we need to be aware and mindful of what it’s going to be in a hundred years for that tree and what it needs to exist.”

While foresters and arborists don’t have a crystal ball to peer into the future with, Crawford said the city’s Urban Foresters use science and years of experience to make responsible decisions for the public. Part of that responsibility includes working proactively to help mitigate trees negatively impacting the public by causing a danger with regular maintenance.

“We’ve had recent ice storms that did a bunch of damage but we got a lot less damage this time around,” Crawford said.

“I think some of that without question can be attributed to how on top of our maintenance program we are for the trees.“

How to know if a tree is owned by the city of Eugene

The Urban Forestry program uses a Geographic Information System (GIS) program to determine whether or not a tree is owned by the city based on location. Additional information includes when the last service of a tree occurred, maintenance history, notes for prior issues and the frequency of monitoring.

Crawford said members of the public often don’t understand that street trees are owned by the city in the same way that traffic signals and parking meters are. While many people understand they cannot remove a stop sign from their corner-lot property or that they should not go out and fill a pothole on a city street themselves, the same idea isn’t always equally extended to city street trees.

“(City street trees are) responsible for the city to maintain. They’re not the responsibility of the public to maintain and similarly so, the public is not allowed to maintain those trees without working through our program to get the permit to do so,” Crawford said.

“Our program is responsible for maintaining the tree, has liability of the tree and has to maintain it in full throughout its life as code dictates.”

Many residents also might not realize how dangerous it can be to maintain or try to remove street trees. To service street trees, urban foresters use boom trucks that raise them to the height of the tree or climbing arborists alongside chainsaws to deliberately prune or deadwood tree limbs.

While discouraging citizens from impacting city street trees, Crawford said the Urban Forestry program is willing to work with home or property owners who wish to remove a city tree near their property to issue proper permits for self-removal if the tree is professionally assessed to cause a significant risk to the public.

What the timeline looks like for planting, maintaining a tree

Young trees require regular watering and maintenance to ensure they can grow strong and provide benefits back to the community for years to come.

When a new development is created, the Urban Forestry program determines the proper tree to place in the right location to optimize its survival. Planting season occurs over winter and for the first summer of a tree’s life, it will be watered on a weekly basis for about four months of summer weather. At year two, the tree is watered every other week. Year three sees watering every three weeks. Crawford said that historically, this watering schedule has been adequate to help trees get a strong start in their new homes. Past 10 years of the tree’s life, the city no longer waters it and the tree is integrated into the Urban Forestry program’s block-by-block tree maintenance schedule for pruning needs.

“The challenge of that is yes, it costs money and time to plant a tree but there’s a lot of follow-up with those trees — the watering regime that’s needed to keep those trees successful and to keep that investment in the ground,” Crawford said.

“That’s actually where at least two-thirds of the cost comes in is the establishment over the procurement of the tree and then the planting of the tree.”

The cost of establishing street trees levels out over time as mature trees take fewer resources to maintain. According to Crawford, as trees mature, the benefits they share increase.

“In order for us to care for the urban forest successfully, we have to make responsible decisions. We have to have an eye toward preservation because the bigger, more mature the tree is, the more it’s giving back to the community,” Crawford said.

“People who have large, healthy trees on their street will live an average of a year longer than those who don’t.”

How trees can benefit the Eugene-Springfield community

From mitigating floods by slowing the rate of rainfall moving into waterways to cooling areas with shade, trees contribute to vibrant, healthy and sustainable communities globally.

Crawford said it can take nearly two decades for a tree to mature to a point where it sequesters carbon, provides intrinsic and holistic value, and reduces runoff captured by allowing greater soil saturation.

“If we remove a tree and replant a tree, that tree is a one-for-one, though it’s not a one-for-one in terms of the benefits it’s giving back to the community — at least not today. It’s going to take time,” Crawford said.

“We give to the tree for about 15 to 20 years and then it starts to give back to us. … That’s why it’s a requirement for us to put the right tree in the right place so that we can get the maximum benefits.”

What is the fiscal value of a mature tree?

Due to the exponential increase of the benefits a tree can provide to a community as it matures, older trees can reach values in the tens of thousands of dollars.

The Urban Forestry program uses information such as how old a tree is, its health and location to determine a fiscal value for trees that need to be removed. Crawford said the program has recently had some trees appraised for upwards of $15,000.

“I think that value can be surprisingly high to people in part because it’s a ton of time and a lot of resources to manage that tree along its life. All of that time — you can’t get the time back and if you have to get a new tree, you can’t get the benefits of a hundred-year-old tree. It’s going to take a hundred years to get those benefits back or at least 20 or 30 before it even gets close to maturity,” Crawford said.

“The value of trees could range from $500 to $25,000 or more but in general, that would be a very highly valuable tree.”

Tree Equity

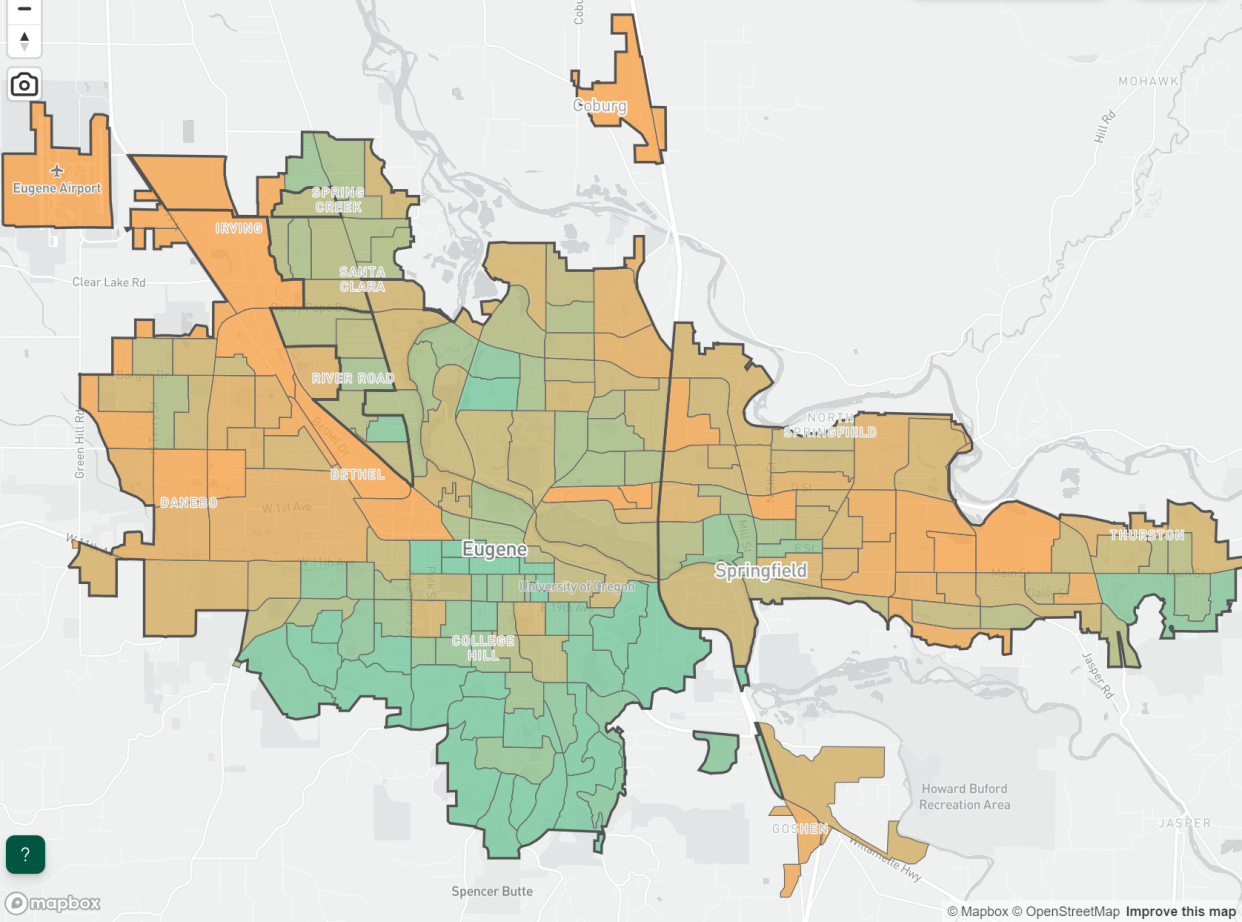

Along with cleaning air, providing necessary shade, uplifting moods and supporting wildlife, the concentration of tree canopy coverage feeds into the concept of tree equity. Eugene tabulates its tree equity score by considering the rate of tree canopy coverage in an area and the relevant surface temperature and how that quantifiable information intersects with employment, income, race and health factors in neighborhoods.

With a composite tree equity score of 85, much of Eugene’s tree canopy is concentrated in the south hills. Areas with lower tree equity scores include parts of west Eugene like the Bethel, Danebo and Irving areas with tree equity scores ranging from around 55 to 65.

Eugene’s city urban foresters use a program called Treeplotter Canopy, which overlays information about tree age, size and other characteristics with census data. This helps correlate percentages of tree canopy coverage with rates of education and income to determine whether or not folks across all statuses in the community are given equal access to green space provided through city street tree canopies.

Crawford said the group of workers in the Urban Forestry program recognize that historically their work has been complaint- or call-based; if somebody reaches out with a need they can support, they’ll provide help.

The program has identified that on average, calls come from people who have the time to call a city program for help and who are likely to have historically older trees. Crawford said when they look at the community of Eugene, those individuals typically live in places like south Eugene with higher-than-average income, higher-than-average employment and have larger trees in the area. Part of the program’s work now includes thinking about how historic practices have led to particular outcomes in the city that don’t necessarily serve everyone equally.

“Being introspective, we say, ‘We’re spending a lot of time in the community giving back to not the whole community but only part of the community,’ though we’re here to service the whole community,” Crawford said.

He said in places like west and north Eugene where the Urban Growth Boundary has most recently expanded and new developments are being established, it is important for the program to consider how ROW trees can have a larger, outsized impact on communities that lack similar access to trees.

“Maybe the only trees in those areas really are the street trees,” Crawford said.

“If that’s the case, how much more important is it for us to have trees of health and size there because they’re not getting the benefits of all of the other private trees?”

“What we’ve done as a team is yes, we’re still going to respond and be responsive to the broken branch that needs to get help. We’re still going to be responsive to that but we’re not just going to do our program only off of responsive work,” he said.

The team continues to work responsively to community needs for the trees they manage but also folds intentionality, forward- and equitable-thinking into their arborist and planning practices.

“We’re going to make intentional planning decisions around where we plant trees and those are going to be in the areas of the highest need and in the areas with the least amount of equity,” Crawford said.

How trees can cause negative side effects

With benefits come costs.

Friends of Trees is a nonprofit organization that coordinates volunteers who plant and care for city trees across the Portland-Metro, Salem and Eugene-Springfield areas. Following the January ice storm, Erik Burke, director of the Eugene-Springfield chapter of Friends of Trees (FOT), went to work helping folks across the area with downed trees.

Burke said that folks who volunteer and work with FOT are “tree people.” Even with a great affinity and appreciation for trees, he said it’s equally important to consider the possible downfalls of planting trees without careful consideration. He said as our weather continues to become more erratic year after year with winter storms and longer summer droughts, it is vital to listen to the very real concerns people have about trees around them.

“I was helping remove trees after the storm from roofs of folks who were really struggling so I think it’s really important to not frame trees as some perfect good but as something that has benefits and costs,“ Burke said.

Burke said some associated costs include the harm that can be done to humans, animals and property from falling trees. Broken branches can knock out power and internet lines, block roadways, and damage infrastructure such as sidewalks and irrigation systems through root growth.

Certain types of trees can also be harborers or attractants of invasive pests that can lead to the decline of an entire population of trees if not handled properly. The 2022 introduction of the invasive Emerald Ash Borer into Oregon prompted a moratorium on the cutting of Oregon ash trees in affected areas.

Experts worry that if the pest’s impact range grows, it could devastate habitats dominated by native Oregon ash trees, like riparian zones and even urban forests. In response, the city of Eugene will no longer approve permits to plant ash trees. Crawford said about 10% of Eugene’s urban canopy consists of ash trees and should the Emerald Ash Borer reach the WIllamette Valley, it has the potential to wipe out about 99% of the native ash tree population.

He said other pests like the Mediterranean Oak Borer can impact oak trees, which are drought-resistant — a trait arborists seek out for trees being planted in Oregon as summers become longer and drier.

‘Wood’ you like to get involved?

While planting and maintaining trees in the ROW should be left to workers in the city’s Urban Forestry program, folks wanting to get involved in tree planting have plenty of opportunities to do so as spring marches on.

FOT is hosting planting events every weekend in March and April that require preregistration for interested individuals looking to wield shovels and plant some saplings. Oregon celebrates Arbor Month in April and with Arbor Day approaching on April 26, there are numerous opportunities to support the community not only by showing up now but by planting resources for future generations to benefit from.

Trees are typically planted in the winter. This year’s planting is likely to be reduced due to time lost to storm responses but the old adage remains true: “The best time to plant a tree was 20 years ago. The second best time to plant a tree is now.”

Hannarose McGuinness is The Register-Guard’s growth and development reporter. Contact her at 541-844-9859 or hmcguinness@registerguard.com

This article originally appeared on Register-Guard: Eugene foresters work to protect trees from erratic weather