EPA reviewing much-criticized water pollution rules for industrial-sized CAFO farms

The EPA is studying pollution from industrial-sized animal farms, potentially a first step toward new rules that could impact North Carolina’s booming hog and poultry industries.

As part of regularly updating water pollution rules, the federal agency will consider whether animal facility rules adequately protect public waterways. The move stems from a 2021 lawsuit filed by Food & Water Watch, a non-profit watchdog organization.

“There have been regulations on the book for over 15 years that have really failed to solve the problem of factory farm water pollution and the impact it has on waterways and communities,” Emily Miller, a Food & Water Watch staff attorney, told The News & Observer.

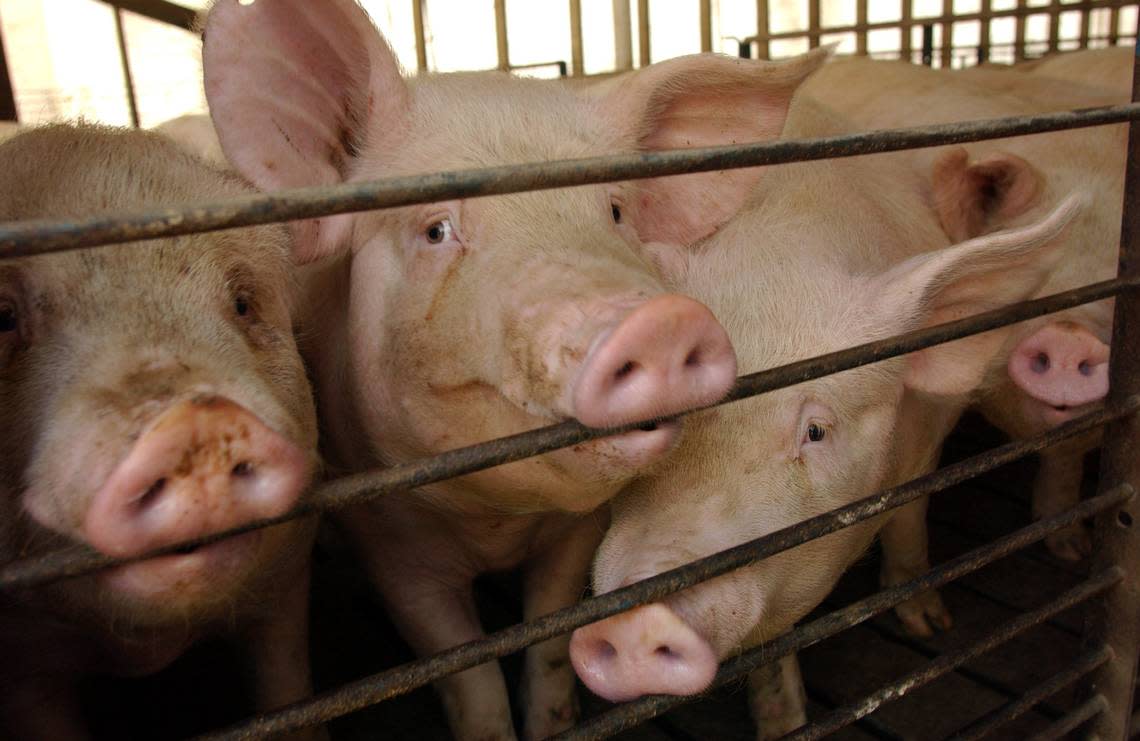

Poultry and hog growers raise as much as tens of thousands of animals in barns, some of them stretching as long as two football fields. The animals produces lots of waste, which is often disposed of by getting spread on farm fields as fertilizer.

Existing federal rules bar farms from discharging poultry litter, hog manure or wastewater into nearby waterways. But there’s two key exceptions: If waste runs off during a rainstorm from fields where it’s been sprayed or spread, it’s deemed “agricultural stormwater.” And pollution is allowed to spill from animal houses, lagoons or storage areas during heavy rains as long as the facility has been designed to withstand a 25-year storm during a 24-hour period.

Those exceptions frustrate environmental advocates, who have long called for the EPA to change its rules, which were last updated in 2008.

When the EPA last updated its effluent limitation guidelines, it opted not to review industrial animal farms based on data from 18 facilities.

That decision, Miller said, doesn’t reflect the reality of pollution from industrial farms. There are more than 20,000 CAFOs, or concentrated animal feeding operations, in this country. The EPA defines CAFOs as a lot or feeding operation where animals have been kept for at least 45 days over the last year without vegetation in the confinement during the growing season.

Animal manure includes nitrogen and phosphorus, nutrients that spur algal growth when washed into waterways. Algae decreases oxygen levels, which can be harmful to fish and other aquatic life. Toxic algal blooms can be harmful to people and animals.

“We understand that we’re seeing contaminants and pollution that is basically falling through the cracks,” EPA Administrator Michael Regan recently told The News & Observer.

As part of Effluent Guidelines Program Plan 15, the agency will seek out the most up-to-date science to inform regulations, Regan said.

“I don’t know if it’s more so the science is changing or that we are actually now wanting to pay attention to what the science has been saying,” he said.

Changing times, changing needs

Critics like Miller say the EPA has used outdated data when it comes to regulating CAFOs.

For instance, one of the exemptions allows pollution to go unregulated if it washes into a waterway during a “25-year, 24-hour” rainfall event, or storm that has a 1-in-25 chance of happening in a given year.

But the EPA uses information from 1961 to determine what it considers a 25-year storm. Critics say that outdated measure underestimates the intensity of storms today. And as a result, it underestimates the amount of animal waste washed into creeks and streams, as well as the amounts of rain that lagoons should be built to withstand.

“That’s clearly not reflective of the current reality, the reality we are in where we have increasingly harmful weather events and flooding,” Miller said.

Industry officials say they want to keep the status quo.

N.C. Pork Council CEO Roy Lee Lindsey called the EPA study an “extremely costly and lengthy process” in a written statement, arguing it will take at least two years followed by potential rule-making that could take additional years.

“We believe the current guidelines are working as intended. Discharges from swine facilities are rare,” Lindsey wrote.

Any changes to rules impacting manure management would need to be both achievable and affordable, according to the EPA’s plan. The hog industry’s current method of storing waste in open lagoons and spraying it on nearby fields is the most effective way to handle waste, Lindsey argued.

Evaluating what tools are available to manage waste and whether they are considered affordable will be part of the study, the agency wrote in its plan.

Regulators also plan to study if pollution from animal facilities is concentrated in certain states or regions.

Nationally, North Carolina ranks second for turkey production, third for hogs and fourth for chickens. Each year, the state raises more than a billion combined chickens and turkeys, with the industry poised to continue growing.

Hog and poultry CAFOs are often clustered near each other in the North Carolina’s Coastal Plain.

Tributaries from Bladen, Duplin and Sampson counties wash into the Cape Fear River as it wends to the coast. Those counties have dense clusters of hog, chicken and turkey barns.

Adequately estimating how pollution barns, lagoons, exhaust fans and other farm components impact water quality in the region is vital, said Cape Fear Riverkeeper Kemp Burdette.

That work, Burdette said, “applies to the Cape Fear Basin more than it applies to any other basin on Planet Earth — for swine. There are more hog farms here than anywhere.”

This story was produced with financial support from 1Earth Fund, in partnership with Journalism Funding Partners, as part of an independent journalism fellowship program. The N&O maintains full editorial control of the work.